Danelle Hackett wanted her Marine husband to focus on the lives he saved disarming IEDs as a military bomb technician during two tours in Iraq.

Maj. Jeff Hackett could only focus on his 16 colleagues who died during the dangerous bomb disposal missions he led from early 2005 through late 2007.

"My husband looked at those guys as his own family, his own sons. Repeatedly losing techs just wore on him and wore him. He blamed himself for every death," Danelle Hackett said.

In June 2010, after a day of drinking at an American Legion Post in Wyoming near the family's home, Jeff Hackett downed a couple more swigs of alcohol, said "cheers" and shot and killed himself.

Among the highly skilled and elite ranks of military explosive ordnance disposal technicians — the men and women who have been on the front line of the war on terror since Sept. 11, 2001 — suicide is a growing concern.

"It is literally an epidemic," said Ken Falke, a former EOD technician and founder of the Niceville-based EOD Warrior Foundation, which supports current and former military EOD techs and their families.

EOD technician Maj. Jeff Hackett, right, on deployment. Although he saved many lives, Hackett had issues dealing with the death of 16 colleagues and committed suicide June 2010.

Photo Credit: via the (Pensacola, Fla.) News Journal

EOD technicians from all branches of the military graduate from the Navy's Explosive Ordnance Disposal School at Eglin Air Force Base. The school holds a moving memorial every spring and adds the names of graduates killed in combat during the previous year to its memorial wall. Since 9/11, 131 EOD technicians have died in combat and another 250 have sustained major physical injuries including lost eyesight, lost limbs, paralysis and major burns, but it is the numbers that aren't tallied that are now most alarming to Falke and many others.

Suicide is a major concern throughout the military and it is a special concern for the EOD Warrior Foundation, said Nicole Motsek, the foundation's director.

"We are a small community; we have only 7,000 people on active duty. During some months, it has been every week that we have lost someone. There are so many people out there with the invisible wounds of war and they are a part of our EOD community. We cannot wait and hope they get help, we have to do something now to help them," said Motsek, who is married to an Army EOD technician who has had multiple combat deployments.

The foundation plans a round-table summit in November to discuss suicide among EOD techs. The foundation is also holding a retreat this fall for "White Star widows," the widows of EOD techs who have killed themselves.

The foundation does not have an exact number of EOD techs who have taken their own lives, in part because it is often difficult to tell if someone died accidentally or intentionally and also because there is not a good national tracking system. According to the latest information from the Veterans Administration, 20 veterans take their own lives each day, but that number only includes full reporting from 20 states.

EOD tech Air Force Sgt. Chris Ferrell has attempted suicide four times. He has a sleeve of tattoos on his arm with 26 stars, each one represents a friend he lost on the battlefield.

Photo Credit: via the (Pensacola, Fla.) News Journal

Air Force Sgt. Chris Ferrell, a 32-year-old EOD tech who has had many combat deployments to both Iraq and Afghanistan over the last 13 years, has attempted suicide four times.

He has a sleeve of tattoos on his arm with 26 shaded-in stars, each one represents a friend he has lost on the battlefield.

"Every one of them were killed by IEDs," he said. "For every IED you disarm, you save between one and 10 lives, but there is always another one you cannot take care of that gets hit. There becomes a point where it haunts your nightmares and it haunts your thoughts during the day."

A breaking point involved losing a good friend, Air Force Sgt. Anthony Campbell Jr., to an explosion in Afghanistan in 2009.

Ferrell was just five feet away from Campbell when the blast went off.

"You can armchair quarterback that situation all day long, it is something that will never go away for me," he said.

In 2014, on the fifth anniversary of Campbell's death, it all became too much.

"It all just ran over me. I tried to drive my vehicle into a tree because I didn't feel like I had earned the right to stay on this earth," he said.

Ferrell tried getting help, but nothing seemed to work.

"Every time I started to feel like I was getting on the right road, I would always go back to this Rolodex of images of prior incidents — always something that had actually happened. It eventually overwhelms you," he said.

Air Force Sgt. Chris Ferrell has been deployed to both Iraq and Afghanistan many times over the last 13 years. He was just five feet away from his good friend, Sgt. Anthony Campbell Jr., when he was killed by an explosion.

Photo Credit: via the (Pensacola, Fla.) News Journal

Ferrell went for in-patient treatment at a military hospital where experts talked with him about his suicidal thoughts, but he said it was the thought of his three young children that motivated him to move forward.

"You have to find a purpose and new life," he said.

He now advises senior Air Force leadership about suicide prevention and awareness.

"There is a stigma about suicide, but we are getting better about making it more known," Ferrell said. "For the ones out there who are struggling (with suicidal thoughts) my message to them it is that you are definitively not alone, it does not have to be all on your shoulders."

Danelle Hackett didn't know what to do to help her husband when he returned from his combat tours.

"I could tell he was mess," she said.

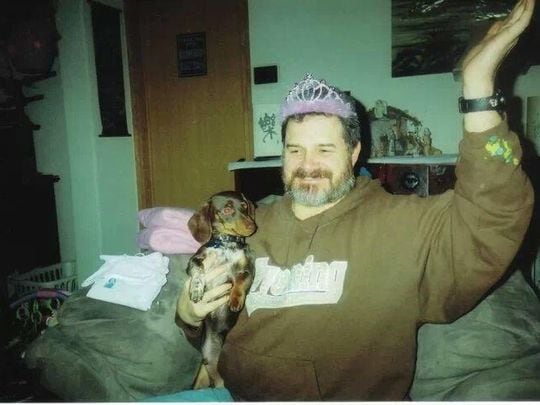

Maj. Jeff Hackett entertains his young granddaughter during the Christmas holidays. Hackett's wife, Danelle, says he lost the laughter that he had always had after returning from his combat tours.

Photo Credit: via the (Pensacola, Fla.) News Journal

Jeff Hackett began drinking heavily and getting into petty fights with his sons.

"He lost that laughter that he had always had. He was always such a funny guy and I was usually the butt of his jokes," said Hackett, who recalled her husband dancing around and laughing to the 1992 song "I'm Too Sexy."

During his first deployment to Iraq, he began sending his wife emails saying that he could no longer stand to look at himself. When he came home on leave he lost interest in things he once enjoyed like gardening and NASCAR.

"He wouldn't sleep for days. When I would get up in the mornings, I honestly never knew who I would be waking up to. We would tell him that he needed to go and talk to somebody and he would tell us that he didn't have problem, that we were the ones who had the problem," she said.

"He got really hateful at times with his words. He would drink the biggest bottle of Makers Mark in two days and he would act out in front of his family, he would berate the kids."

Danelle Hackett knew something was terribly wrong, but she didn't know what to do to help her husband. She said the military's policies made things worse because Jeff Hackett worried that if he sought treatment he would be pulled from duty and couldn't continue his vital work.

And Jeff Hackett could never let go of the deep sense of failure he felt about the people he could not save.

"He felt like he was bad for the (EOD) field, like he had messed up and let the field down because he wasn't able to bring home the ones who were killed. He felt that he was a huge let down to their families and the guys he lost. He felt like he was a failure no matter how hard I tried to tell him otherwise."

Four years after her husband's suicide, the couple's 24-year-old son, Drew, killed himself. Drew Hackett had been deeply troubled by his father's death, she said.

By speaking out about the deaths of her husband and her son, Danelle Hackett hopes to make a difference for another family.

Other EOD suicide deaths include a Navy captain and an Army colonel and other sailors, soldiers and airmen of all ranks and backgrounds, Falke said.

Part of the problem in addressing the issue is that EOD techs come from all branches of the military and often work with small special forces units — Ferrell and Campbell were deployed with a British special forces unit when Campbell was killed. The EOD techs train at the same school, but techs from the four military branches work independently and in small groups, he said.

The foundation's goal is to bring the entire EOD community together to focus attention on the issue.

Maj. Jeff Hackett holds his newborn granddaughter.

Photo Credit: Danelle Hackett/Special to the (Pensacola, Fla.) News Journal

"Our real problem right now is within the veteran community, but we also want leadership in active duty to know that during transition to civilian status, they have to do more than teach people how to write a resume. They need to know that civilian life is different," Falke said.

Another problem is that service members today are often treated by the general public as either revered heroes or they are pitied.

"I would hope that people will ultimately put them in the middle of those extremes, which would be respect," Falke said. "When you are in the military, you get this super hero status. When you come back home, you can lose your sense of mission and purpose and start to feel really sorry for yourself."

Ferrell agreed.

"You are put on a pedestal or you are pitied and there is no happy medium — it's either 'you did this and you did that and you are amazing', or 'I am going to help you, what can I do to help you'."

The best thing people can do is just listen, Ferrell said.

"Talk to the veterans, learn their stories. Sit down and have a conversation with them just so they can let it out."

For information about the EOD Warrior Foundation and the memorial wall, visit www.eodwarriorfoundation.org/

Explosive Ordnance Disposal technicians assigned to the 466th Air Expeditionary Squadron, walk toward a blast pit after detonating four 500-pound bombs during demolition day, March 16, 2014.

Photo Credit: Staff Sgt. Vernon Young Jr./Air Force