The top American commander in Afghanistan, Gen. John Nicholson, heads to Capitol Hill on Thursday where he is likely to endure intense questioning from Senate lawmakers who've grown weary of the endless military mission there. There's a long list of reasons why the United States can't yet extract from its longest war, and chief among them is the competency of Afghanistan's air force, which according to the United Nations' latest assessment is responsible for a troubling pattern of botched airstrikes that have led to a stunning rise in civilian casualties.

Compared to 2015, last year the loss of innocent life caused by Afghan-initiated airstrikes doubled to 252, according to the U.N. That figure includes civilians killed and wounded. And while American military officials allege those numbers are grossly inflated, they have nevertheless begun to fast-track training for a new cadre of Afghan tactical air controllers who, from the ground, can warn pilots when they are at risk of causing collateral damage.

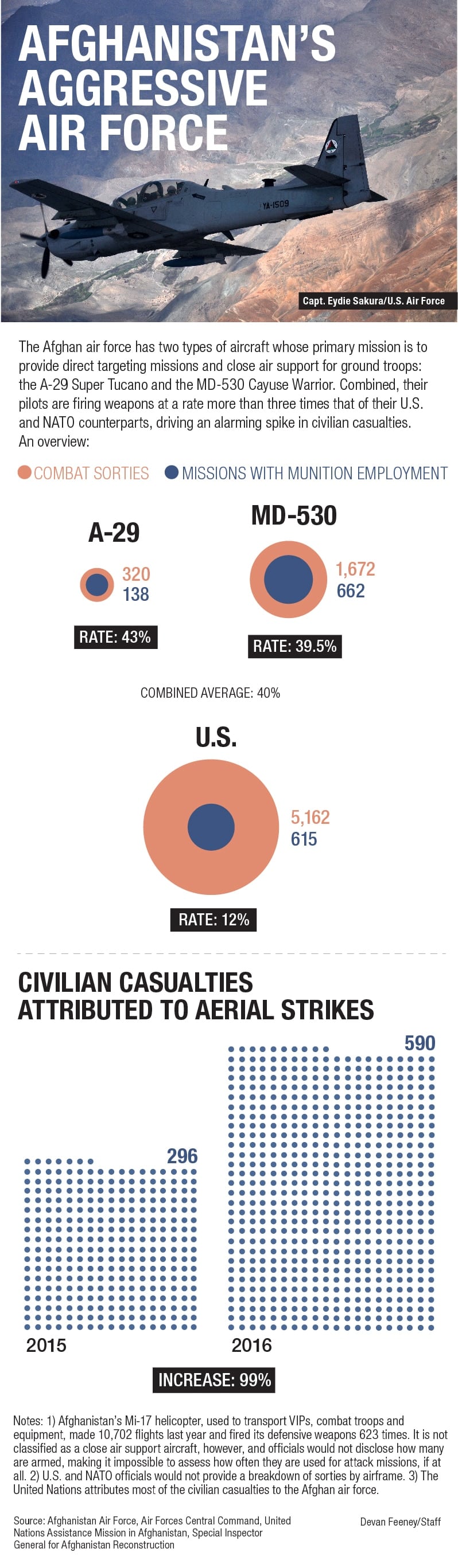

Here's what the numbers say: Afghanistan's primary attack pilots are firing their weapons during four of every 10 combat missions, a rate more than three times greater than that of their U.S. Air Force counterparts, according to a Military Times analysis of figures provided by American and Afghan defense officials. What remains an issue of debate is whether the surge in civilian casualties is to blame on the Afghans being overly aggressive or undisciplined, whether it's a symptom of the hasty training necessitated by their rapid growth, or whether it's just the inevitable result of assuming greater responsibility for their country's security.

Regardless, it's an enormous predicament, not only for Nicholson, but for President Donald Trump and his administration. The U.S. military's ability to leave Afghanistan is inextricably linked to the success of Afghanistan's security forces — and most especially its air force, which is seen as a vital link to protecting Afghan ground forces from the pressure they face from relentless Taliban militants and the host of al-Qaida affiliates operating throughout the country.

"Whenever U.S. officials talk about the various incapacities of the Afghan military, air cover is always at the top of the list," said Michael Kugelman, an Afghanistan expert at the Woodrow Wilson Center, a Washington think tank. "... The Taliban's growing momentum on the battlefield and its increasingly deadly impact on civilians can no longer simply be shrugged off. Afghanistan needs to do things to bring it under control, and scaling up the capacities of a troubled air force is a modest albeit important step forward."

Today, of Afghanistan’s 407 districts, 133 are considered to be contested and 41 are under full Taliban control, according to the U.S. Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction. About 8,400 U.S. troops remain deployed there as part of Operation Resolute Support and a smaller counter-terrorism mission called Operation Freedom's Sentinel. It's unclear what Trump's intentions are, though reports suggestthat in December he told Afghan President Ashraf Ghani he would be open to sending more U.S. forces back to the region. It's unknown what role they might play, though.

U.S. military officials insist Afghanistan's combat pilots exhibit restraint while in the cockpit, saying 66 percent of their requests to attack specific targets are rejected over concerns they could result in unintentional deaths. But further conditioning remains a priority.

In 2016, Afghan pilots operating their country's two primary attack aircraft — the fixed-wing A-29 Super Tucano and the MD-530 Cayuse Warrior, a small but potent attack helicopter — flew 1,992 sorties and conducted 800 airstrikes, according to data provided to Military Times by Afghanistan's air force. By comparison, U.S. Air Force combat aircrews flew 5,162 such missions during that period and conducted 615 strikes, according to American officials in Kabul and open-source data maintained stateside.

That's a 40 percent attack rate for the Afghans compared with 12 percent for their American counterparts.

Afghan Air Force MD-530F Cayuse Warrior helicopter fires its two FN M3P .50 Cal machine guns during a media demonstration, April 9, 2015, at a training range outside of Kabul, Afghanistan. (U.S. Air Force Photo by Staff Sgt. Perry Aston)

Photo Credit: U.S. Air Force Photo by Staff Sgt. Perry Aston

There are some caveats, however, U.S. officials say.

As a Military Times investigationrevealed this week, last year the U.S. Army conducted 456 airstrikes in Afghanistan from armed attack helicopters and drones, previously undisclosed figures that have raised significant questions about the U.S. military's broader transparency in reporting its activity not only in Afghanistan, but in Syria and Iraq — and potentially as far back as 2001, when the war on terrorism began.

U.S. officials in Kabul provided the Army's statistics to Military Times to illustrate that Afghan pilots, when compared with the Americans, are not trigger happy. However, officials could not provide the number of sorties conducted by Army helicopters and drones, thus making it impossible to calculate overall how frequently American pilots are firing weapons and dropping bombs.

U.S. Central Command, which oversees the wars in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria, was unable to readily provide Military Times with that data, either.

There are distinctions, too, in how each side defines its combat missions, U.S. officials argue. The Afghans' A-29 primarily attacks pre-selected targets, including heavy weapons, tactical vehicles, massed forces, and individual terrorist leaders and Taliban commanders. The Afghans refer to this as a "close air attack." The MD-530 provides real-time air support to ground troops engaged in battle, as do U.S. aircraft.

This is noteworthy because the A-29, which joined the Afghans' fleet only last year, currently lacks the sophisticated communications equipment to make it truly effective in a close-air-support role. In fact, the aircraft can radio their operations center only within a 14-mile radius, U.S. officials said.

The Afghan air force fields three Mi-35s as well, aging helicopter gunships nearing the end of their service lives. They are armed with a Gatling gun and 57mm rockets. However, they seldom fly due to a lack of spare parts. Also, the Mi-35 and its pilots are not trained or advised by Americans. The U.N. says Mi-35s were responsible for seven civilian casualties last year.

Of the 252 civilian casualties blamed on the Afghan air force, 85 resulted in death. The U.N. attributes most — 224 — to strikes by helicopters. The A-29 caused 24.

Air Force Capt. Jason Smith, a spokesman for the U.S.-led training mission, told Military Times he’s aware of only two incidents last year in which an Afghan A-29 or MD-530 killed civilians.

By comparison, the U.N. blamed 235 civilian casualties — 127 deaths — on airstrikes carried out by the U.S. and its international partners. The high toll is "largely attributable" to one controversial operation in Kunduz province in which 60 Afghans were either killed or injured.

A member of the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces participates in air-to-ground integration training in Kabul province, Afghanistan, Dec. 27. The integration of air to ground training with live fire assets enables ANDSF operations and capabilities. (Photo by Air Force Capt. Kay M. Nissen)

Photo Credit: Air Force Capt. Kay M. Nissen

Expect Nicholson to vigorously defend the Afghans and the training they’re being provided. U.S. officials say these pilots continue to make gains in their capability, proficiency and use of restraint. Air Force Brig. Gen. David Hicks, commander of the 438th Air Expeditionary Wing, said that "on more than one occasion, A-29 pilots have come back from missions without dropping their munitions." Hicks, who heads the coalition's train, advise and assist mission for Afghanistan’s air force, also noted "the reasons for not using weapons are very telling. I hear things like, 'civilian considerations, inability to discern targets and unexpected friendly forces.' "

Afghan pilots are held accountable for any civilian casualties they may cause, said Air Force Col. Sean McLay, senior U.S. adviser to the Afghan air force. In about 12 percent of the Afghans’ missions, he added, pilots return without striking their predetermined targets.

Last summer, NATO and U.S. forces introduced a program to train Afghan tactical air controllers who guide pilots to their targets. The training lasts about four weeks and includes instruction on relevant equipment, map-reading, communications and the specific skills required to talk an aircraft onto a target.

To date, the program has graduated 30 students, with ongoing courses in Helmand and Logar provinces. By the start of the next fighting season, in April, officials anticipate there will be more than 40 Afghan tactical air controllers qualified to coordinate airstrikes.

"Their role in increasing accuracy and decreasing collateral damage can't be understated," said Lt. Col. Andy Janssen, who heads the program. "We were briefed recently that an [air controller on the ground] called off an attack because a couple of goat herders came too close to the target that was to be engaged. Feedback like that verifies the success of this program."

Shawn Snow edits Military Times' Early Bird Brief. On Twitter: @snowsox184.

Andrew deGrandpre is Military Times' senior editor and Pentagon bureau chief. On Twitter:

.

Shawn Snow is the senior reporter for Marine Corps Times and a Marine Corps veteran.