They had come from the nation’s capital, the beaches of Key West, the streets of Philadelphia and beyond.

They boarded buses and trains, where white drivers sent them to the back. Careful with their first steps away from home, they complied. They headed into a new world, built in the snake-infested woods of Montford Point Camp, North Carolina.

The first of their kind 75 years ago, they emerged from those woods and into storied Marine battles on Pacific Islands and into the Pentagon’s corridors of power.

Through their trials, they built a foundation on which future generations of black Marines would stand.

On Aug. 26, 1942, the earliest recruits of the first segregated basic training in the Corps arrived — their first task was to clear out trees and build wooden barracks.

Recruits marched over bear tracks, stomping out a place of their own as the Marine Corps begrudgingly opened its ranks to blacks for the first time.

Only a year before, then-Commandant Maj. Gen. Thomas Holcomb told leaders in Washington that taking “Negroes” would be a “definite loss of efficiency.”

“If it were a question of having a Marine Corps of 5,000 whites or 250,000 Negroes, I would rather have the whites,” Holcomb said.

But Holcomb had little sway when President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued executive order 8802, which prohibited racial discrimination in the services.

At the time, three eventual Montford Point Marines didn’t know that their future commandant didn’t want them. All they knew was the Marines were accepting blacks and they wanted in.

They would be in the first wave of the nearly eight years of Montford Point’s existence, which produced nearly 20,000 black Marines and closed permanently in 1949 when the armed forces integrated.

Numbers would hover between 1-3 percent until the end of the Korean War. Today, black Marines make up 10 percent of the Corps.

The early few

Charles Manuel Jr. grew up in the shadow of the Key West (Florida) Naval Station, where he watched sharp-dressed Marines marching in formation. When the war broke out he was in high school, and a Marine recruiter came calling.

He was from the South — sitting in the back of a coloreds-only train car wasn’t as daunting as it was for his fellow recruits. But cold nights in tents during basic training had him missing home.

Joseph Carpenter was raised in Washington, D.C., and often went to the movies as a child. It was on the black and white screen that he and his friends first saw Marines. The World War I-based films showed jarheads fighting on the battlefield or slugging it out in bar fights.

“That impressed us,” Carpenter said.

It wouldn’t be until he graduated high school and worked as an apprentice in the D.C. Navy Yard when he learned he could join too.

He’d be one of the first recruits in the camp’s second year, when Marine legend and later Sgt. Maj. Gilbert “Hashmark” Johnson led recruit training and black drill instructors replaced whites.

Ivor Griffin went with his buddies to sign up for selective service. Many waited months to find out if they would be called.

Griffin had four weeks.

The official lined the three up, told the first he was headed to the Army and the next he was headed to the Navy.

He pointed at Griffin: “You’re in the Marine Corps.”

Before Griffin left, his stepfather warned, “Watch yourself, they’re known to hang black men down there.”

Montford Point Marines, though fewer in number than Army and Navy counterparts, played an outsized role in the acceptance of blacks in the military, said Robert Jefferson Jr., a history professor at the University of New Mexico.

In many ways, Jefferson said, black Marines got little recognition for their sacrifice, despite having proven themselves in bloody Pacific island battles. Some military leaders pointed to that service to later support future integration.

Blacks had served in various capacities since the Revolutionary War. Entire units had fought in the Civil War and World War I. Despite these contributions, Jefferson said many isolated black communities away from military posts knew little about black military exploits.

It took political pressure from black leaders in the NAACP and other organizations for Roosevelt to issue 8802 at all, Jefferson said. And even that order was restricted.

Quotas allowed no more than 10 percent black troops per unit, though numbers would never reaach that level during the war. And assignments kept most black troops in noncombat jobs such as cook, supply or steward.

During World War II, black units received scant coverage in the major news outlets. But they were followed closely by the black press.

Much of the coverage focused on the good job the Marines were doing overseas but didn’t mention the discrimination or other problems minorities faced. The horrors of war were rarely reported either. Both angered many blacks, Jefferson said.

Most of the men serving in those first waves of a segregated Marine Corps didn’t note the history at the time, despite its later significance.

“Little did they realize they were setting a trend, a standard of excellence that the Marine Corps would embrace in the years to come,” Jefferson said.

A hard reception

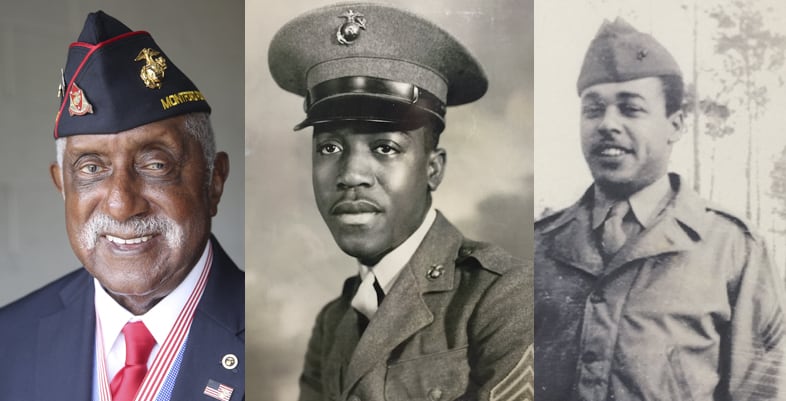

Griffin, Manuel and Carpenter, now in their 90s, shared much of the same experiences. As they arrived in North Carolina, they confronted segregated transportation, restaurants and bathrooms.

They knew there were places they couldn’t go when they left the camp.

The men recalled downtown Jacksonville, North Carolina, a village of less than 1,200, had perhaps three square blocks and was divided by railroad tracks. On one side were the white townspeople. On the other were a handful black families.

Today, more than 67,000 people live in Jacksonville and 20 percent of them are black, according to Census data.

In December 1942, nearly four months after the boot camp opened, the men got their first liberty and headed into town to celebrate and catch a ride to the nearest cities. Town merchants, startled by the sight of a hundred black Marines in green, shut their stores, the bus and train station.

The camp commander called in military trucks to take the Marines where they needed to go.

Griffin, Carpenter and Manuel said they mostly bypassed white establishments, looking for juke joints run by black owners and getting meals from side windows or backdoors of restaurants, as was the rule at the time. But they couldn’t avoid colliding with fellow Marines.

White Marines barred blacks from leaving Montford Point on one occasion, Carpenter recalled. So, those who’d been blocked at the gate went back, rounded up fellow black Marines, who took off their black leather, brass buckle belts and left the camp. Rolling brawls erupted.

But soon, Carpenter said attitudes among some white Marines stationed on nearby Camp Lejeune, changed.

Carpenter was returning from leave and fell asleep in the white section. When the bus driver stopped and told him to get off, white Marines came to his defense, telling the driver to shut up and keep driving.

When this happened to some of his friends, both white and black Marines would kick the driver from his own bus and drive it back to the gate themselves.

The first year the training cadre, commanders and support staff were white. But quickly Marine leaders identified promising new recruits and made them into “acting Jacks” to serve as drill instructors.

One of Griffin’s drill instructors was a private. Despite his rank, or perhaps because of it, he drove the recruits hard. The black drill instructors were tougher on them than the whites, because they wanted the recruits to be tested.

A heritage remains

Some of the Marines who are now charged with keeping the history and significance of Montford Point alive had little to no knowledge of its existence when they were in uniform.

Montford Point Marine Association President Forest Spencer Jr. admitted he was a little embarrassed to not learn of the history until shortly before he retired.

“Not a lot of information was passed on to active-duty Marines,” Spencer said.

Much of that changed when former Commandant Gen. James Amos pushed for greater recognition of Montford Point Marines and black Marine history.

Everett Wills, a retired gunnery sergeant and association member, enlisted in 1976. Even then, nearly 35 years after Montford Point opened, Wills said there were few blacks serving as officers or in the senior enlisted ranks.

Only a few years before, in the late 1960s, large-scale riots and race-charged brawls between white and black Marines had led to stabbings, beatings and deaths at Lejeune, Okinawa and in Vietnam.

In 1968, Headquarters Marine Corps began compiling briefs on race-related incidents in the Corps. The 2nd Marine Division commanding general created a committee to address the issue.

Through the years much of the tension subsided as blacks attained higher ranks, including generals and sergeants major of the Marine Corps.

Spencer said honoring the past, even if it was segregated, can help people appreciate the present.

“Segregation is over, all Marines are forged through Parris Island, San Diego or Quantico,” Spencer said. “Now my objective is to quench this thirst of knowledge.”

With that, Wills and others are leading a multiyear research project to find all the names of each of the nearly 20,000 Marines trained at Montford Point. Many records were damaged or lost.

Manuel would reach the rank of staff sergeant. He loved the Corps, but left after he started a family. Carpenter rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel, helping modernize the Corps by installing one of the first mainframe computers.

Griffin left the Marines briefly after the war and his service in the Pacific but returned and later fought in the Korean War and served aboard ships in the blockade of Cuba during the Cuban missile crisis.

Each of the three count their years in uniform as some of their most cherished, but they reflect on it in different ways.

Griffin admits he faced a lot of discrimination both in and out of the Corps. He harbored resentment for many years. But in his ninth decade, that has dissipated.

“This is a new era — that’s all done now,” Griffin said. “I’m a full man now. I’m now whole and I don’t hold prejudices against anyone.”

Long gone but not forgotten is “Hashmark” Johnson, one of the first black drill instructors to oversee training.

He garnered the nickname “Hashmark” because he had more service stripes, or hash marks, than chevrons.

In 1974, two years after his death from a heart attack while speaking to Montford Point veterans at Camp Lejuene, Montford Point Camp was renamed Camp Gilbert H. Johnson.

Before his passing, the hard-nosed former drill instructor reflected on what his men accomplished.

“As I look into your faces tonight, I remember the youthful, and sometimes pained expressions at something I may have said … But I remember something you did. You measured up, by a slim margin perhaps, but measure up you did. You achieved your goal. That realization creates within me a warm appreciation of you and a deep sense of personal gratitude.”

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.