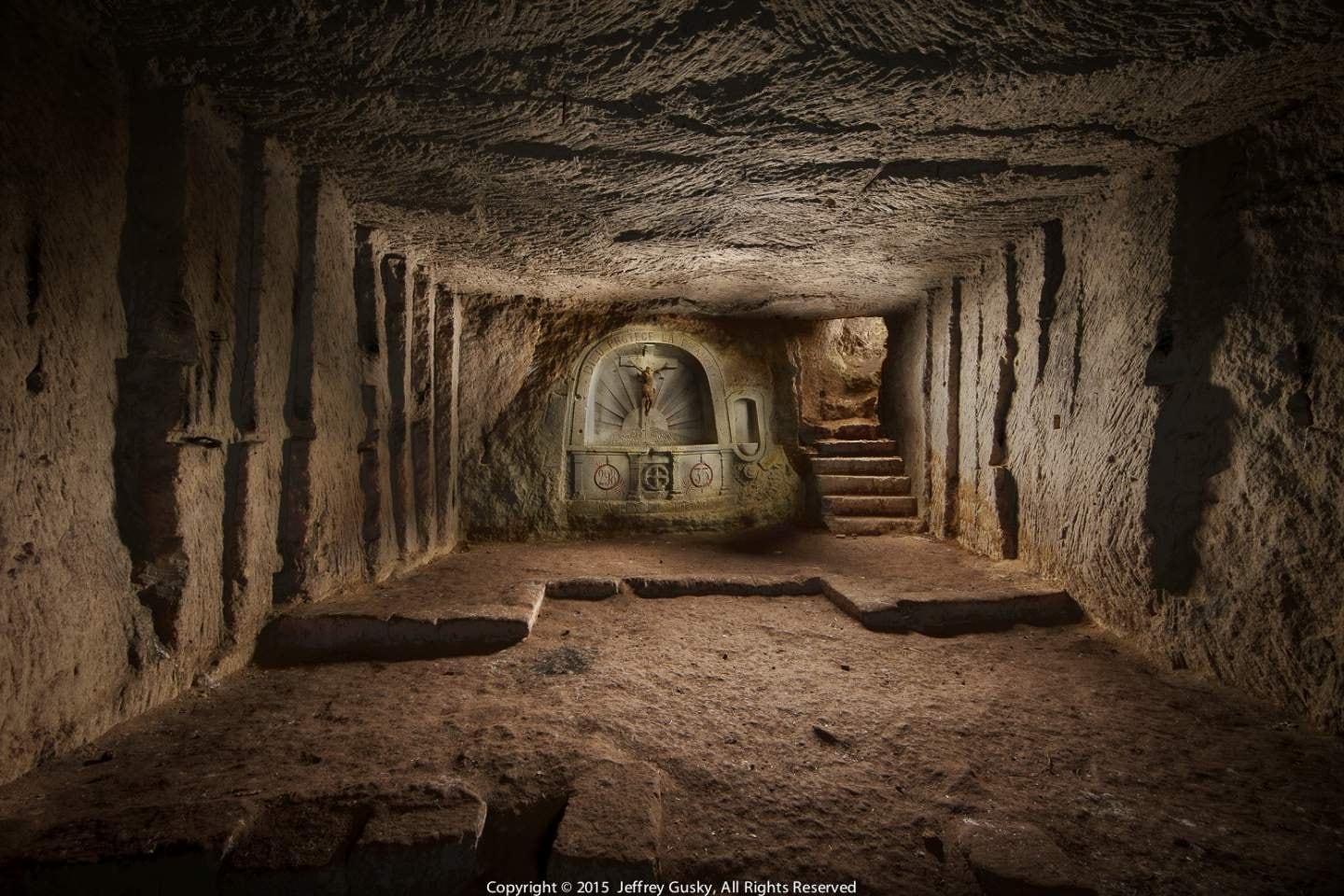

In underground quarries, spanning for miles underneath the surface of the quiet French countryside, abandoned, make-shift cities hold touching remnants of World War I.

Sleeping quarters, places of worship, even tables still littered with mess kits, are hidden 50 feet underground, unknown to many people and even historians.

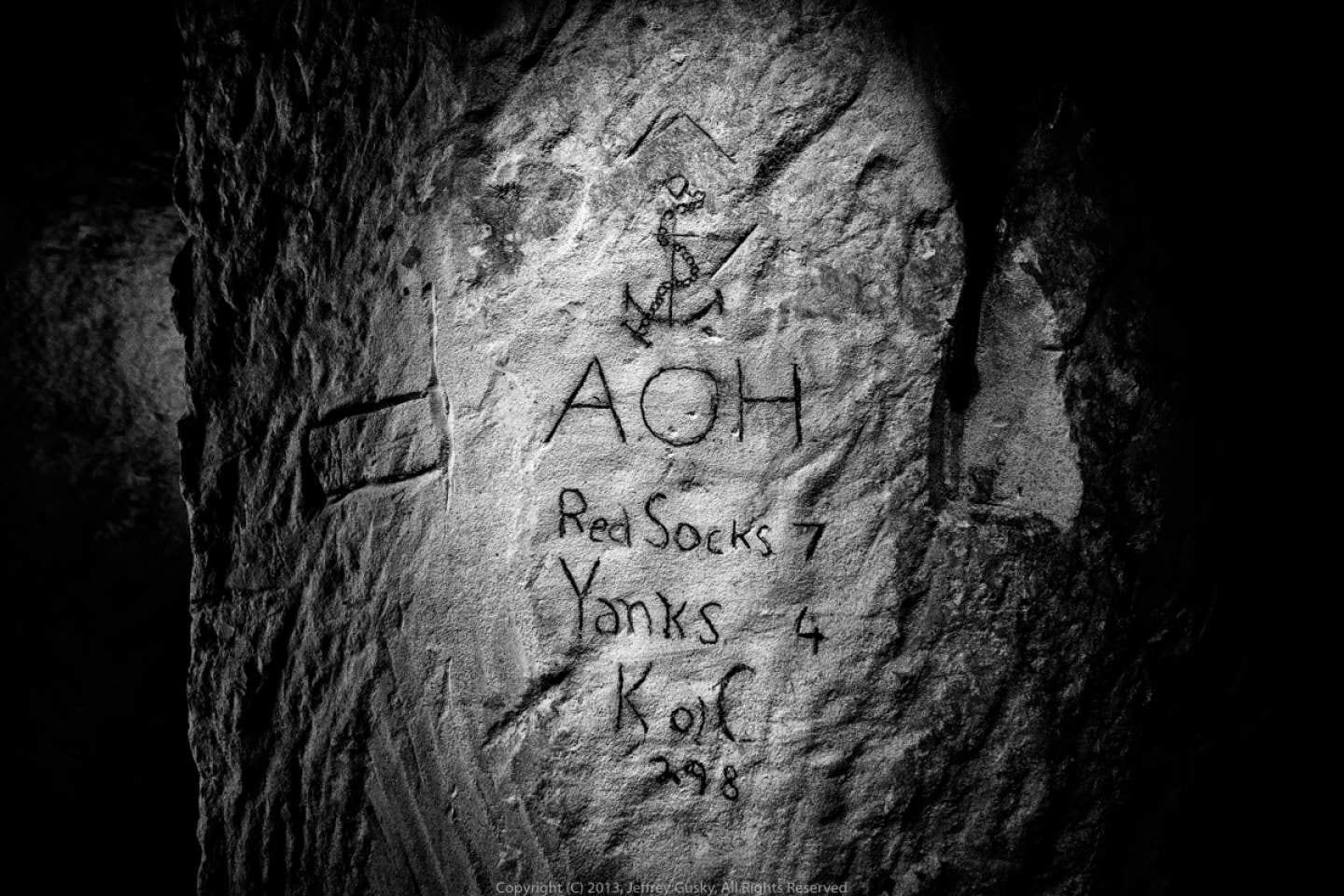

Accompanying these artifacts are drawings, carved into the walls of these cavernous quarries, signatures of the individuals, on both sides of the fight, who came together to serve in the war.

“They created a human world with artwork, with a lot of messages to the future, and jokes and notes to loved ones,” said Jeff Gusky, an artist and physician who explored these cities in 2012. “They recreated, the best they could, a human world underground when the surface of the earth became inhuman.”

When Gusky first saw the carvings, he was awed by the humanity and the humanness that can be found within them, even though their creators were in the midst of fighting a war to change all wars.

His photographs make up half of a current art exhibit at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, titled “Artist Soldiers: Artistic Expression in the First World War.” Artist Soldiers is the centerpiece of the museum’s four-year observation of WWI.

“WWI gives us a language to see ourselves, and how, if we lose humanness we are finished,” said Gusky.

The underground cities they dwelled in have remained relatively untouched for the past hundred years, known only to the local French people living in the area. They would like to keep them that way, according to Gusky, but he is sharing his photography of the carvings because of their relevance to modern day.

The war marked massive change around the world. It introduced society to new technologies both helpful and harmful, that modernized cities and carried an enormous cost of life.

It also introduced, for the first time in a significant way, artists embedded with U.S. troops, commissioned to capture truthful experiences of war in real time. This is the subject of the second half of the Smithsonian’s exhibit, which displays artwork from the eight artist soldiers who served with the American Expeditionary Forces.

The eight artists created more than 700 pieces of artwork in 1918, which are stored at the Smithsonian National American History Museum, according to Peter Jakab, chief curator of the Air and Space Museum. They changed the way war was portrayed in artwork, he said.

“Typically, a lot of art before this was done long after the battle, far from the battlefield, depicting very heroic impressions of the battle,” Jakab said. “The idea here was to create a sort of immediate, in-the-moment depiction of what was happening.”

Only a handful of the AEF artwork, which captures the cost of war, the technology, the battles and more, has ever been seen on display. Originally, the exhibit was just going to feature the commissioned pieces, until Jakab learned of Gusky’s work.

“It struck me that both of the collections would have greater power if they were integrated into a single exhibition,” said Jakab. “We have artists who became soldiers and soldiers who became artists, and they bring forth this individual experience and individual self-expression.”

Both collections reveal that timeless individuality, which, according to Jakab and Gusky, is relatable to how history and the civilian population view the military even today.

“When we think of great historical events, we always tend to forget that they are made up of experiences of individuals,” said Jakab. “Even something as profound as the First World War, it’s a collection of individual experiences, and the artwork really enforces that idea.”

The carvings are beautiful, sad, touching, religious, romantic and often funny. The most common carving, according to Gusky, was a simple heart.

“When someone is on their deathbed what matters is the people who love them and who they love,” he said. What’s more, the drawings overwhelmingly revealed “very clear love for this country … They put their lives on the line for it.”

The exhibit runs through Veteran’s Day, Nov. 11.