Image 0 of 8

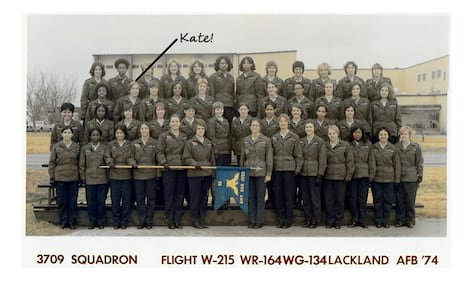

The first time Kate Kelly heard the warnings about George Air Force Base, she was a 19-year-old airman just getting settled into the barracks. It was 1975.

Another female airman sat on a bed opposite. She gave Kelly the rundown of the base. At the time, George was a hub of F-4 Phantom fighter jets and OV-10 Bronco reconnaissance planes.

Kelly mentioned she’d been thinking about getting married. Her roommate’s response was quick: “Just don’t get pregnant,” the airman warned. “Don’t get pregnant at George Air Force Base.”

Kelly didn’t think too much about the warning and went to work, to offload boxes from arriving aircraft.

“I started feeling the effects when I was on the flight line immediately,” Kelly said. She had urinary tract infections, bleeding and pain. The base clinic would analyze the infection, provide antibiotics.

Kelly learned by talking to other women in her unit that the infections were common, and among the female airmen on base, so was her roommate’s warning: Don’t get pregnant at George.

RELATED

She didn’t dig further as to why.

“You don’t ask questions like that. It doesn’t cross your mind,” she said. “You rely on the service to keep you safe. And although there’s no guarantee of safety, when you’re stateside you certainly don’t expect toxic exposure.”

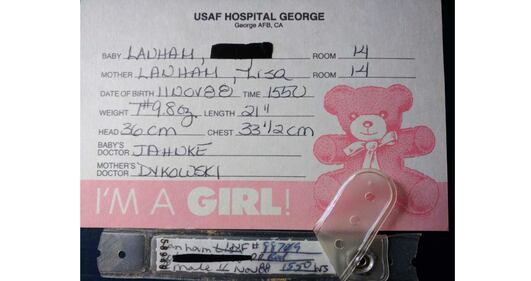

Lisa McCrea lived at George from 1987 to 1991, right before it was closed. The 19-year-year old military wife was in her second trimester when she began to bleed. She’d miscarried. By the time her husband got her to the base emergency room, he had to carry her in, she’d lost so much blood. A terrible operation followed.

The next day, a base doctor said her uterus “had more tumors than he’d ever seen,” said McCrea, now 50.

In multiple interviews with women who served at George or lived there, they recounted similar stories. Sometimes the base clinic doctors privately warned them. More often it was passed word-of-mouth. Some remember getting a briefing as they in-processed.

Kelly did get married at George, moved into family housing and got pregnant. She miscarried.

RELATED

Kelly was never able to have children and miscarried at least twice more, before she had to have a hysterectomy in 2012. In 2008 her then-former husband died as a result of a rare plasma-based cancer. In 2012, Kelly had a full hysterectomy to protect against dangerous tumors in her uterus. It wasn’t until then she decided to look into her military health past.

“I thought it was me,” she said of the failed pregnancies. “‘What am I doing? What is going on?’” Kelly said. “I learned this year that the base was a toxic base. I started putting two-and-two together. That’s when my symptoms started. When I was at George Air Force Base.”

Kelly isn’t alone. Nearly 300 women who lived at or served at George have connected over Facebook with similar health issues. Ovarian cycts. Uterine tumors. Birth defects in their kids. Hysterectomies. Based on an informal poll, 94 women reported miscarriages among just the 300 who responded. The stories span three decades, from women who were there in the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s until the base closed.

Now some of the women are questioning: Was it the water?

“The water supply ran right underneath the base,” McCrea said. “I was drinking the water out of the taps. And all of this was in our drinking water.”

George Air Force Base

George Air Force Base was selected for base closure in 1988 and shuttered in 1992, although the base was used as recently as 2002 for military exercises and a portion remains in use as the Southern California Logistics Airport Authority.

It was designated a Superfund site by the Environmental Protection Agency in 1990; George is still in a long-term program to clean up 33 separate hazardous wastes left there. Underground plumes of old jet fuel are in the water supply. Industrial solvents used to de-grease and clean jets left trichloroethylen, a chemical that attacks the nervous system, blood, kidneys, immune system and heart, remain in the water and soil.

Those are just some of the workplace hazards airmen there faced. In interviews, they described exposure to pesticides in the barracks and potential radiation exposure from working on the F-4’s nose cone.

McCrea thinks it was a combination of the contaminants that caused her miscarriage and subsequent other health issues.

In March, another known contaminant was added: the Pentagon reported to Congress that George Air Force Base one was of hundreds of military locations that had water sources testing higher than the Environmental Protection Agency’s recommended 70 parts per trillion maximum levels of perfluorooctane sulfonate or perfluorooctanoic acid, also known as PFOS and PFOAs.

At George, among the 22 monitoring wells DoD sunk to test water sources, 14 came back with PFOA or PFOA readings that ranged between 87 and 5,396 parts per trillion above the 70 ppt limit.

The man-made chemicals are found in everyday household items, but they are concentrated in the foam the military uses to put out aircraft fires. They have been linked to cancers, infertility and birth defects.

George is one of several Air Force bases with concerned current and former communities now coming forward about base contaminants. Last week, the Florida Department of Health said it is collecting cancer reports from current and former residents who lived on or near Patrick Air Force Base. The Michigan Department of Health is holding regular meetings with residents who lived around the former Wurtsmith Air Force Base to address contaminated private water sources. DoD tested 67 wells there, one came back reading almost 3000 ppt over the recommended exposure.

In early June the city of Dayton, Ohio, notified residents that it was installing 150 monitoring wells around its public water sources after water testing in February showed that “certain chemical contaminants are migrating from Wright-Patterson Air Force Base toward Dayton’s Huffman Dam wells into the ‘raw’ or untreated water we use as a source for some of our drinking water.”

“The sampling data strongly indicates that the contamination is the direct result of activities occurring on the Air Force base,” the city told residents in a February notice.

Officials with DoD’s Health Affairs Office stressed that until EPA showed interest in PFOS and PFOA around 2012, it had not had any indication of risk to forces or the bases.

“We don’t do the primary research in this area,” said Army Col. Andrew Wiesen, director of Preventive Medicine for the office of Health Affairs. The EPA is responsible for that, he said. DoD has not independently looked at the compounds and does not have “additional research into this, about the health effects of PFOS/PFOA, at least as far as I know.”

RELATED

Sen. Jeanne Shaheen, D-N.H., who represents another impacted base, Pease Air Force Base, got $10 million approved for nationwide study on health issues caused by exposure to the compounds in the 2018 defense bill. Another $10 million is included in the 2019 defense bill, which just passed the Senate. The full bill still needs to be reconciled with the House version then signed into law by President Trump.

If signed into law, the bill would also establish a national registry for families to report exposure to the compounds, much like former Iraq and Afghanistan veterans now register to report burn pit exposure to the VA.

Connecting the dots

None of the women at George Air Force Base suspected their illnesses might be tied to their military service until they connected online. The websites that tied them together are run by Frank Vera, a former weapons systems specialist at the base. He started a Facebook page and a separate website on the contaminants to “try to unravel what I was exposed to at George.”

That’s what Denise Torri unexpectedly found when she began a web search about three years ago. It was near Veterans Day, and she was nostalgic. She wanted a picture of her OV-10 Bronco to post.

Torri and her husband served at George together from 1986 to 1989, she was an aircraft maintenance scheduler for the OV-10s, he was a weapons armament specialist. They got married in 1987 and got pregnant soon after. She miscarried.

When she went back to the base doctor, she heard the warning, too. “Don’t get pregnant.”

“Wouldn’t you just assume it was to get you to relax [in order to have a successful pregnancy]” Torri said. “You don’t think they are really telling you, ’Don’t get pregnant.’”

A while after Torri’s miscarriage, her supervisor, a staff sergeant, asked her for a personal favor. Could she please go to his home and clear out the nursery?

The staff sergeant’s wife had just miscarried their late-term child.

“It was just a weird feeling, taking the crib down,” Torri said.

Torri’s next pregnancy was successful, but was followed by another miscarriage.

Where are the records?

Lorie Clark and her husband served at George from 1981 to 1983; both were aviation repair technicians who’d met in tech school. It was a base doctor who warned her about pregnancy and the high rate of miscarriages at George, “but he didn’t give me any indication on why,” she said.

Clark initially had infertility issues, but birthed two daughters while stationed at George. Both daughters have had miscarriages of their own and all three women have a variety of chronic illnesses.

So Clark went looking for her medical past.

“I keep getting the run around,” Clark said. “It’s like they aren’t able to provide anything at this time.”

Now Torri is angry at the idea that the base knew for decades that there was danger but did nothing. In the last few years she’s sought her medical records from George to file VA claims.

“They had purged everything,” she said.

McCrea can’t get her records either.

“I have requested them but, they are withholding most people’s records.,” McCrea said. “Especially if they were sick while they lived there like I was.”

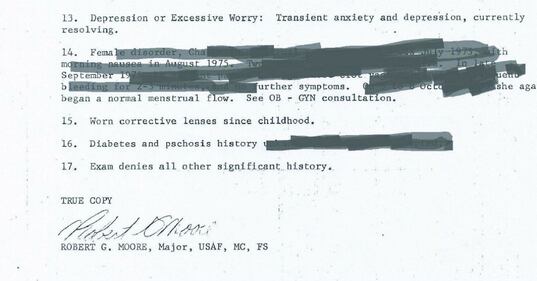

Kelly has a file with about 300 pages. But the medical records from George carry no record of the pregnancy. Some pages are redacted with marker lines of blackened sentences.

Wiesen said it would be unusual for a service member to get redacted records of their own files.

“The official policy for medical records is the records themselves are the property of the U.S. government,” Wiesen said. “But the individual has the right to review them. and request that any corrections to the records be made.”

On the redactions, Wiesen said, “I can’t comment on any specifics, but it would not be general policy to redact any part of your medical records, because there’s no reason to do that.”

Moving forward, the department is ready to assist in any future studies, said Steve Jones, a director in the health affairs office.

“What we would do at the department is make our resources available to the agencies that would have an interest in studying the effects in contamination, not only at George Air Force Base but any base,” Jones said.

As more information on what was in the water becomes public, McCrea thinks the number of military communities who will start to question what they were exposed to will continue to grow.

“I am in contact with several people from different bases,” she said.

This story has been updated to reflect that McCrea’s miscarriage occurred in the second trimester, not third.

Tara Copp is a Pentagon correspondent for the Associated Press. She was previously Pentagon bureau chief for Sightline Media Group.