WASHINGTON — The blast of specially designed bombs used to kill or maim more than 1,000 U.S. troops during the war in Iraq can seem to the victims to come from nowhere.

In a flash, liquefying metal shredded even armored vehicles and bulletproof glass. The aftermath of those bombings can seem a chaotic scene.

But to the trained eye, small details left at what becomes, essentially, a crime scene, reveal telltale patterns and physical evidence. That evidence marks a trail not only to the local attack but the source of the training and devices.

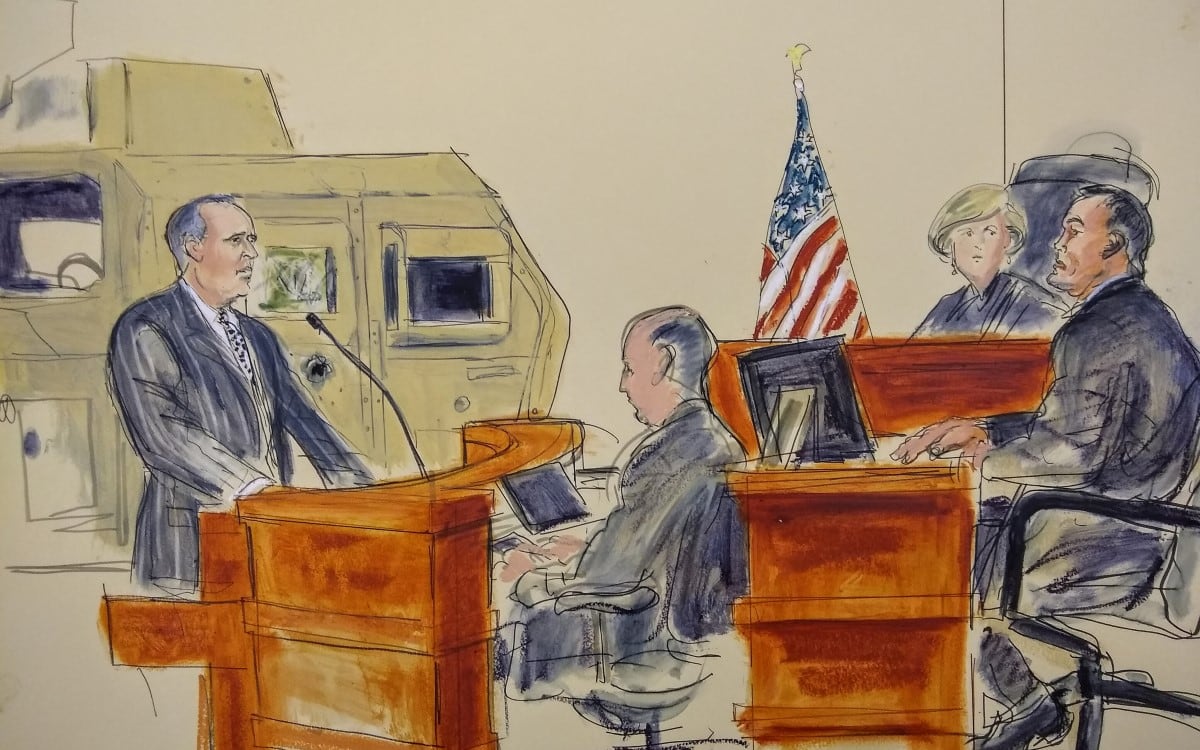

During the second day of a federal trial in which civilian law firms and hundreds of victims of terrorist bombings and attacks during the Iraq War are taking on the Islamic Republic of Iran, experts on explosives, trauma and brain injuries connected dots between the origin of attacks and the lingering pain and suffering that resulted.

The improvised explosive devices used against U.S. and coalition forces in the early days of the war were often exactly that — improvised.

Often, insurgents and terrorists would simply grab from the stockpiles of old munitions, of which plenty dotted the landscape, and apply simple triggering devices. A common device was an artillery shell wired to explode after a vehicle ran over a homemade pressure plate.

Those devices did kill and maim. But fairly quickly, coalition forces found ways to counter them.

RELATED

Army Capt. Wade Barker, who served multiple tours in Iraq and Afghanistan both as a soldier and later as a civilian contractor focusing on countering explosive devices, testified on Tuesday that soon after the invasion of Iraq, more sophisticated bombs and methods of deploying them took shape.

The ongoing trial is an effort by attorneys with the Osen law firm out of New Jersey and Tab Turner, an Arkansas-based attorney, to connect to Iran weapons, training and tactics used by terrorist groups in Iraq against coalition forces. If successful, the $10 billion lawsuit could mean the plaintiffs in the case would become eligible for financial compensation from a specially designated fund for victims of state-sponsored terrorism.

And its not a practice in legal theory. More than $1 billion has already been paid out to victims from fines and seized or forfeited funds, mostly through cases against banks that laundered money for Iran, which prosecutors allege was then used to fund these terrorist attacks. There are multiple other cases, including one by MM-Law out of Chicago, that are attempting to make similar connections involving Iran and al-Qaida.

The key type of weapon used was the “explosively formed penetrator.” The EFP was used in most, but not all, of the 90 attacks being submitted in this current court case to help establish links between Iran and the attacks.

Barker explained in great detail the methods by which IEDs and then EFPs were deployed. Most IEDs, even those that used artillery shells as opposed to homemade explosives, could be defeated by armor plating applied to Humvees.

Such attacks typically had little effect on more heavily armored Bradley Fighting Vehicles or tanks.

The EFPs were a much different story.

Machined from steel casings that hold the explosive and the 140-degree copper discs that formed into perfect penetrators, capable of punching 4-inch holes through multiple layers of armor and pulverizing ceramic plating into dust, the EFPs revealed engineering and designs that far exceeded what a typical insurgent could build.

The EFP device allows for the blast to push the copper plate out, reforming into a “tear drop” shape under the extreme heat and traveling at 26,000 feet per second.

Not much can stop it.

Earlier in the trial, attorneys laid out the trail of support from Iran to attack through testimony from civilian experts on terrorist groups backed by Iran, such as Hezbollah, and military leaders who commanded vast swaths of Iraq that saw major attacks by Iranian-trained militants.

Barker walked the attorneys and judge through a scene-by-scene playing of video that captured such blasts in controlled Army laboratories.

The projectile’s speed helps it defeat armor, and the armor doesn’t have a chance to absorb the focused impact, as it might with more conventional projectiles.

It is those characteristics — how the EFP punches through armor, the traces of copper and different explosives and the shape of the hole — that tell experts such as Barker what kind of bomb wreaked havoc in a particular attack.

Charred auto parts, copper tailings, explosive traces and measured holes build hard physical evidence that point to the guilty party, much like in a murder case.

And in this case, attorneys say, the evidence points to Iran.

Barker served as an expert witness, analyzing a handful of the 90 attacks listed in the lawsuit. Not only did the attacks he analyzed include the physical traces, they also included more sophisticated techniques that militants employed likely taught to them by Iranian or Hezbollah trainers.

For example, nearly all of the EFP devices used a method that included a cell phone call and a PIN to turn on the device. Within seconds, the motion sensor, common to civilian home alarms, would come on.

The sensor detects both heat and motion through a Passive Infrared device, or PIR. The combination of the EFP and the PIR system made for a very deadly and also very accurate weapon that could be put in place and used at will, from a distance.

But, an enterprising soldier figured out a way to minimize the effect, first by strapping an ammo can with warm liquid to a pole that was fitted to the front of the Humvee. That way, the can would trigger the blast.

The method was later adopted and called a RHINO anti-PIR device. While the bomb would still explode and take out the front of the vehicle, it often avoided injuring those inside.

Then, bomb planters evolved.

They shifted the aim of the EFP while leaving the triggering mechanism in place, effectively defeating the RHINO.

The ignition systems and machined parts, together with the methods used, point to “hallmark” signs of attacks then used by Hezbollah, an Iranian backed terrorist group based out of Lebanon but with global reach.

The items used and their configuration required a “classically trained engineer,” Barker testified.

Beyond the blasts remain wounds that troops suffered, both mental and physical, for which the more than 200 plaintiffs in this case, both victims, their families and survivors of those killed, are seeking.

For hours on Tuesday, both Charles Marmar, a high-level expert on post traumatic stress disorder, and Dr. Russell Gore, a former Air Force flight surgeon and brain injury specialist, detailed the effects that not only combat but bomb attacks and EFPs can create.

More than simply the standard, life-altering trauma of combat, bomb attacks can combine to create a combination of both physical and emotional wounds that a survivor can find impossible to shake.

For example, if the face and hands are burned or disfigured, Marmar said, “the trauma is imprinted on the body.”

“They literally can’t escape the trigger,” he said.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.