Last spring Military Times reported that the Navy, Marine Corps, Army and Air Force’s aircraft were in deep trouble. Manned aviation accidents had spiked almost 40 percent over the past five years, killing 133 service members since 2013.

More catastrophic crashes followed and Congress got laser-focused on the problem. After multiple hearings, lawmakers injected $39.4 billion into this year’s budget “to begin to overcome the crisis in military aviation by getting more aircraft in the air.” Capitol Hill also passed legislation creating a National Commission on Military Aviation Safety.

No one expected a quick fix. The 2013 budget cuts — known as “sequestration” — had contributed to a hollowing of the maintainer force, an exodus of skilled pilots and had left aircraft without spare parts, rendering them unable to fly. At the same time, intensified air operations against the Islamic State and back-to-back years when Congress was unable to pass a budget on time compounded the problem. The accidents climbed.

So now, a year later, and again through multiple Freedom of Information requests, Military Times has obtained updated data to report on every major aviation accident that has occurred during the past year to answer the question: Are things getting better?

For too many military families, the answer was no. Military aviation accident deaths hit a six-year high in fiscal year 2018, killing another 38 pilots or crew.

Of those most recent deaths, 24 were killed on training flights. Two were crew killed by rotor blades; another died when an HH-60H Navy Pave Hawk fuel tank dropped and struck him. Eleven died in non-hostile aviation accidents that occurred while they were deployed.

For comparison, in that same time frame, 25 service members died in attacks in Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan.

Those 38 aviation fatalities in 2018 brought the total number of service members killed since 2013 in aviation accidents to 171.

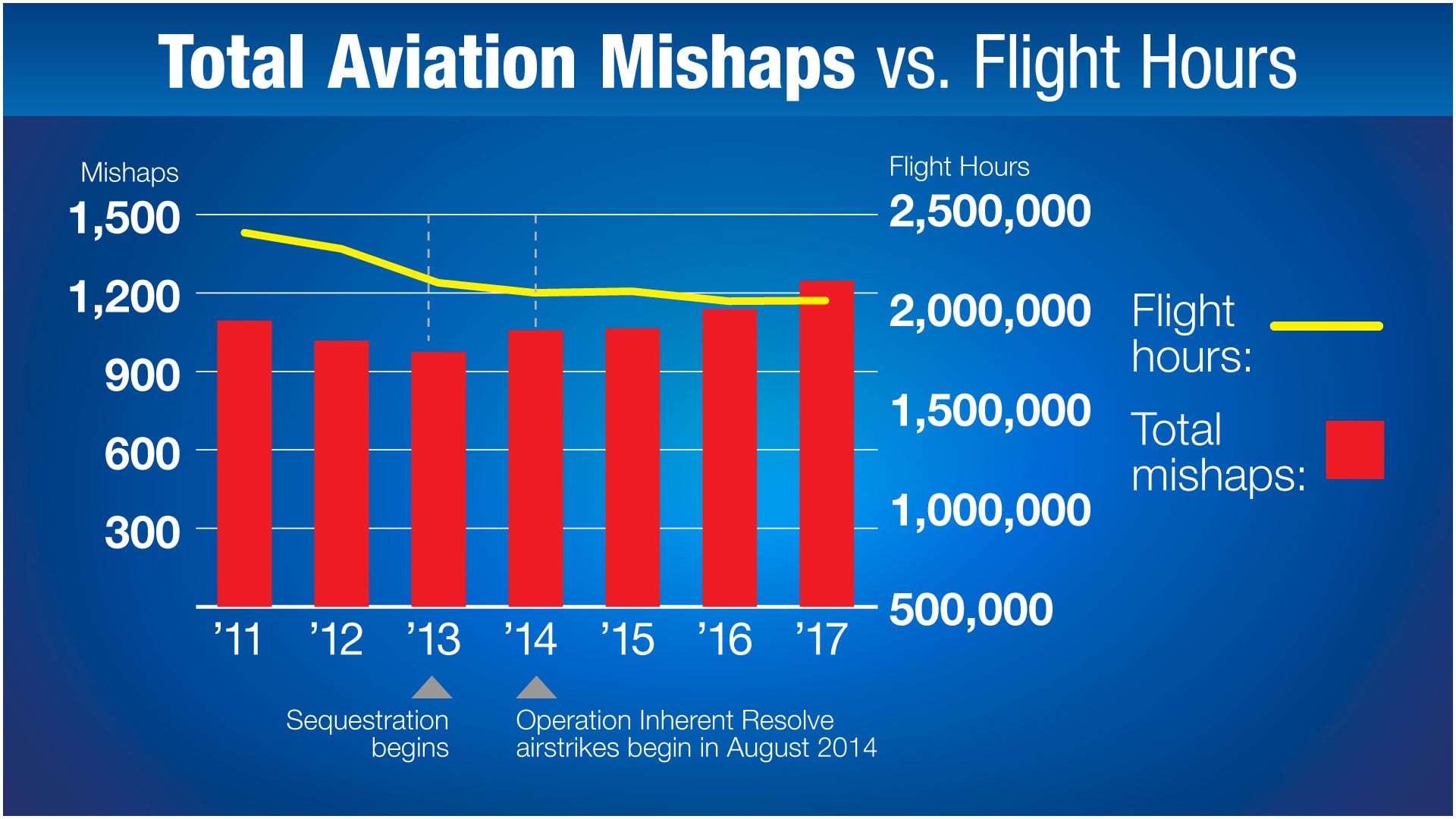

But there was good news, too. The total number of military aviation accidents fell last year for the first time since the 2013 budget cuts.

Total accidents involving the nation’s manned warplanes — fighters, tankers, helicopters and bombers — decreased 12 percent last year, dropping from 903 mishaps in fiscal year 2017 to 794 in fiscal year 2018, according to data updated through fiscal year 2018 and obtained by Freedom of Information Act requests to the Army Combat Readiness Center, the Air Force Safety Center and the Naval Safety Center.

Across all platforms, manned and unmanned, the number of accidents fell 10 percent, from 1,239 in fiscal year 2017 to 1,125 in fiscal year 2018.

Military Times has re-published that data in a searchable database which now contains the almost 8,700 manned and unmanned mishaps from fiscal year 2011 through fiscal year 2018. The database can be searched by year, type of aircraft, service and location.

RELATED

The drop in the number of accidents was welcomed, with caution.

“It seems to me we have turned the corner,” said House Armed Services Committee ranking member Rep. Mac Thornberry, R-Texas.

But Thornberry worried that the improved mishap rates would convince lawmakers that military aviation has fully recovered and no longer needs the increased spending and attention.

“All the service chiefs said ‘it takes time to recover from a readiness hole like this,'” Thornberry said in an interview with Military Times. “It’s just that we in Congress seem to be impatient, and think ‘OK, I’ll fix that, I’ll put some money on it and move on to another problem.' We cannot afford to do that. If we move to another problem, we’ll make a 180 [degree turn] and go back downhill, fast.”

But others questioned whether accident rates, which will never be perfect, should justify another large increase in defense spending. In light of a $164 billion overseas contingency operations budget request that has little transparency and the administration’s decision to tap into billions of dollars in military construction funds to build a border wall, priorities may be shifting. Many are asking: is there really a crisis?

“We got a $750 billion budget request from the president,” House Armed Services Committee chairman Rep. Adam Smith, D-Wash., said at a budget hearing last week. “We could throw money at [DoD] all day long and you’re going to come back at us and say there’s still an unacceptable level of risk."

That message comes as House Democrats prepare a key vote this week on lifting spending caps for both defense and non-defense programs in next year’s budget.

The idea that the services are no longer in an aviation crisis is dangerous, one current Air Force pilot told Military Times on the condition he not be named.

The pilot said he has seen Air Force leadership spend a lot of time with aviation units during this last year addressing safety issues. He’s seen specific improvement, but “unfortunately senior leadership across many commands have stopped talking about the crisis or have told us there isn’t a crisis,” he said.

But there’s still a lot of vulnerability. New pilots are too inexperienced and are getting qualified without the same level of skills or requirements in order to build up the ranks. That fuels skepticism that things will continue to improve.

“The Air Force is happy to attempt to grow themselves out of the situation, which will only further exacerbate our situation by flooding squadrons with young pilots,” the pilot said.

Here’s an update by service:

Marine Corps

This year the Marines registered their first annual decrease in aviation accidents since 2013. The Marines reported 101 total accidents in 2017, this year they’ve got the numbers down, reporting 85.

They aren’t out of trouble yet though. Total accidents are still up 50 percent from 2013, a number they hope to bring down through continued attention to ground operations and maintainer retention.

RELATED

The Marines are also targeting their Class C mishaps for improvement. They realized a lot of those were occurring due to flight line sloppiness. In response the Marines had every wing implement stricter towing policies. They also looked at flight operations, particularly for the V-22 Osprey, and “totally revamped the way we do reduced visibility landings and shipboard landings,” said Col. Byron Sullivan, director of the Marine Corps’ safety division.

To begin to heal from the 2013 cuts to high-skilled personnel, the Marine Corps also began investing heavily in their maintainers with new personal protective equipment, new workstations and a $20,000 bonus for qualified maintainers who signed up for another four years of service.

They’ve also learned that in any future budget cuts, they won’t target operations and maintenance to cut spending.

These days, “we are fully funding our maintenance and readiness efforts before we do anything else,” Sullivan said.

Navy

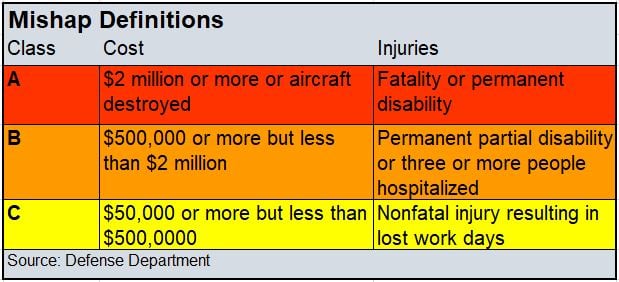

The Navy was the only service to get worse, not better, over last year. Total accidents climbed from 226 in 2017 to 232 this year, and the Navy’s accident rates are still 83 percent higher than they were in 2013. The Navy’s F/A-18E Super Hornet was again a primary contributor to the increase. Class B mishaps involving the Super Hornet jumped from 4 to 10 from 2017 to 2018, and Class C incidents for the Super Hornets similarly spiked, from 36 in 2017 to 45 in 2018.

RELATED

When the Navy first saw its end of fiscal year totals last October, they were blunt.

"The hole’s a little deeper than we thought,” Vice Adm. DeWolfe “Bullet” Miller III, the commander of Naval Air Forces, said at a Washington think tank event shortly after the final numbers were out. "We didn’t get here overnight and we’re not going to get out of it overnight.”

In response to the spiked accident rates, the Navy undertook multiple reviews. Based on that feedback, the Navy revised flight regulations to better protect against aircrew fatigue. It began deep dives with the Center for Naval Analyses on identifying the impact of decreased maintainer experience. Going forward, all Naval aviation will conduct safety stand-downs once a quarter, said Naval Air Forces spokesman Cmdr. Ron Flanders.

What the Navy needs is time for the many safety initiatives it has undertaken to take effect, and its already seeing some improvement in its fiscal year 2019 rates to date, Flanders said.

Air Force

While Air Force numbers overall improved, the number of Class A mishaps — the highest level, meaning destruction of the aircraft, death of a crew member or damage totaling more than $2 million — jumped. There were 17 Class A mishaps in 2017; 27 Class As in 2018.

For many of those cases, the incident rose to the level of a Class A because of the cost of the aircraft. For example, when the landing gear on an F-35 collapsed at Eglin Air Force Base last August, it caused $2.3 million in damage. There were nine such Class A mishaps involving either their advanced F-22 or F-35A fighter aircraft, none of which were fatal. But they still meant a downed warplane as it went through repairs, which means fewer aircraft available to fly and train on.

RELATED

“That was one of the things that got our attention,” Maj. Gen. John Rauch, chief of safety for the Air Force, said in an interview.

But there was a high-profile increase in fatal accidents, too. In May a string of Air Force crashes killed Air Force Thunderbirds pilot Maj. Stephen Del Bagno during a training flight. Seven airmen were killed during a transit flight on an HH-60 Pave Hawk in Iraq. Then, in an accident caught on camera, a Puerto Rico Air National Guard WC-130 crashed violently in Georgia, killing all nine crew aboard.

The Air Force ordered a service-wide operational safety review.

A series of blunt but private conversations among units about individual safety cultures followed, Rauch said.

“They were discussing mishaps at kind of the safety-privileged level,” Rauch said. The Air Force took the notes and findings from each unit-level discussion and looked for trends. What they heard: high operations tempo had taken a toll. Pilots did not have enough time to focus on flying basics. There was pressure to always execute the mission, despite risk. There weren’t enough available aircraft, and crews had become complacent during routine tasks.

RELATED

The Air Force took some initial actions, such as cutting the amount of non-flying tasks assigned to air crews. It’s also working with the other services and the Defense Department on potentially adjusting the cost criteria for what counts as a Class A, to better reflect the number of advanced aircraft they now operate.

“Not that we discount those mishaps, at all,” Rauch said. “But they end up in a different category than they would be otherwise.”

Army

Compared to the other services, the Army’s mishap rates have held relatively steady since 2013, where draw downs in Iraq in 2011 and the phased reduction in forces in Afghanistan provided the Army some relief from operational strain. For 2018, the Army was the only service to bring its total number of mishaps — including all manned and unmanned platforms — below its 2013 rates.

However, if the Army data is filtered to only look at manned aviation mishap rates, the numbers do not look as good. Manned aviation accidents jumped from 71 incidents in 2017 to 85 in 2018, largely because of an increase in Class C mishaps involving UH-60 Black Hawks.

The Army has already targeted those Black Hawk incidents through additional training and animated vignettes that recreated to teach lessons learned from each one. The incidents are called “near misses, because they could have been much worse,” said Army Col. Chris Waters, deputy commander of the Army Combat Readiness Center.

As a whole though, the Army’s improvement was primarily driven by a sharp drop in accidents with the RQ-7 Shadow UAV. Over the last several years, Shadow mishaps have steadily contributed to a rise of dozens of lower-level accidents for the Army.

“RQ-7s, because of their dollar value, don’t ever reach the Class A threshold,” Waters said. “But they were registering plenty of Class Cs.”

The Army looked for trends in the Shadow mishaps and saw that propulsion system errors were a frequent contributor to the mishaps. That system is now getting a block upgrade. They also decided that UAV operators would now be trained specifically to one platform, instead of generalized training that had allowed them to operate multiple platforms.

Military Times Deputy Editor Leo Shane and Air Force Times reporter Steve Losey contributed to this report.

Tara Copp is a Pentagon correspondent for the Associated Press. She was previously Pentagon bureau chief for Sightline Media Group.