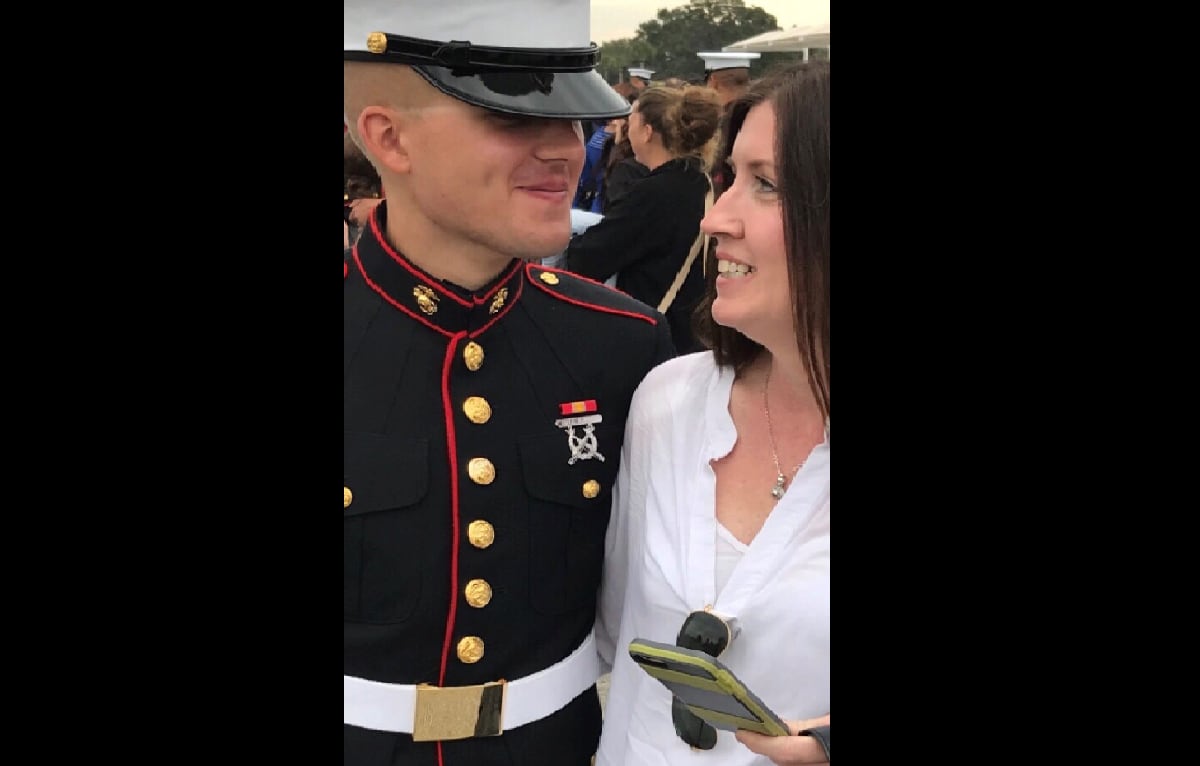

After her son died of a flesh-eating bacterial infection in early 2018, while stationed at Twentynine Palms, California, Lynda Kiernan filed inquiries with her congressional representatives ― and learned that because Pfc. William Becket Kiernan was a Marine, the Navy doctors who failed to diagnose his condition would face no repercussions.

Now, she is waiting to see whether Congress passes the Richard Stayskal Military Medical Accountability Act, which would overturn part of the Feres Doctrine, a 1954 Supreme Court decision that prevents service members or their families from filing suit for negligence against troops, including medical malpractice. The bill is being held up in a dispute over border wall funding.

“For me, the way we have to go about it is a monetary suit,” Kiernan told Military Times on Tuesday. “But that is not my goal, at all. I don’t care about monetary compensation.”

Kiernan’s son, who went by Becket, was 18 when he arrived at Twentynine Palms after boot camp, to get trained up as a field radio operator. Less than two months later, he was dead.

A spokesman for Marine Corps Combat Development Command did comment by deadline.

“Something happened,” Kiernan said. “He became very sick.”

In pain and experiencing flu-like symptoms, she said, Becket went to medical some time in January, at her urging. Everything was fine, he told her, as he spent his free time laid up in the barracks, with friends bringing him food and Gatorade.

“I found out later he was turned away,” Kiernan said, adding that members of her son’s chain of command surmised that, because there was no record of him going to medical, “he was probably told he was being a malingerer and sent away.”

But then he was pulled out of training, she said, with severe leg and hip pain, shaking uncontrollably, his skin turning blue.

“Even though his flu test came back negative, they told him he had the flu,” she said, sending him back to the barracks for two days of “sick in quarters” leave.

They also told him to give money to his roommates to bring him supplies, including medicine for his symptoms. That was Friday, Feb. 2, she said, and before dawn on Sunday, he called to tell her the pain had kept him awake the entire weekend.

“Becket spent the last two days of his life alone in his barracks, not checked on,” she said.

He made his way to the on-base hospital again, she said, where he was still not diagnosed.

Later that day Kiernan got a call from a civilian regional medical center, telling her that they were trying to figure out whether it was a blood clot or an infection causing Becket’s illness.

She caught the first flight out of Boston in the morning, calling for an update during a layover in Chicago. The doctor on the other line was evasive, she said, but eventually told her it was flesh-eating bacteria, and “anyone who loves this boy needs to be here right now.”

A few Marines in civilian clothes met her when she deplaned in Palm Springs, missing her son’s death by a couple of hours.

The aftermath

When medical staff at Twentynine Palms got in touch, she said, she was horrified by their nonchalance.

“Well, it was the weekend,” she recalled one responding, when she asked why they didn’t tell anyone in his command how sick he was, to the point of needing transfer to another hospital.

No one in his chain of command had checked in on him that weekend, either, she said.

“From the doctors right on down through his chain of command, he was abandoned and alone,” she said. “He got himself back and forth to the hospital alone. Every step of the way, he suffered alone. He died alone.”

She opened both a congressional and a Senate inquiry into his death, but both were rejected because of Feres. So she wrote letters to top military officials, including the Navy surgeon general, Navy secretary and then-Defense Secretary James Mattis.

Mattis’ office got back to her, letting her know her son’s case had been referred to the Marine Corps inspector general and she could expect a response in August.

“But when the date came, I got another letter saying, ‘Well, we conducted an investigation, and it was thorough,’" she said. " ‘It was a good investigation, but because of [federal law], you’re not allowed to know anything about it.’ ”

The law, section 1102 of U.S. Title 10, makes medical quality assurance records confidential.

The letter, signed by Maj. Gen. David Ottignon, described Becket’s death as “heart wrenching for me personally" and the investigation into his medical care “extensive,” including undisclosed improvements that the Bureau of Navy Medicine could make in its wake.

RELATED

A similar situation resulted in the partial leg amputation of a Fort Benning, Georgia, Army trainee earlier this year. As a strep throat outbreak plagued his unit, Pfc. Dez Del Barba’s excruciating leg pain went undiagnosed for weeks.

After he collapsed in the barracks, doctors finally diagnosed a flesh-eating bacterial infection and he was flown to Joint Base San Antonio, Texas, for extensive skin grafting to save his lower body.

An investigation at Fort Benning denied the accusation that drill sergeants had discouraged trainees from going to sick call, but did find that the protocols for treating trainees complaining of illness needed to be improved.

Fighting back

After Becket’s story appeared in Newsweek, Kiernan got in touch with Khawam. She filed a claim under the Federal Tort Claims Act, but it was blocked by Feres.

“This denial is another example of how unjust the Feres Doctrine is, and why we need to pass the SFC Richard Stayskal Military Medical Accountability Act,” she told Military Times.

Khawam also represents Stayskal, in addition to other service members and veterans seeking compensation from the Defense Department after alleged malpractice and other negligence.

RELATED

“Our service members are out there fighting for our country, but dying from medical malpractice at DoD hospitals,” she said.

Though Feres prevents claims on behalf of service members in all scenarios, the bill would remove medical malpractice from that list.

The bill, introduced as part of the proposed 2020 National Defense Authorization Act, is held up in the Senate Armed Services Committee, as arguments over border wall funding continue to hamstring defense spending.

“What I care about is that the Navy hold its medical staff accountable the same way that their medical staff would be accountable if it was a military spouse or a child,” Kiernan said. “For some reason, they treat active military members as a different class of patient, a different class of people.”

Without any fear of malpractice lawsuits, she said, it will continue.

“The only reason is because they can, with impunity,” she said. “And that, to me, is sickening.”

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.