Though the Pentagon has acknowledged the risks posed by breathing fumes from burn pits used to dispose of trash downrange, it can be difficult for service members and veterans to get care based on the time they spent around them. A pilot project from the Center for a New American Security and the Wounded Warrior Project aims to help troops connect those dots.

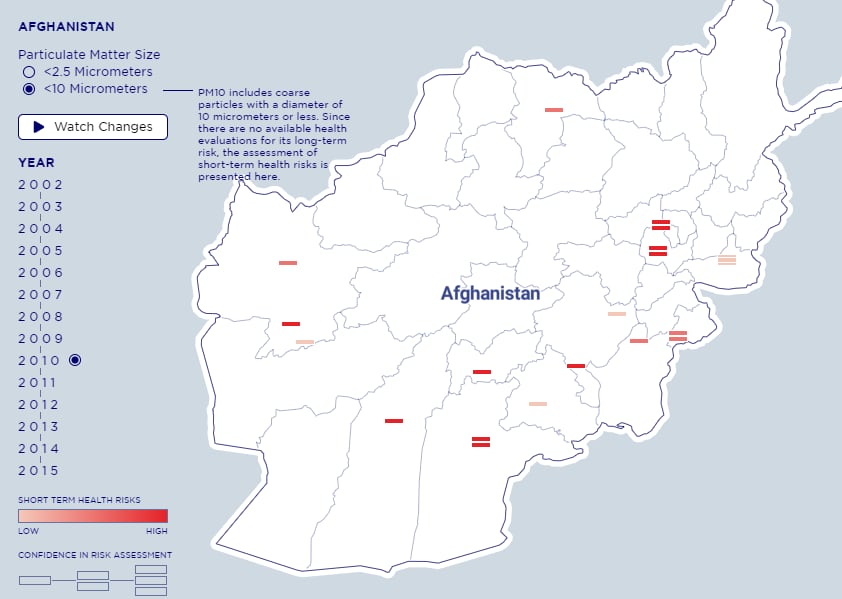

Using the Defense Department’s own records, a team put together two maps, broken down by location, time period and types of particulate matter recorded. Veterans can pinpoint their potential exposure based on their past deployments, look up those documents and share them with their medical providers.

“While these files do exist ― they are available and folks can go and download them and look ― for the layperson to be able to know that these files are there and know what to pore through would be difficult,” Kayla Williams, a former Army linguist and director of the Military, Veterans, and Society Program at the Center for a New American Security, told reporters Wednesday.

The maps show particulate tests of both less than 2.5 micrometers and between 10 and 2.5 micrometers, measured at different sites across the countries over a period of years. The shade of red at each site indicates the short-term health risks evaluated.

They shouldn’t be taken as gospel, Williams said, because DoD hasn’t done a thorough job documenting exposure to the tiny particles and vapor droplets launched into the air by burning food, equipment and other refuse in open pits. You can tell the Pentagon’s level of confidence in those calculations based on how many dashes are used to indicate each site.

“... we do caution that, again, the information as it’s currently available is simply inadequate for most locations,” Williams said.

The pilot ended up having two purposes, in effect: It sought to create a heat map of potential risks, but it also concluded that DoD did an insufficient job of cataloging those risks in the first place.

“So, somebody like me – I personally was in Iraq in 2003,” Williams said. “There’s some information here on the short-term health risks I may have been exposed to – much less on the potential long-term health risks. Virtually no information is here.”

According to the report, the Periodic Occupational and Environmental Monitoring Summary files are sketchy at best. Because over half of the summaries available didn’t have enough data in them to determine risks, either in the short or long term, Williams said, only a small sampling of burn pit sites in Iraq, Kuwait and Afghanistan could be included on the maps.

“Inconsistent collection, assessment, and presentation of available data seriously weakens the potential utility of the POEMS files as the primary source of information on toxic exposures,” according to the study’s executive summary.

RELATED

For example, the POEMS generally noted higher risks in locations where the most samples had been taken, begging the question: If more samples had been taken at other, “lower risk” sites, would their risk factors also shoot up?

So while veterans can use the heat maps to track down the specific risk assessments for their stints downrange and share those with a doctor, according to the study, the documents should not be cited as a source to deny anyone’s claim of toxic chemical exposure.

There are still nine burn pits officially in use, one in Afghanistan and seven in Syria, according to a July report from the Pentagon. And they will continue to be used in places that lack infrastructure for traditional trash disposal.

“Open burning remains a field expedient alternative to reduce waste volume and protect troops from disease,” the report said.

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.