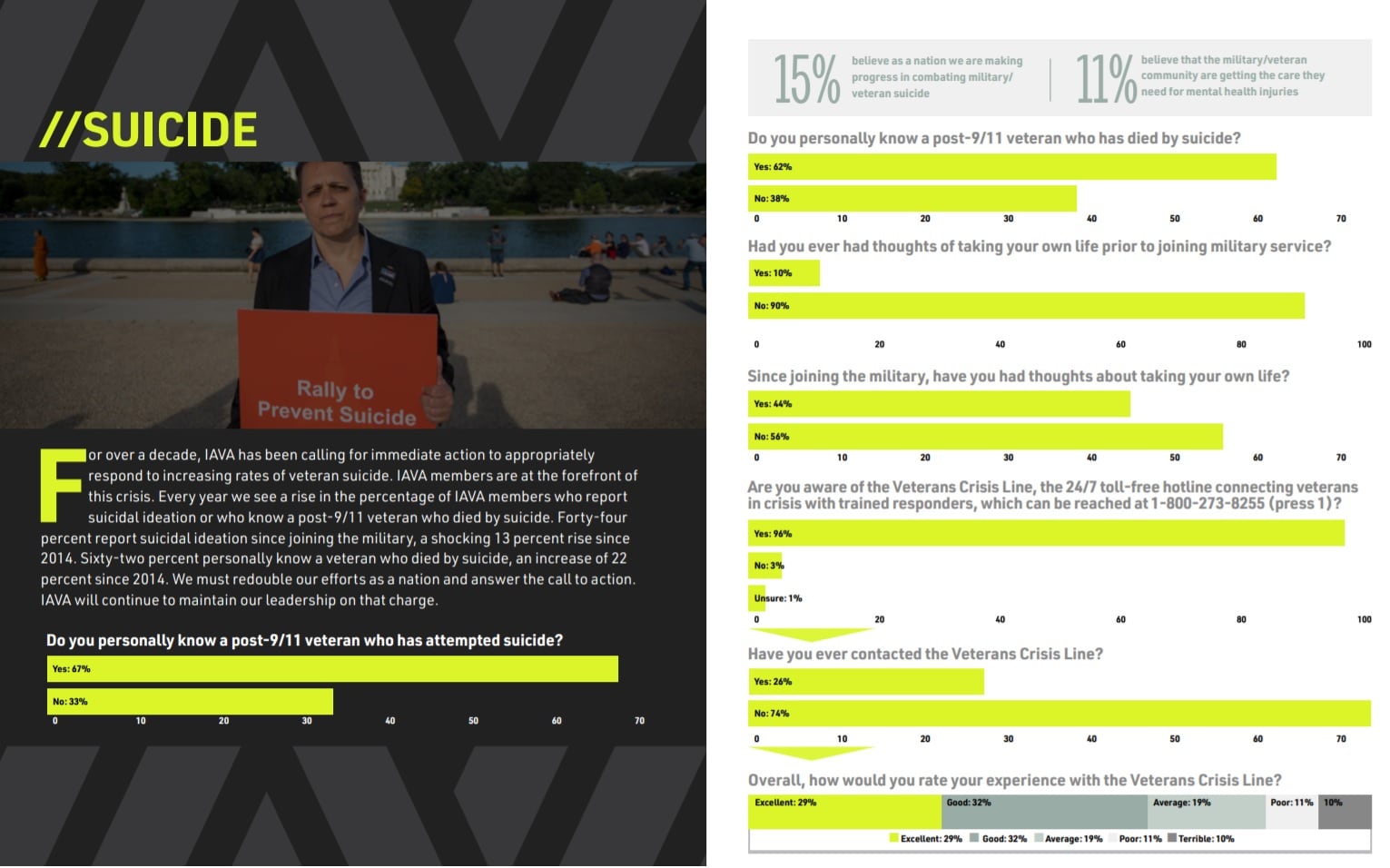

The National Guard’s suicide rate has surpassed their active-duty counterparts over the past three years, but there is confidence that things are turning around, a Guard senior health official told reporters Thursday.

Though they track each event internally throughout the year, the Guard’s director of psychological health told Military Times, the numbers have to be vetted by the Defense Department before they are officially released every fall, and so aren’t publicly available right now.

“We do anticipate that the numbers will be lower for 2019,” said Capt. Matthew Kleiman, a U.S. Public Health Service officer, after reaching a high of 135 in 2018.

With National Guardsmen dying by suicide at about a 5 percent higher rate than their active-duty counterparts, headquarters is looking at almost a dozen service member-generated initiatives to support the physical and mental health of its troops.

RELATED

At the same time, the organization is collecting data through its Suicide Prevention and Readiness Initiative for the National Guard program, using that to inform its strategy.

“Much of what’s done around suicide prevention is based on, you have people who are very passionate about the topic, who want to do something good to prevent death and to save lives, but without data, it’s hard to measure progress and it’s hard to continue to get resourced and funded for those things,” Kleiman said.

Data can identify gaps, he said, and then help prioritize where funding goes.

National Guard members, who spend one weekend a month with their units and another two weeks a year in training, can live and work hundreds of miles from other members of their units, making it harder to keep in touch and intervene when someone isn’t doing well.

“It’s hard on the unit, it’s hard on the people in the unit, who are very hard on themselves because they feel a responsibility for preventing those types of things,” said Maj. Gen. Dawne Deskins, the Guard’s director of manpower and personnel policy.

And further, unlike the active duty, when someone does reach out and pursue help, they aren’t able to walk over to on-base behavioral health providers.

“When you talk about getting someone help in the Guard, what you’re usually talking about is connecting that person within their community to a provider,” Kleiman said.

RELATED

The Warrior Resilience and Fitness Innovation Incubator is trying to bridge some of those gaps.

Currently, there are 11 pilots based in Massachusetts, Connecticut, Ohio, New Mexico, South Dakota, Montana, South Carolina, Georgia and California, selected about of 52 proposals submitted for 2019.

They include the Embedded Clinician Program, which makes behavioral health professionals available during every drill weekend in Connecticut; Work for Warriors, which helps Guardsmen with the civilian job hunt in Georgia; and the CAF Wellness Initiative, which has monthly social events in Montana.

Another, Primary Prevention & Retention based in New Mexico, screens new recruits.

“We want to know if someone’s coming into the National Guard with a history of problems that can impact their ability to be as resilient as they need to be to do the mission,” Kleiman said.

While recruiters and military processing staff ask very targeted questions about past suicidal thoughts or other self-harm, these guardsmen are looking for a more broad set of risks.

“They’ve developed a screening tool that focuses on early adverse childhood experiences, so it’s well beyond what the recruiters would ask,” he added.

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.