It takes tens of thousands of dollars to get a new service member through recruiting and initial training, and costs the services hundreds of millions a year when new troops are discharged from the military before the end of their first contracts.

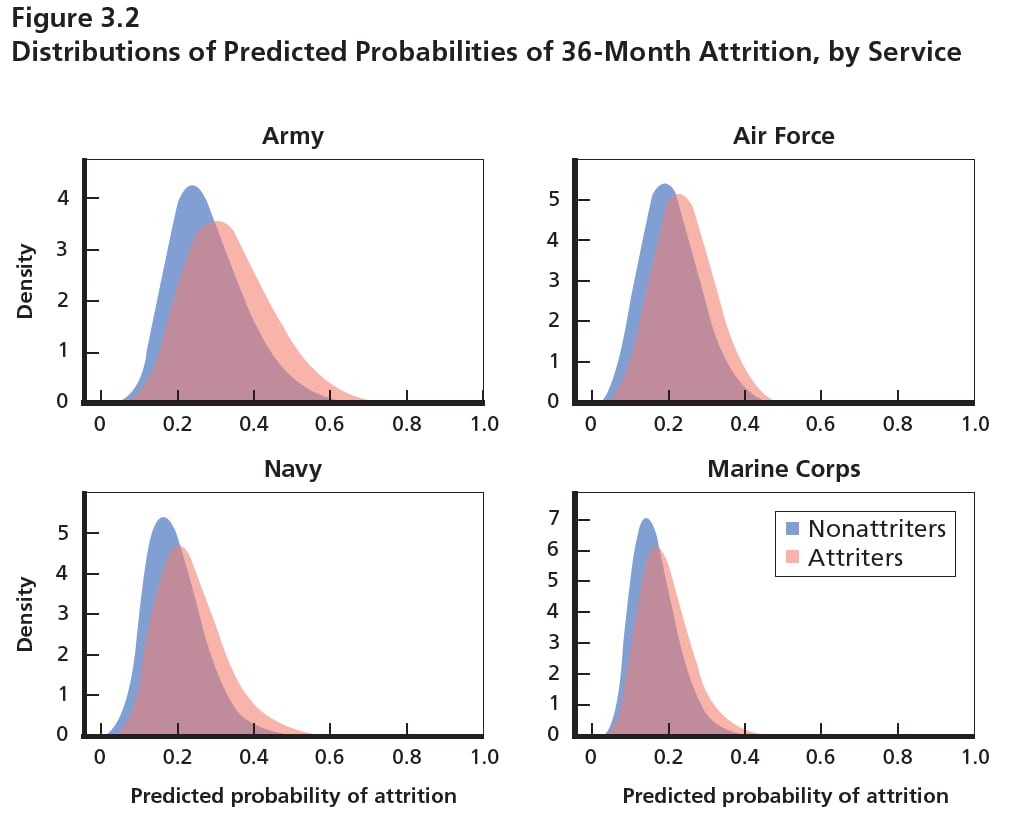

While there are some indicators as to the likelihood that someone will drop out, they vary across the individual services and they aren’t always foreseeable before someone has signed up, making early attrition tough to predict. That’s the conclusion of a Pentagon-funded study by Rand Corp. released in April, studying first-term attrition across the four DoD services from 2002 to 2013, totalling more than 2 million subjects.

“Ensuring force readiness requires the ability to identify recruits who are of sufficiently high quality and who will also fulfill the requirements of their first term of service,” James Marrone, the study’s author, wrote.

The cost of these early attritions ranges from about $200 million a year in the Navy to upwards of $400 million in the Army, when the cost of recruiting, enlistment bonuses, pay, housing and training are all figured in, according to the study.

Past research has shown some common factors in who tends to wash out, Marrone said, but no study had tried to use predictive calculations to verify them.

What he found is that while some characteristics ― such as sex, ethnicity, education and marital status ― were somewhat correlated with risk of washing out, the numbers were different across the services and likely had more to do with the events and circumstances of each individual’s service.

“In terms of differences across services, women are more likely to attrite in the Army than in the other three services; those without a high school diploma or equivalent are most likely to attrite in the Navy,” according to the report. “These differences highlight the potential importance of institution-specific characteristics, implying that personal characteristics may interact with institutional policy, peer groups, duties, or other aspects of military life and induce different rates of attrition in different services.”

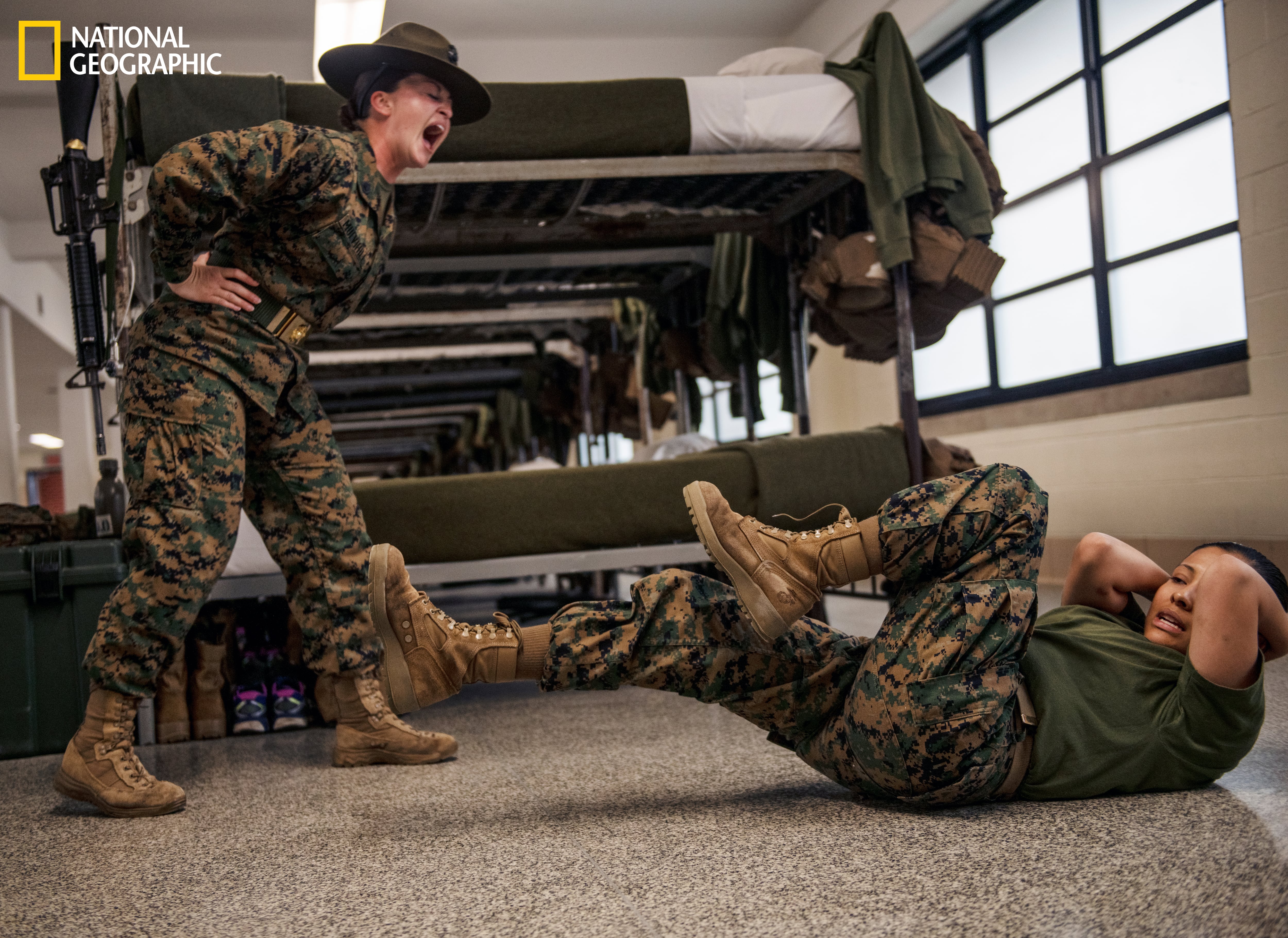

The study also took a special interest in first-term Marine Corps attrition, because at the time the data was collected, the service still segregated men and women in boot camp.

One reason used in the past to uphold this tradition is that all-female boot camp units helped build the women up, particularly their physical fitness, so that they were more on par with their male counterparts once they graduated.

Marrone found that this segreation didn’t affect their first-term attrition, however.

RELATED

“The Marine Corps does not stand out from the other services," he wrote. “In the first three months, across all services, women have a 1-to-3–percentage-point higher probability of attrition than males. In the first six months, the results across services start to disperse, but the marginal effect is still between 3 and 7 percentage points.”

The study also looked at other factors, including whether a recruit was married or if they needed a waiver because of unfavorable results of a background check.

In the first instance, the study found that “married recruits are more likely to attrite during the first 12 months, but those who make it past that point are less likely than other recruits to attrite later.”

In the other, it found that those waivered recruits “are no more likely than others to attrite during the first six months but are more likely to attrite after that time.”

In short, the report found that while there are some personal factors that could make a recruit more likely to wash out, there’s no accounting for how that will collide with their experiences in the military, making it difficult to predict whether experience will strengthen their resolve to serve or push them to a breaking point.

“This suggests that a major cause of attrition relates to factors that are either unobservable (or, at least, not currently recorded during the enlistment process) or occur after accession,” according to the report.

Marrone concluded that it’s “unlikely” that screening policies could accurately and cost-effectively predict this attrition from the get-go.

However, knowing that some of these personal characteristics can affect at what point a recruit washes out within their first term of service could help leadership zero in on when they might be most vulnerable.

“Based on what is known at accession, it may not be possible to predict with a high level of confidence that a given recruit will attrite, but it could be possible to predict their highest-risk period,” the report found.

It would also be worth further study, according to the report, to analyze how some of these predictive factors interact with a service member’s experience once they’ve completed initial training and reported to their first units, to see if there are particular jobs, duty stations, promotions, deployments or other circumstances that can affect the likelihood of washing out.

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.