During the first daytime airstrike of Desert Storm, Mark Fox flew out with about 30 airplanes that launched at once from an aircraft carrier, looking for the Scuds used to terrorize U.S. troops in Saudi Arabia.

It was a brilliantly blue day, sun glancing off sea and sand, and Fox flew alongside planes that would keep his F/A-18 Hornet—and the bombs he carried—safe.

“The tactics we used were pretty darn good,” said Fox, now a retired Navy vice admiral.

But the Iraqi pilots weren’t bad, either.

“We were a lot better trained, and we had better equipment,” Fox said. “But we respected them—there was no question about it.”

Fox had reason to. In the early hours of that day—Jan. 17, 1991— another pilot from Fox’s squadron, Capt. Michael Scott Speicher, had been shot down by an Iraqi warplane.

“I think it’s pretty certain that it was an Iraqi MiG-25 that shot him down that night,” Fox said. “And it was a pretty confusing melee in the air.”

Pretty quickly, Fox realized things would be rough all day.

“As we were going into Iraq, it was clear there were Iraqi air force airplanes airborne,” he said.

His group came in from south to north, and they had four F-14 Tomcats to handle any air-to-air threats. Prowlers flew alongside, with electronic countermeasures officers working to keep the Hornets safe.

High-speed anti-radiation missiles started coming in behind Fox and the other pilots and going over the top of their planes, looking for radar-equipped defense systems.

Fox had his bombs, but also air-to-air ordnance. The Tomcats did not have the benefit of the jamming aircraft, so they were flying tangentially, staying outside the missile engagement zone while providing a less-important target than the F-18s to the Iraqi radar operators on the ground.

“In the meantime, we’re coming straight up,” Fox said.

The E2 Hawkeye pilot—who flew high above for traffic control and to watch for problems—warned the jets they had company.

“Hey, they’re bandits!” Fox heard through his headset.

Known hostile.

The E2 guided the pilots with the use of a “bullseye”—that day, it was called “Manny,” and it was an airfield about 15 miles from the bigger air base, H3. Everyone flew relative to Manny, and that’s how the Hawkeye let the pilots know where the bandits were.

“‘Bandits, Manny, one-eight-five, 25 southbound,’” Fox said. “Which means, ‘OK, there are bandits—known bad guys—south of H3 northwest heading 25 miles.’”

Which meant they were close. But the pilots hadn’t trained much on the bullseye concept in the 1980s, Fox said. Instead, they had used their ship—referred to as “Zulu”—as the bullseye.

“So you’re doing this kind of mental math, this mental basketball, ‘OK, where are those guys?’” Fox said. “And it’s the first day of war. Pucker factor is pretty high.”

The Air War

People tend to remember Desert Storm as a short, easy war—and compared with the “forever” wars that followed, that makes sense: a 100-hour ground war blip in the annals of history.

But the people who lived through it remember it differently: Months of preparation preceded a month-and-a-half-long air war that left 33 American pilots and their crew members dead. Iraqi pilots had trained with Soviet pilots, as well as fighting in an eight-year war with Iran, leaving them better prepared to fight than anyone expected. And complications in the Middle East—from dust storms to pitch-black nights to unfamiliarity with unstudied territory—presented constant challenges.

The air war lasted from the day of Fox’s encounter with the bandits, Jan. 17, until Feb. 28, 1991, with coalition forces dropping 88,000 tons of munitions during more than 100,000 sorties. They decimated Saddam Hussein’s air force, bombing shelters Hussein thought would be impervious to attack. The pilots proved to Hussein that he couldn’t win in the air over Kuwait, took out key defenses and command-and-control centers, ensured troops on the ground wouldn’t be hit by enemy aircraft, and then supported the ground war from Feb. 24 until Feb. 28.

Without constant training, U.S. pilots say they would have accomplished none of that. But without the benefit of combat-experienced service members after years of peace, there was no one at the unit level to prepare them for the momentum of war, as well as the heartache that followed.

Hussein invaded Kuwait Aug. 2, 1990, and within days, President George H.W. Bush deployed U.S. troops, ultimately more than 500,000—including hundreds of pilots—to move into the Persian Gulf for a six-month build-up of a tank war built upon Cold War training for the Fulda Gap and an attack from the Soviets.

This was known as Desert Shield.

But as it turned out, the Iraqi military had been trained by and gained equipment from the Soviets, including an array of helicopters and jet fighters. Iraq had invaded Iran in 1980, using Soviet-era equipment, but as the country gained support in its fight against the Ayatollah Khomeini’s hardline government, the United States under President Ronald Reagan supported Hussein with money and equipment, such as howitzers and Huey helicopters, sold through Jordan and Saudi Arabia.

The Iran-Iraq war ended in a ceasefire negotiated by the United Nations Aug. 21, 1988.

Because of the United States’ involvement, the warfighters going into the Persian Gulf to fight Hussein had a pretty good idea of what they were up against—and they had trained against Soviet tactics for generations. Still, Iraq had the fourth-largest army in the world, and Iraqi pilots had years of combat experience.

And the Americans hadn’t trained for everything: Smoke from oil fires lit by Hussein grew so thick that the sun disappeared and pilots had a hard time seeing past the beaks of their planes. The sand hindered helicopter landings as it rose up in gritty, blinding clouds. And the Iraqi pilots turned out to be much more advanced than anyone expected—working in coordinated attacks to trick American pilots into dangerous airspace.

As Hussein missed the deadline to pull out of Kuwait, Desert Shield became Desert Storm on Jan. 16, 1991.

The United States set up hospital ships and field hospitals along the Iraqi-Saudi Arabia border in preparation for a blood bath. News reports stated military leaders expected 10,000 American deaths in the first week of battle—which is what the pilots and ground troops read in the copies of Stars and Stripes passed from person to person in the days before the Desert Storm started.

The war was historic: Iraq lost 259 aircraft, with 36 being shot down. The United States lost 63, with 33 to combat. And 148 Americans were killed in action, with another 145 losses to nonhostile actions, such as vehicle accidents.

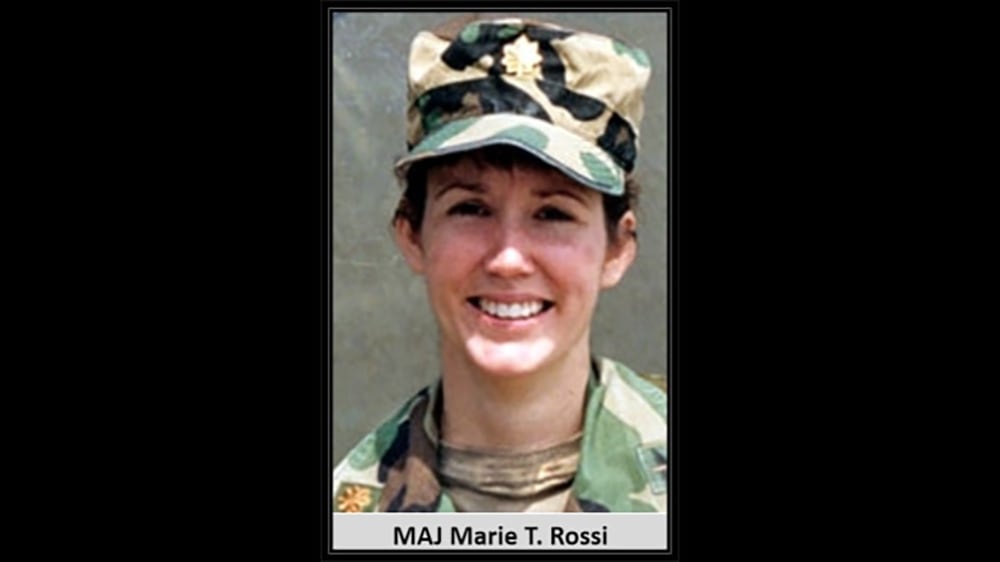

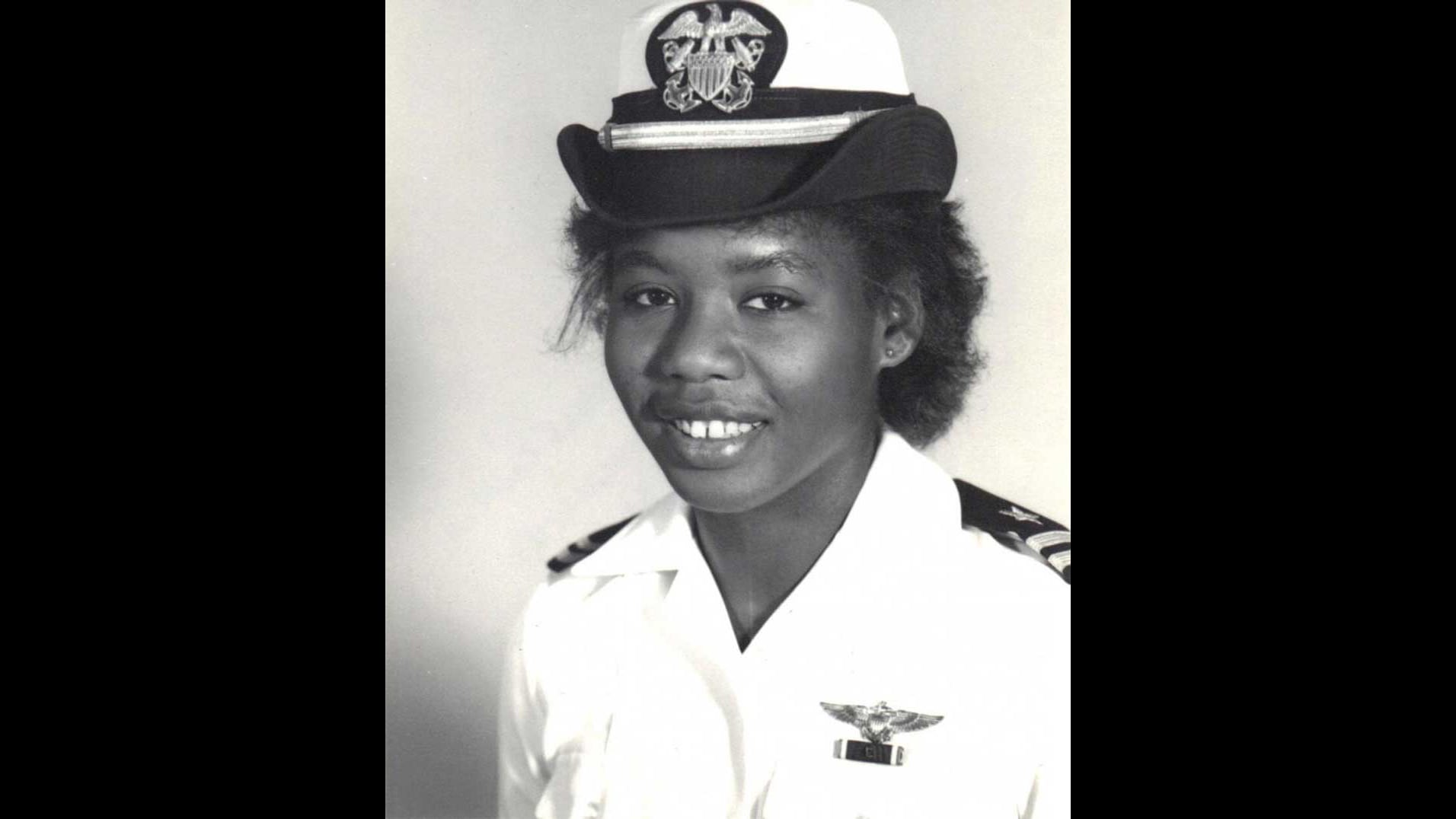

Maj. Marie Therese Rossi-Cayton was the first woman to serve as an aviation unit commander in combat, and she died in that role when her CH-47 Chinook hit an unlit microwave tower while she was flying at night on March 1, 1991, in Saudi Arabia. And Brenda Robinson, the first Black female Navy pilot, also flew in Desert Storm. She flew mail, passengers and cargo to aircraft carriers. The women who served in that war led, in part, to the 1993 lifting of the combat exclusion policy, which kept women from serving in combat roles.

Desert Storm also signaled the beginning of modern warfare for pilots, as the first stealth bombers were launched, GPS (sometimes) helped pilots make their way across landmarkless terrain, and smart bombs sought out targets if pilots could get them in the general vicinity.

Between 30,000 and 100,000 Iraqi fighters were killed, most during the air war, and an estimated 100,000 Iraqi civilians also died from wounds or lack of food and water, as well as medical supplies, because of the war.

Three pilots—an Army Kiowa helicopter pilot: Fred Wellman; an Air Force Thunderbird pilot: Cesar Rodriguez; and Fox—told The War Horse recently about their experiences 30 years ago this week, but spoke as if the battles they faced were yesterday. They talked about the missiles they launched, the friends they lost, the lessons they learned, and the personal battles they’ve fought in the years since.

All three said they never expected a desert war, and that they found themselves scared, ready, well-trained, and surprised by the skills of their opponents.

“I Will Not Return Unavenged”—58th Tactical Fighter Squadron, Air Force

Retired Air Force Col. Cesar Rodriguez had no idea he wanted to be a pilot. His father, a career Army officer who retired as a lieutenant colonel, had served in Vietnam, but he never talked about it, Rodriguez said. But Rodriguez learned through his father’s service to love traveling and the “personalities” he met, and he knew that he wanted to join the military.

“I didn’t have a passion to fly as a kid growing up,” he said. “I really literally fell into it.”

At the Citadel, a military college in South Carolina, Rodriguez took a series of tests to see what he might do well in—and his Air Force scores were high. He shifted out of the Army Reserve Officer Training Corps program and into the Air Force program, and he eventually qualified for flight school.

After the Citadel and at flight training, Rodriguez figured he’d never see more than a skirmish: There would be no World War III, and he would spend his career fighting the Cold War, which would consist of a dance to avoid war with the Soviet Union—which the Soviet Union also appeared to want to avoid.

“I thought that the ‘war of all wars’ had been fought, and the country would never be tested or reach out like the Vietnam era.”

In 1983, the Soviet Union shot down Korean Air Lines Flight 007, and Rodriguez flew his A-10 Warthog to the northern coast of Japan to look for bodies. That, he said, was when he realized just how real his mission was.

But while his service drove a need to understand both the news and the military’s role in it, he said he didn’t know much about the Middle East.

“I remember when we prepared for our combat missions certifications—our qual tests—all of our scenarios that were given to us by the Air Force and others were really all Cold War-Eastern European-type of approaches,” he said. “Nobody ever even thought we would be engaged in the Middle East. And lo and behold, that’s where we ended up going. Our squadron didn’t even have any maps of the Middle East.”

When they got the call to deploy, he was leading a detachment at a flying exercise at Gulfport, Mississippi. His eight F-15s flew against about 24 Missouri Air National Guard F-4E Phantom IIs. Because of new technology in the F-15s that the other pilots didn’t have, Rodriguez’s team was close to undefeatable.

“We took them all out,” he said. “It was a great week for us as a squadron, as a team—and that night was going to be one hell of a party.”

But when he landed, another officer killed his plans.

“Hey, Rico, party’s off,” the officer told him. “All your bags are being packed up. … I said, ‘OK, what’s going on?’ He says, ‘I don’t know.’ We just we were told, ‘Get home ASAP.’”

At that point, everyone started to check the news to see what they might be in for, he said. When they arrived back home at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida—the home of the 58th Tactical Fighter Squadron—the flight line was “bustling” with activity.

By the end of August, they were in Saudi Arabia. After they landed, they immediately put the jets on alert.

“We started flying missions, in what we called defensive counter-air missions, where certain assets were airborne—AWACs, AB-Triple-Cs, Rivit Joints, obviously, tankers, U2s—all those assets that were literally trying to start gathering data of the enemy, air and land orders of battle. They were in the air, so we were up there protecting them 24 hours after our jets landed.”

Because it was 1990, every day, Rodriguez’s air tasking order came on a floppy disk flown in by a Learjet. They had to print out the order.

Maps weren’t as big of an issue for his squadron because they flew high—at 30,000 or 40,000 feet, so they weren’t looking for landmarks.

And Rodriguez said that while he wasn’t familiar with the Middle East, he had been training—particularly during the two or three trips a year to Red Flag training at Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada—against exactly the weaponry of the Iraqis.

On the ground, intel worked hard to get the pilots what they needed.

“Everybody used every resource available to us to help us build situational awareness of what could be up there,” he said. “As well as what were the real current Russian capabilities that were there, to include knowing that at some point, we could also be fighting against Russian pilots. So we planned for the worst. And then planned again on top of that.”

The Iraqi pilots also surprised him.

“I would say first and foremost, that I’m pretty sure that they all woke up 100% committed to defending their nation,” he said.

And some of them knew how to do their jobs well and had proved it in the war against Iran, but with the training Rodriguez’s team had had, “I’ll just say it bluntly: We would have kicked anybody’s butt,” he said.

He was confident about his team, and he was confident about his own flying abilities, but each new experience in combat proved different from anything he had done in peacetime.

“Once everybody disconnected from my com system, and it was just me inside the cockpit … when I was in my quiet zone, I was—I’ll just use the term bluntly—I was scared shitless,” he said. “Because you don’t know. You don’t know if there’s going to be another guy or gal on the other side who has prepared harder than I did. You don’t know if there’s the lucky BB, the lucky bullet. I’ve seen and I have good friends who died in peacetime. Well, here we are going into combat. And that can happen to you too. So yeah, ‘scared’ was a part of my ritual.”

But he remembered the everyday rituals that apply in peacetime and combat, and he used them to calm himself. And, he trusted his training.

Jan. 19, three days after the air war began Baghdad-time, would prove to be the test.

Rodriguez and his team flew out on a defensive counter-air mission to protect U.S. Intelligence assets south of the Iraq border at high noon on another clear blue day. It was almost blindingly bright.

“And then a new target popped up that had not been identified before,” he said. “So the airplanes that were on alert status on different bases around the region came together, and we went and attacked this particular target.”

They found themselves flying 60 or 70 miles southwest of Baghdad. The Iraqis, using pilots as well as integrated air defense systems and missile defenses, tried to defeat the alliance pilots, but, “We were able to neutralize that piece of it,” he said.

But then the situation changed significantly as experienced Iraqi pilots tried to draw Rodriguez and his wingman, Craig “Mole” Underhill, into a trap.

“My wingman and I engaged two MiG-29s that were using a highly sophisticated tactic to both attack us, and then also lure us into running into their integrated air missile defenses,” Rodriguez said. “So, a complex tactic that many would have probably said, ‘Now, there’s no way they could do that.’ And then, oh by the way, on the 19th of January, they’re doing it.”

At the time, the two pilots didn’t understand the additional danger—they simply took on the MiGs.

“My wingman shot down one of them with an AIM-7 Sparrow”—a radar-homing air-to-air missile—”and the other one, I was in a visual maneuvering dogfight”—a close-range, one-on-one air battle—”with him, and it forced him to execute his last maneuver into a ‘split S’”—as he flew away from Rodriguez, the Iraqi pilot, Captain Jameel Sayhood, rolled upside down, pointed his nose to the ground, and tried to level out to come back at Rodriguez, but he was too low—”which basically caused him to crash into the ground.”

During their debrief, the two American pilots learned that it had been a coordinated attack, designed to bring them into the Iraqi integrated air missile defenses.

Because of their training, because of the thousands of times they had performed the same maneuvers in peacetime practice sessions, they had completed their mission “pretty much flawlessly.”

It was the third day and Rodriguez’s sixth sortie. But he wasn’t done yet. During those days, he slept as close to his jet as he could because he didn’t want to waste any time driving from place to place when he could catch extra sleep. He barely ate.

“It was just grinding, day in and day out,” he said.

On Jan. 26, he prepared for another daytime mission, but this time, sand storms rolled across the northern border area between Saudi Arabia and Iraq. When the sandstorms didn’t force grit into every surface, thunderstorms took over. Rodriguez and his squadron flew in and out of clouds all day, and they found themselves in bad weather as they formed for an engagement.

They made their way to the threat, but they also searched for clear skies, eventually working down from 35,000 feet to about 15,000 feet, in and out of thunderstorms and clouds and rainstorms.

“Once we got below 17 or 18,000 feet, it was just rain down below us—it was pretty easy to see,” Rodriguez said.

Capt. Rhory “Hoser” Draeger served as the flight lead on that mission, and Capt. Bruce Till served as his wingman. Both Rodriguez and Draeger had one air-to-air kill as they headed out.

“‘You know, you and Rhory sounded eerily calm,’” Rodriguez recalled that Till said. “And I was scared to bejesus in my cockpit.”

As they monitored the west side of Baghdad, the F-15s went up against three MiG-23 Floggers coming out of the airfields to the west.

“It appeared they wanted either to get into Baghdad or fly into Iran,” Rodriguez said. “We don’t know what their flight plan was really telling them to do. … But if I had to go through a flight of four F-15s to get to my next either refueling station or my next dinner, I would kind of reach down and kiss my ass goodbye.”

At about 11 or 12 miles out, they could see the MiGs, and they hit them with AIM Sparrow missiles.

“Whether they knew to be looking for us, or they could see us, I don’t know that one,” he said.

After a mission in Kosovo, Rodriguez would be one of three pilots to get three air-to-air hits—the most hits since the Vietnam War.

After that day, his squadron had several more kills, even as the air war drew down at the end of January.

“I guess in the vernacular of air-to-air squadrons, we were the lucky ones,” Rodriguez said. “We had the highest number of air-to-air kills in the war for everybody. We had the highest number of pilots with multiple kills. And we were the smallest squadron as far as number of airplanes in the air campaign.”

He attributes their success, including a “98.9% launch rate for every mission that we were tasked to support,” to the people on the ground making sure he could fly—everyone from mechanics to cooks.

As the ground troops were set to roll in, pilots started to receive intelligence about the booby traps Hussein had placed just about everywhere—from ship mines in the Persian Gulf to the tank and toe-popper mines laid for the ground troops. On a mission, he saw canals that had been filled with oil that Hussein planned to ignite—the Saddam Line, which would need to be blown up with incendiary bombs dropped by C-130s.

“And then, of course, we started to see the desert on fire,” he said, referring to the oil wells Hussein had set aflame. “From the sky, the answer is, ‘It sure sucks to be down there.’”

As the air war turned into the ground war and the pilots moved into more of a support role, Rodriguez knew the battle was just beginning.

“It was very clear from my chair at 30 and 40,000 feet looking down,” he said. “This is not over.”

“First to Fight”—24th Infantry Division (Mechanized), Army

Retired Army Lt. Col. Fred Wellman had wanted to be anywhere but a heavy mechanized division. He wanted action, and Panama, Libya, and Granada had all been skirmishes that had no time for tanks.

Instead, as a 23-year-old lieutenant, he led a scout platoon of Bell OH-58 Kiowa helicopters in an Apache battalion in the 24th Infantry Battalion (Mechanized).

“I remember actually getting into a discussion with my battalion commander, when I first got assigned to the Apache battalion, saying that I needed to get out of there and get to a light infantry battalion like 7th ID because no, we’re never going to have a tank war again,” Wellman told The War Horse. “You gotta love the hubris of a lieutenant from West Point: I was that guy.”

Three platoons in, Wellman was champing at the bit.

“He must look back and think, ‘What a fucking idiot,’” Wellman said, laughing. “We didn’t really envision a huge set-piece tank war in the Middle East.”

Wellman’s father had served in the Marines during World War II; he lost one uncle with the Marines in Korea, and a second was an Air Force pilot who died when his bomber crashed. With that background, Wellman knew he wanted to serve and applied to West Point. Like many of that generation, he worried that he’d never get a chance to prove himself.

He had been stationed in Fort Stewart living in an apartment by the airfield when Panama went down a year before Desert Storm, and he could hear the Rangers flying out.

But in August 1990, he got a call to come into work in the middle of the night.

“Well, the rest is history,” he said.

His fiancée had just moved down from New York, and they were moving into a new apartment together, so they didn’t have cable yet. He went to another lieutenant’s apartment to watch TV and hang out.

Hussein invaded Kuwait.

“[My friend] and I were sitting on the floor, drinking a beer, and we look at each other,” Wellman said. “I said, ‘You know, man, all our shit’s painted tan.’”

They had just returned from desert training at the National Training Center.

“‘You don’t think they’d send us?’” Wellman remembered saying. “Because the joke used to be that we’re part of the rapid deployment force, which is the 18th Airborne Corps. But we’re the not-so-rapid deployment force, right? It’s a mechanized division. It’s not like you can throw us on some C5s.”

Wellman served as acting commander that week because his commander was on leave, and he got called into battalion at one in the morning.

“‘Y’all aren’t going to believe this, but we’re fucking going,’” Wellman recalled his battalion commander saying. “‘We’re, no shit. We’re deploying to Kuwait, to Saudi Arabia.’”

Back then, there was no family readiness group, and girlfriends and boyfriends didn’t count when it came time for benefits and important notifications, so he and his fiancée took their lunch hour to get married Aug. 9.

The next week, the unit loaded their equipment on ships and headed out.

Wellman had been promoted to platoon leader of a scout helicopter platoon in Alpha Company, part of a battalion that had just transitioned to alpha-model Apaches.

Each Apache company had six Apache helicopters in a gun platoon, and then one platoon of scout helicopters—the OH-58 Kiowas. One or two scouts flew with three or four Apaches.

Not only were they heading into a tank war, but the Apaches operated like tanks—even flying in tank formation. And they were used just like tanks: to take out tanks. But the Kiowas are small, fast two-seater birds, so they acted as the Apaches’ eyes, flitting in and out to scout the landscape.

“Barry McCaffrey was the division commander and really wanted his Apaches forward,” Wellman said. Other brigades put their Apaches on airfields, but Wellman’s unit headed out to the desert and set up tents.

“We lived in the desert the whole time, which brought its challenges, but it did prepare us well for the invasion,” he said. “We had to be ingenious, like, how do you land without any dusting out?”

Over time and multiple landings, the sand turned to “moon powder,” so the pilots wet it down with water. That lasted about a minute with August temperatures zooming into the 100s. So they used oil. Finally, the Army brought in a synthetic substance that hardened into pavement.

They arrived just behind the 82nd Airborne as part of the first wave. At that time, they believed Hussein would attack Saudi Arabia, so Wellman’s scouts helped with the war planning—going out with maps and binoculars and reporting back.

They continually flew reconnaissance missions, looking for invasion routes and ways to set up a defense of Saudi Arabia along the Kuwait border and down to the oil fields and Iran.

When it became obvious Hussein wasn’t going to chance it, they began to plan the attack.

“We’re in MOPP suits and training, but we flew a lot,” Wellman said. “We worked those aircraft hard. From the battalion commander down to the company commander, it was just like train, train, train, train. It’s like all the time, so it became rote.”

They had so much touch time that they achieved a level of communication rare for any team of pilots.

“We were able to fly our Apaches without talking,” Wellman said.

They also flew support—running liaison, picking up packages, running passengers to the airfield.

“Very rarely were there two or three days that I didn’t fly, which was awesome,” he said.

Every morning, they would clear the weapons training range because Bedouins would wander in at night.

As the air war kicked off, Wellman worked to cover the ground-troop movements as they positioned themselves for battle.

“One of the reasons we took a month to do the air war was to soften them up,” he said. “But also, we got two corps or three corps of troops in position undercover.”

His unit moved up to the Iraqi border to the west, where they remained on the far left side of the big left hook—the coalition’s left flank and west of Kuwait—of the original battle plan. After they got settled out front, they started to fly again.

“I would do a lot of rides, pop over the border because the cavalry would say, ‘Hey, there’s some Iraqis poking around,’ and check it out,” Wellman said. “So we were trying to cover our movements, so we would send the Apaches up there, but as the war progressed, General McCaffrey was really dissatisfied with the intelligence he was getting about our invasion routes.”

Beyond what they heard at headquarters, the pilots generally didn’t know about the events of the war. In 1991, they had no individual access to satellite phones or television, and very few people, in general, had heard of email.

“It was different than [Iraq]”—where Wellman deployed after 9/11—”where you could pick up satellite. We’d go to battalion headquarters trying to get updates because they had the TV going up there. But at the company level, you’re pretty much in the dark. People forget how old-school it was.”

And at that point, no one had combat experience at the company level, either.

“Combat patches were a very rare thing in 1990—just the old Vietnam guys and maybe a few Panama vets,” he said. “You got a lot of people green behind the ears going into combat. It was exhilarating. It was terrifying.”

Looking back, he said he made a lot of mistakes.

“I was very stressed out,” he said. “I remember being very short-tempered. Now I know that I was like, really wired. I look back at my own experience as a young lieutenant and I’m like, ‘God, you sucked.’ Like, ‘Jesus, what an ass!’”

He laughs about it now, but he took those lessons into future deployments, realizing he needed to keep his soldiers calm and to understand what they were going through: Stick to the training and muscle memory. Their brains are frazzled; they’re losing friends:

Don’t get distracted. Be calm and focused.

“You always have to fly the helicopter,” he said. “It just takes a slight twitch and people die.”

As the air war continued into February, Wellman’s unit became more important.

They flew with black-and-white maps—photocopies of maps—because the Army didn’t have enough maps of the Middle East. He highlighted the Tigris River with a light-blue marker.

“So [McCaffrey] decided he wanted to fly Apaches into Iraq along the air routes at night—the invasion routes—to do route reconnaissance,” Wellman said. “But the joke was that Apaches couldn’t navigate: Their job was to blow shit up. Apache pilots had notoriously bad navigation.”

No one wanted to send the pilots in on infrared—the Apaches used infrared, and the scouts used night-vision goggles.

“You know it was darker than a witch’s ass in Iraq,” he said. “I had a close call myself on a night where it was just blacked out and I couldn’t see shit.”

But as he headed toward the ground, he saw his red taillights mark the sand.

“So it was dangerous flying with NVGs,” he said. At night, “We would fly next to the Apache instead of leading it.”

The Apache cockpits were filled with red lights. The Scouts used the cockpit lights to make sure they didn’t run into their fellow pilots.

“It was pretty hair-raising,” Wellman said.

The Apaches, without guidance from their scouts’ Kiowas, struggled to find their routes.

“A couple of us scout platoon leaders and pilots went to our leadership and said, ‘You gotta let us go in—you gotta let us fly these missions,’” Wellman recalled. “We were just sitting there, and it was killing us.”

They agreed. They planned to send in two scout weapons teams, with Wellman and Spc. Chris Anderson—his aerial observer—going out. But then, because Wellman was the most junior pilot on the team, the other pilots asked him to “pause mission.” Wellman was not happy, but he regrouped.

As the platoon leader, he had the most administrative rank: He made the decisions. But as a pilot, the chief warrant officers—technical experts who often have time as enlisted service members before they commission—were older and had more time in the cockpit than Wellman did.

“This is not about leadership or rank,’” he said. “‘This is about who’s going to safely fly in another country where there’s zero information and come back.’”

Wellman gave the OK, and they replaced him with CW2 Hal Reichle—a more experienced pilot—and Spec. Mike Daniels. CW2 Dennis Midgley would also go out, as originally planned, with his left-seater, Spec. Dave Corlette.

That night, Feb. 20, “Hal went up with one team of Apaches, and Dennis went with another and they did the routes,” Wellman said. “At some point, they hit what was apparently ground fog up in Iraq, and the aircrews became separated. And the Apache did an abort mission and came back, and when they returned across the border, Hal and Mike weren’t with them.”

The next morning, another company of Apaches and a Blackhawk found them: They had crashed about four kilometers into Iraq. They had been killed when they hit the ground.

“Years and years and years of therapy for that one,” Wellman said, describing his survivor’s guilt at having lost not only two of his guys, but also someone who went out in his place.

“We did a couple more missions of the same kind where the Iraqis kind of poked the border and we’d go after them,” Wellman said. “And then that was it until the ground war kicked off and we did our thing.”

“Anytime, Anyplace”—Strike Fighter Squadron 81, Navy

“As far back as I can remember, I wanted to fly airplanes,” said Fox, the naval aviator. “And when I found out that there were airplanes that landed and took off from ships, that just sealed it for me.”

Considering that he grew up in West Texas and didn’t see the ocean until he went to the Naval Academy, this seems particularly prescient. His dad was a doctor, but he had been on aircraft carriers during World War II. “That may have given me a little taste of it,” Fox said.

Fox earned his commission in 1978—during the post-Vietnam “doldrums.” He was there for the soul-searching that followed that war, and then for Ronald Reagan’s build-up of the forces in the 1980s.

“I was always anticipating that there would be some sort of dust-up with the Soviets,” he said. “And you know, that didn’t work out.”

He started his military career on the A-7, but then transitioned to the FA-18 Hornet in 1984 before serving on the USS Cole in the Mediterranean Sea.

“Marvelous,” he said. “It’s just a magnificent airplane. It’s maneuverable and reliable and all the things that—it’s a marvelous jet. And everybody in the Med wanted to bump heads with us. So we wound up in exercises fighting British F-4s and Italian F-104s.”

While he was deployed, in 1986, the United States launched airstrikes against Libya in retaliation for sponsorship of terrorist attacks against Americans. More than 100 U.S. Navy and Air Force planes hit five targets within the space of an hour. But it was still different from Desert Storm.

“I’ve been on the edge of my seat,” he said. “I’ve been in crisis before. But this was the first time that I ever expended ordnance in personal combat experience.”

Fox was a lieutenant commander in 1990, and he commanded an F/A-18 Hornet squadron. They’d been training for the Cold War, as usual.

In early August of 1990, his ship, the USS Saratoga, deployed immediately when Hussein invaded Kuwait.

“We didn’t know it, but it was the end of the Cold War,” Fox said. “The whole geostrategic balance was kind of shifting there a bit, and Saddam just had the incredibly bad timing to decide to invade Kuwait at the same time that we were kind of at the peak of our Cold War strength, anticipating something against the Soviets.”

The Saratoga “hustled over” to the Persian Gulf without having any playbook for action in the Middle East.

While he felt prepared for the Iraqi defenses, he found the prospect sobering.

“These guys have the third- or fourth-largest army in the world, and they’re battle-hardened,” he said. “They’ve been in the Iran-Iraq war for almost the entire ’80s. And there were all these predictions that ‘the desert was going to swim in blood.’”

When he first arrived in Saudi Arabia soon after Hussein attacked Kuwait, he spent his time trying to figure out the battle plan: How do we support the B-52s? What do we do if Hussein invades Saudi Arabia? Maybe we’ll be doing a battlefield interdiction against the tanks.

And then Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf Jr. and Maj. Gen. Chuck Horner came into the picture. “There was a shifting in our thinking from reactive and defensive to proactive and offensive, if you will, going into this, with the backdrop of the UN negotiations and the UN Security Council resolution.”

Hussein was told he needed to remove his forces from Kuwait by Jan. 15, 1991—or else.

“As we got closer and closer, it became more and more obvious that he wasn’t going to leave,” Fox said. “I always thought that he would somehow figure out a way to finagle it and wiggle out of it somehow. He blew it.”

As they prepared, they practiced with mirror-image flights: The ship would launch the airplanes with the loads they would use in combat. The pilots would fly the same distances they would have to fly in war. And they would replicate the same procedures they would use to get to the Air Force tankers. That meant four-and-a-half- to five-hour sorties—considered long in the days before the global war on terror—and making sure all the other parts fit together.

The Navy carriers didn’t have tankers on board, and the Air Force tankers worked differently from the Navy’s, which meant the pilots needed adapters, which were created just for Desert Storm—and lots of practice.

At the same time, they studied Iraq’s systems and defenses to try to figure out how to “crack” them.

“They had a pretty sophisticated integrated air defense,” he said. “How do you take that apart? Well, you kill the sensors. And you kill the long-range radars. And then you start to work your way so that you’re blinding them or you’re jamming them.”

And then the war began with the “Great Scud Hunt” of 1991.

Iraq’s Scud B tactical ballistic missiles terrorized troops based in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, beginning the night of Jan. 17, sending them into MOPP-4 protective gear. The Scud was shot down by a Patriot missile. Another Scud was launched against Israel, and strikes continued in the following days against both countries, ultimately killing 31 people. In February, a Scud would kill 27 more people: American reservists from Pennsylvania.

The U.S. forces hit 28 fixed Scud sites with everything from B-52s to F-117 Stealth Fighters the evening of Jan. 17, 1991. Then, they went after “Scud trucks”—trucks from which Scuds could be launched and that were scattered throughout western and southern Iraq. The coalition went after them with A-10 Thunderbolts, RAF Tornado fighter bombers—and F-18s.

“That was a dynamic targeting problem that we hadn’t really ever trained to,” Fox said. “It’s a hard one.”

That day, January 17, Fox flew without knowing what had happened to Speicher—the pilot who had crashed early that morning after taking off from the Saratoga. Speicher would be the only American still missing in action at the end of the war. Rumors would persist for years that the pilot had ejected as his jet crashed early that morning. He had not. Years later, in 2009, an Iraqi told U.S. Marines the Iraqi had witnessed Bedouins quickly bury Speicher’s remains. Iraqis then led Marines to the site, and the pilot was returned home. The CIA reported he had died on impact.

Fox’s target was in an airfield called H3. The F18 jets flew in along the EA-6B Prowlers, which jammed electronic signals from the Iraqi integrated air defense system so the Iraqis could not find them.

“The Tomcats are up north as a target, and I’m hearing these calls about the bandits,” Fox said. “And finally, the E2 guys make this dynamite call, because we were in a group that was headed right at them, and they were headed right for us.”

Fox and the other pilots moved in quickly toward the target, and Fox was about to drop his bombs.

“The E2 said, ‘Those bandits are on your nose 15 to 30 miles,’ and we’re about 30 miles south of the target at this point,” Fox said. The F/A-18s were flying at about 30,000 feet, going “as fast as you can make a Hornet go without using afterburner.”

Everyone had three 2,000-pound bombs—three Mk-84s.

“It was a very heavily defended airfield,” Fox said.

Fox had an extra 2,000-pound bomb. He had Sidewinder missiles on his wingtips and two Sparrow missiles.

“The E2 says, ‘That bandit’s on your nose at 15,’” Fox said. “I immediately was looking low. We had mechanically scanned radars in the bay, and so my look assignment was to look low.”

He put the Sidewinder into quick-lock acquisition mode. He put a lock on the Iraqi MiG at nine miles.

“It takes a lot longer to just say this than it actually happened,” Fox said.

The E2 came back. “On your nose at 15.”

Boom.

“Lock, there’s a guy at nine miles, he’s at Mach 1.3,” Fox said. “So he’s over supersonic. I’m at .9 Mach or .91, so I’m close to supersonic, but I’m not supersonic.”

That’s two airplanes closing at a combined rate at Mach 2.2 or 2.3.

“Things are happening pretty fast, I guess is the way to put that,” Fox said. “And what you train to in peacetime is what you do in combat.”

Inside 10 miles, five miles deep.

“I keep telling the Sidewinder, ‘Look down the radar line of sight,’ and he didn’t see anything,” Fox said. “‘Look down the radar line of sight.’ ‘We didn’t see anything.’ The third time I did it, I get the rar-rar-rar-rar-rar”—Fox made a noise like a vibrating spring.

Good tone: He knew he had a shot lined up. At the same time, he worked to stay ahead of the enemy plane.

“I knew he was a bad guy,” Fox said. “So I took a Sidewinder shot, ‘Fox Two’”—Fox Two is the radio call when a pilot fires a heat-seeking missile—and the missile came off the rail.

But then the uncertainty set in.

“Normally, it was like a train going by,” he said. “It’s like ‘Whoosh!’ But then it just disappeared.”

No whoosh.

Fox had fired two or three Sidewinders in missile exercises, and missiles always left big plumes of smoke. Shooting a simulator, he had experienced the same thing.

But as he fired at the MiG, he didn’t see a plume of smoke.

“It turned out these A-9 Mikes had brand-spanking-new smokeless motors,” he said.

No whoosh. No smoke.

“I thought, ‘Man, you know, it is the first day of hunting season—I may have buck fever,’” he said.

So he selected a Sparrow, a radar-guided missile, and fired a 4.2-mile barrel shot.

“Just as I squeeze the trigger on the Sparrow, the Sidewinder hit him, so there’s a big explosion,” Fox said. “But then out of the explosion comes a burning MiG-21, and then the Sparrow hit him, so he’d eaten two missiles.”

When the MiG went underneath Fox at less than 1,000 feet distance, the canopy was still on the jet. The airplane burned from mid-fuselage to aft.

“I didn’t call my shot,” he said. “I was so intent on what I was doing, I didn’t let the other people on the flight know.”

His wingman on the far left took on a second MiG-21.

“Splash one!” came in on the radio. Target hit with expended ammunition.

“Then the guy on my right very calmly says, ‘Splash two,’” he said.

Fox figured the first MiG explosion came from the other pilot, Capt. Nick “Mongo” Mongillo.

As they got closer to their target, they encountered more aircraft, moving slowly. The American pilots didn’t know if they were enemy planes, but they were making unusual mistakes, as if inviting the Americans to come at them.

“Some of the intel that we had studied, before the war started, was the Iraqis during the Iran-Iraq war would do some pretty sophisticated bait-and-drag kind of tactics, where they’d have somebody come up and do something really stupid,” Fox said. “And the Iranian F-4s would commit on that, take advantage of that mistake, and then the Iraqis would have a supersonic Flogger, or somebody going from low to high and come in there and nail the Iranians.”

He kept watch behind him to make sure he wasn’t being baited.

And then he realized he was on the target, and he would have to fly past it to pursue the other pilot with 8,000 pounds’ worth of bombs.

“He is no threat to me, and I came here to drop bombs,” Fox said. So that’s what he did. At H3, he looked for the command and control bunker that was meant to be his target, but it was noon—no shadows and no definition on the target. He couldn’t see it. But then he saw the secondary target, a big hangar. He dropped his bombs.

As he flew back, he wondered if perhaps the first explosion was his Sidewinder. He felt the excitement of the possibility, but he needed to focus on landing his aircraft on the carrier.

“I’ve got this kind of little angel and little devil on the shoulder,” he said. “You got a MiG kill!’ ‘You’re going to bolter!”

If a pilot misses the wires on a ship landing and has to come back around to land, it’s called a “bolter.” And it’s embarrassing.

Because they’d lost a pilot early that morning, Fox said he wasn’t in any mood to do a victory roll or something dramatic to celebrate. He landed on his first pass—no bolter—and went to debrief.

Joe Mobley, a pilot who had been a POW during the Vietnam War after his plane was shot down and was an “absolute prince of a man,” looked at Fox’s tape.

Unknown to Fox, his first missile saw the MiG and went after him. Both the Sparrow and the Sidewinder had hit the back half of the Iraqi pilot’s plane.

“‘Mark, you fired a Sparrow into a burning MiG,’” Mobley told Fox. “‘Those are expensive, you know.’”

“‘I just wanted to be sure,’” Fox said, laughing.

“How well you train is a direct indicator of how well you will fight,” Fox said. “There’s nothing really magical about that, except for the fact that you don’t know until you actually release ordnance in anger, and then you realize, ‘My training has been very good.’”

It was the first of only two U.S. Navy MiG kills during Desert Storm.

“The ship’s food tasted better. The sun shone brighter. It was just good to be alive.”

Kelly Kennedy is the Managing Editor for The War Horse. Kelly is a bestselling author and award-winning journalist who served in the U.S. Army from 1987 to 1993, including tours in the Middle East during Desert Storm, and in Mogadishu, Somalia. She has worked as a health policy reporter for USA TODAY, spent five years covering military health at Military Times, and is the author of “They Fought for Each Other: The Triumph and Tragedy of the Hardest Hit Unit in Iraq,” and the co-author of “Fight Like a Girl: The Truth About How Female Marines are Trained,” with Kate Germano. As a journalist, she was embedded in both Iraq and Afghanistan. She is the only U.S. female journalist to both serve in combat and cover it as a civilian journalist, and she is the first female president of Military Reporters and Editors.

Editors Note: This article first appeared on The War Horse, an award-winning nonprofit news organization educating the public on military service. Subscribe to their newsletter