WASHINGTON — Former Secretary of State George P. Shultz, a titan of American academia, business and diplomacy who spent most of the 1980s trying to improve Cold War relations with the Soviet Union and forging a course for peace in the Middle East, has died. He was 100.

Schultz died Saturday at his home on the campus of Stanford University, where he was a distinguished fellow at the Hoover Institution, a think tank, and professor emeritus at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business.

The Hoover Institution announced Schultz’s death on Sunday. A cause of death was not provided.

A lifelong Republican, Shultz held three major Cabinet positions in GOP administrations during a lengthy career of public service.

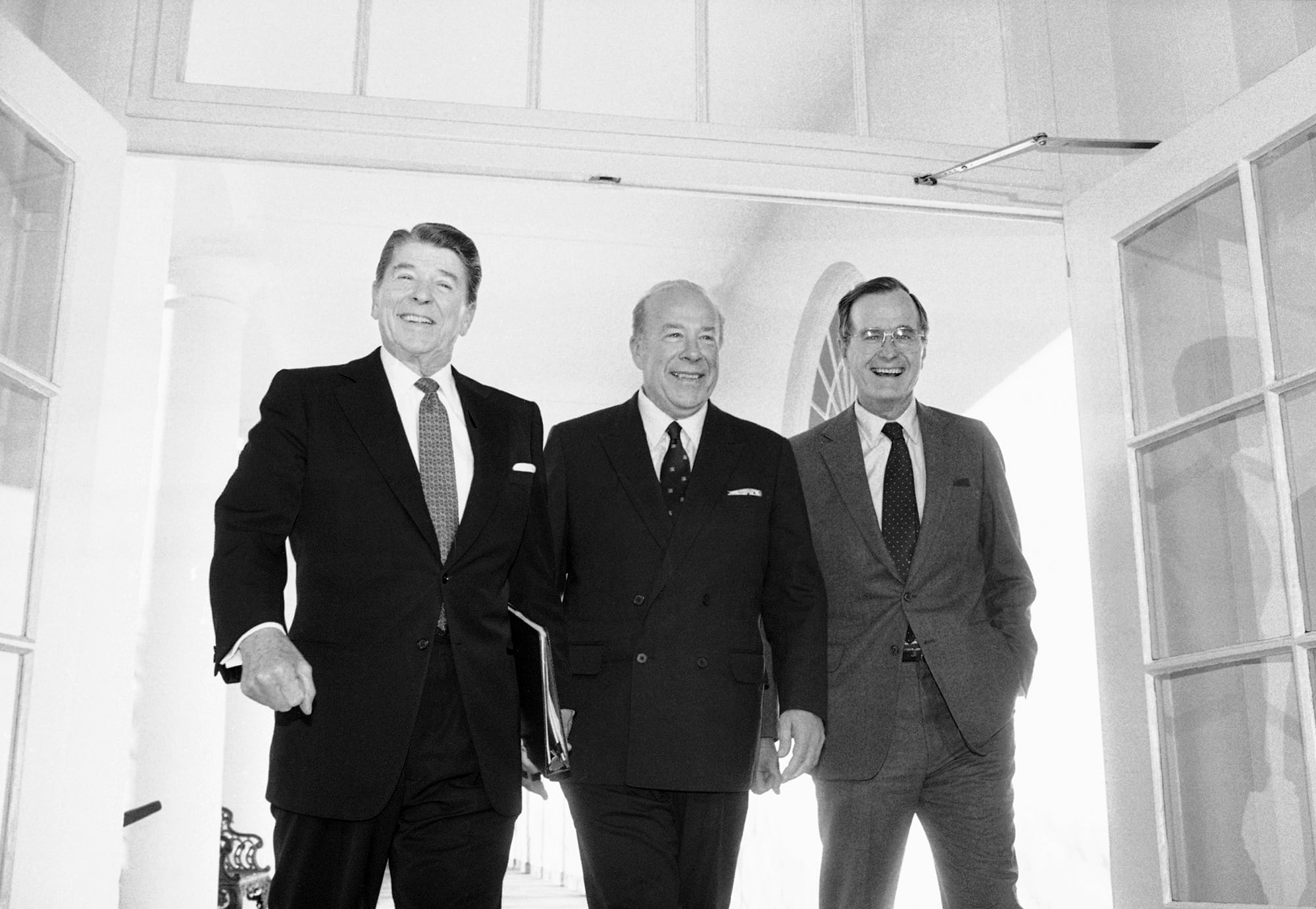

He was labor secretary, treasury secretary and director of the Office of Management and Budget under President Richard M. Nixon before spending more than six years as President Ronald Reagan’s secretary of state.

Schultz was the longest serving secretary of state since World War II and had been the oldest surviving former Cabinet member of any administration.

Condoleezza Rice, also a former secretary of state and current director of the Hoover Institution, praised Schultz as a “great American statesman” and a “true patriot.”

“He will be remembered in history as a man who made the world a better place,” she said in statement.

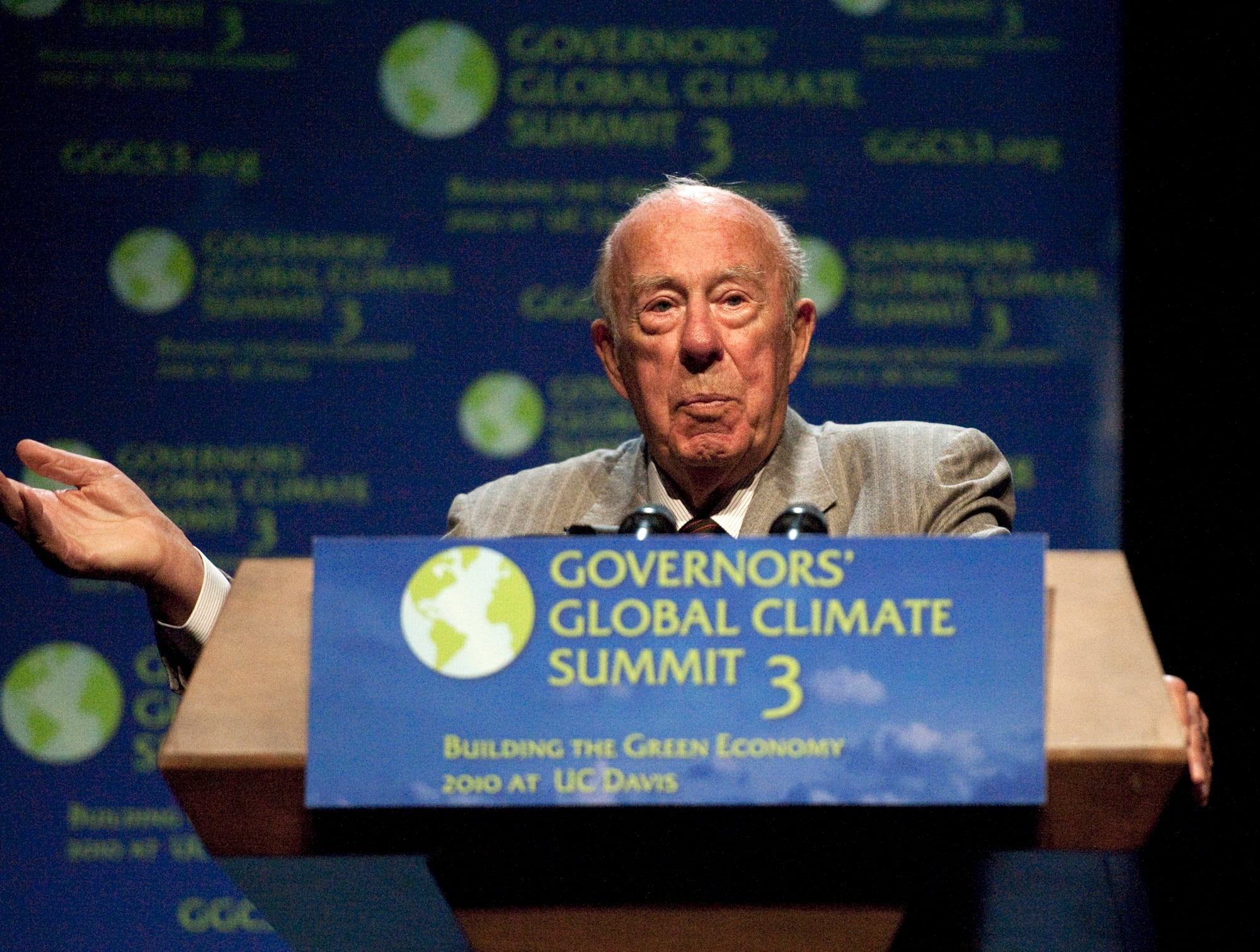

Shultz had largely stayed out of politics since his retirement, but had been an advocate for an increased focus on climate change. He marked his 100th birthday in December by extolling the virtues of trust and bipartisanship in politics and other endeavors in a piece he wrote for The Washington Post.

Coming amid the acrimony that followed the November presidential election, Shultz’s call for decency and respect for opposing views struck many as an appeal for the country to shun the political vitriol of the Trump years.

“Trust is the coin of the realm,” Shultz wrote. “When trust was in the room, whatever room that was — the family room, the schoolroom, the locker room, the office room, the government room or the military room — good things happened. When trust was not in the room, good things did not happen. Everything else is details.”

Over his lifetime, Shultz succeeded in the worlds of academia, public service and corporate America, and was widely respected by his peers from both political parties.

After the October 1983 bombing of the Marine barracks in Beirut that killed 241 troops, Shultz worked tirelessly to end Lebanon’s brutal civil war in the 1980s. He spent countless hours of shuttle diplomacy between Mideast capitals trying to secure the withdrawal of Israeli forces there.

The experience led him to believe that stability in the region could only be assured with a settlement to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and he set about on an ambitious but ultimately unsuccessful mission to bring the parties to the negotiating table.

Although Shultz fell short of his goal to put the Palestine Liberation Organization and Israel on a course to a peace agreement, he shaped the path for future administrations’ Mideast efforts by legitimizing the Palestinians as a people with valid aspirations and a valid stake in determining their future.

As the nation’s chief diplomat, Shultz negotiated the first-ever treaty to reduce the size of the Soviet Union’s ground-based nuclear arsenals despite fierce objections from Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev to Reagan’s “Strategic Defense Initiative” or Star Wars.

The 1987 Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty was a historic attempt to begin to reverse the nuclear arms race, a goal he never abandoned in private life.

“Now that we know so much about these weapons and their power,” Shultz said in an interview in 2008, “they’re almost weapons that we wouldn’t use, so I think we would be better off without them.”

Former Secretary of State Henry A. Kissinger, reflecting in his memoirs on the “highly analytic, calm and unselfish Shultz,” paid Shultz an exceptional compliment in his diary: “If I could choose one American to whom I would entrust the nation’s fate in a crisis, it would be George Shultz.”

George Pratt Shultz was born Dec. 13, 1920, in New York City and raised in Englewood, New Jersey. He studied economics and public and international affairs at Princeton University, graduating in 1942. His affinity for Princeton prompted him to have the school’s mascot, a tiger, tattooed on his posterior, a fact confirmed to reporters decades later by his wife aboard a plane taking them to China.

At Shultz’s 90th birthday party, his successor as secretary of state, James Baker, joked that he would do anything for Shultz “except kiss the tiger.” After Princeton, Shultz joined the Marine Corps and rose to the rank of captain as an artillery officer during World War II.

He earned a Ph.D. in economics at MIT in 1949 and taught at MIT and at the University of Chicago, where he was dean of the business school. His administration experience included a stint as a senior staff economist with President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Council of Economic Advisers and as Nixon’s OMB director.

Shultz was president of the construction and engineering company Bechtel Group from 1975-1982 and taught part-time at Stanford University before joining the Reagan administration in 1982, replacing Alexander Haig, who resigned after frequent clashes with other members of the administration.

A rare public disagreement between Reagan and Shultz came in 1985 when the president ordered thousands of government employees with access to highly classified information to take a “lie detector” test as a way to plug leaks of information. Shultz told reporters, “The minute in this government that I am not trusted is the day that I leave.” The administration soon backed off the demand.

A year later, Shultz submitted to a government-wide drug test considered far more reliable.

A more serious disagreement was over the secret arms sales to Iran in 1985 in hopes of securing the release of American hostages held in Lebanon by Hezbollah militants. Although Shultz objected, Reagan went ahead with the deal and millions of dollars from Iran went to right-wing Contra guerrillas in Nicaragua. The ensuing Iran-Contra scandal swamped the administration, to Shultz’s dismay.

In 1986 testimony to the House Foreign Affairs Committee, he lamented that “nothing ever gets settled in this town. It’s not like running a company or even a university. It’s a seething debating society in which the debate never stops, in which people never give up, including me, and that’s the atmosphere in which you administer.”

After Reagan left office, Shultz returned to Bechtel, having been the longest serving secretary of state since Cordell Hull under President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

He retired from Bechtel’s board in 2006 and returned to Stanford and the Hoover Institution.

In 2000, he became an early supporter of the presidential candidacy of George W. Bush, whose father had been vice president while Shultz was secretary of state. Schultz served as an informal adviser to the campaign.

Shultz remained an ardent arms control advocate in his later years but retained an iconoclastic streak, speaking out against several mainstream Republican policy positions. He created some controversy by calling the war on recreational drugs, championed by Reagan, a failure and raised eyebrows by decrying the longstanding U.S. embargo on Cuba as “insane.”

He was also a prominent proponent of efforts to fight the effects of climate change, warning that ignoring the risks was suicidal.

A pragmatist, Shultz, along with former GOP Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, made headlines during the 2016 presidential campaign when he declined to endorse Republican nominee Donald Trump after being quoted as saying “God help us” when asked about the possibility of Trump in the White House.

Shultz was married to Helena “Obie” O’Brien, an Army nurse he met in the Pacific in World War II, and they had five children. After her death, in 1995, he married Charlotte Maillard, San Francisco’s protocol chief, in 1997.

Shultz was awarded the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, in 1989.

Survivors include his wife, five children, 11 grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren.

Funeral arrangements were not immediately announced.

Longtime AP Diplomatic Writer Barry Schweid, who died in 2015, contributed to this report.