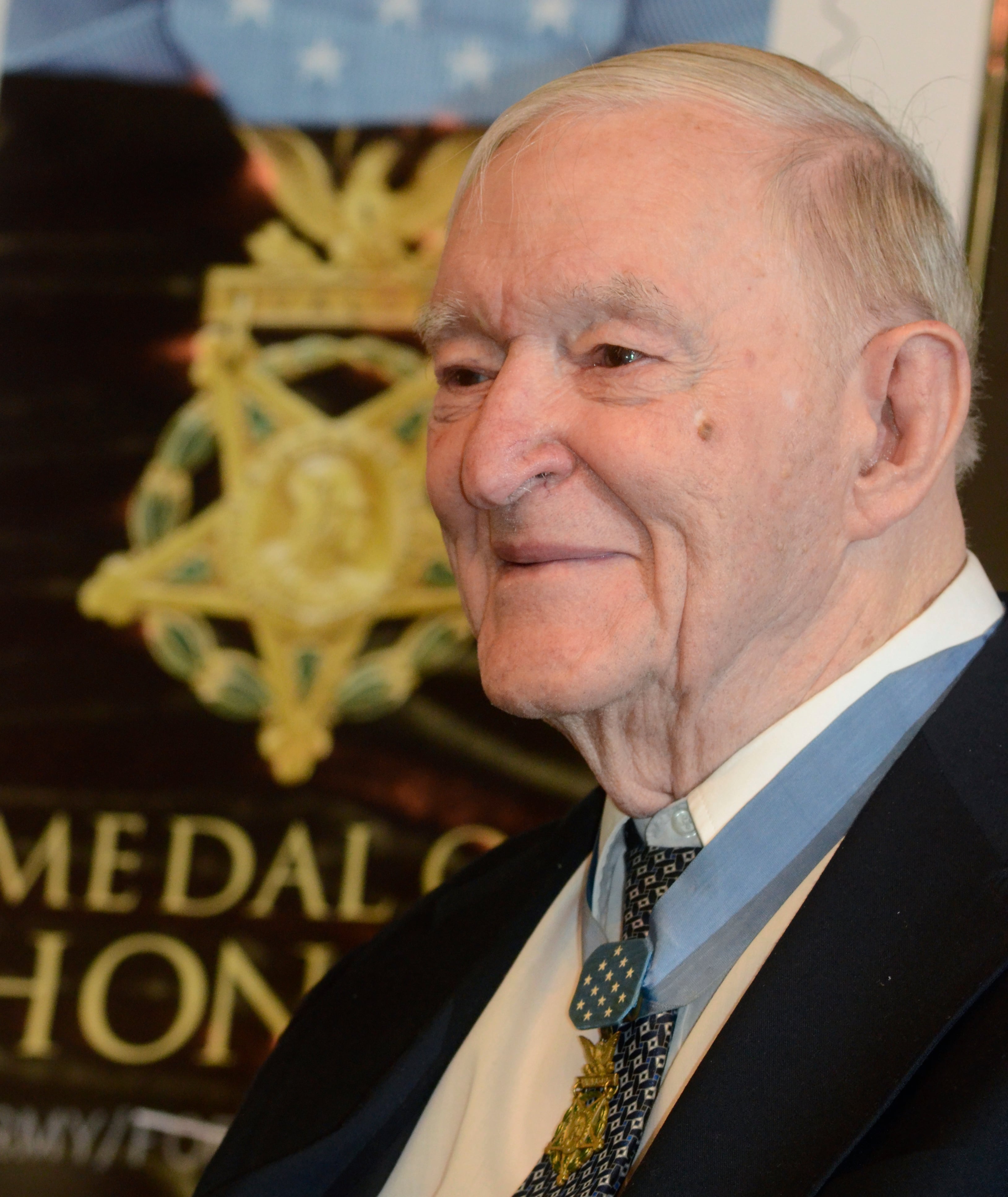

On April 6, the nation’s oldest Medal of Honor recipient, Charles H. Coolidge, died at the age of 99.

The unassuming and quiet Coolidge passed peacefully while surrounded by family at his namesake, the Charles H. Coolidge National Medal of Honor Heritage Center in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

With the death of Coolidge, Hershel “Woody” Williams, 97, who was awarded the nation’s highest decoration for his actions on Iwo Jima, is now the Medal’s oldest surviving recipient.

“We both have been blessed by God with a long, long life,” Williams told The New York Times on Wednesday.

Born on August 4, 1921, Coolidge was drafted into the military in 1942 and assigned to Company M of the 3rd Battalion, 141st Infantry Regiment, 36th Division. Formed in 1917 and composed largely of Texas National Guard troops, the outfit was aptly dubbed the “Texas” division.

Sgt. Coolidge saw action in North Africa and Italy with the 36th before transferring to France in 1944. In the fall of that year, Coolidge found himself in charge of alarmingly green troops — replacements for those killed and wounded from the bloody slog through France. Almost none of the new arrivals had seen combat.

Despite their inexperience, “his unit was nevertheless ordered to hold off the German forces threatening to attack the right flank of the division’s Third Battalion, 141st Infantry, which was massing with two other battalions outside the tiny town of Belmont-sur-Buttant,” according to the Times.

On October 24, 1944, the 23-year-old Coolidge and about 30 soldiers under his command found themselves desperately outnumbered, facing down a swarm of German troops supported by tanks.

Amid rain and dense woods, Coolidge attempted “to bluff the Germans by a show of assurance and boldness called upon them to surrender, whereupon the enemy opened fire,” his citation reads.

The firefight marked the first time many of his men had ever engaged the enemy.

Over the course of four days of continuous fighting, the Americans repeatedly repulsed the numerically superior enemy.

Coolidge recalled in a 2014 interview with the University of Tennessee that on the fifth day, with two German tanks within 25 yards of him, he heard a German tank commander shout in perfect English, “Do you guys wanna give up?”

Standing to face the German, Coolidge calmly replied, “I’m sorry, Mac, you’ve gotta come and get me.”

After that, he said, the Germans took their 88mm turret gun and fired five times right where Coolidge had been standing seconds prior.

“When a shot went one way, I went the other way,” he added.

Dodging behind trees to avoid enemy fire, Coolidge “Secure[ed] all the hand grenades he could carry, [then] he crawled forward and inflicted heavy casualties on the advancing enemy,” according to his citation.

Somehow, the Tennessean emerged unscathed despite the maelstrom of bullets, receiving only a small scratch on the toe of his boot from the battle.

Shortly thereafter, Coolidge, “displaying great coolness and courage, directed and conducted an orderly withdrawal, being himself the last to leave the position.”

The men of the 141st Infantry Regiment were then able to rejoin the Third Battalion, who were positioned a few hundred yards away.

On June 18, 1945, in a rare battlefield ceremony at a bombed out-airfield near Dornstadt, Germany, Coolidge was awarded the Medal of Honor by Lt. Gen. Wade H. Haislip.

After leaving the military in 1945, Coolidge joined his family’s business, Chattanooga Printing & Engraving, where he worked until his retirement in 2017 at the age of 95.

Coolidge frequently spoke of his time in the Army, but despite any adulation, the soft-spoken Tennessean was adamant that, when it came to fighting, “There are a lot of people scared to death, especially if you’re a replacement, never been in combat.

“There’s no glory in the infantry.”

Claire Barrett is the Strategic Operations Editor for Sightline Media and a World War II researcher with an unparalleled affinity for Sir Winston Churchill and Michigan football.