On Nov. 15, 2012, five men sat down for dinner at Ted’s Montana Grill in Crystal City, Virginia. Dressed in shirts and ties, they could’ve easily passed for old friends or business partners, reminiscing on days past. Their friendly conversation gave no hint to the fact that just two decades earlier, three of these men were enemies in the first Gulf War.

It was the first time former Navy pilots Bob Wetzel, 60, and Jeff Zaun, 58, had seen Layth Muneer since the deserts of Iraq in 1991, when their plane was shot down and Muneer, a former major general in the Iraqi Air Force, stopped search parties of Iraqi security forces from killing them.

Now, almost another decade later, Muneer, 74, is still in the U.S. and struggling to be granted asylum, let alone get a green card. Wetzel and Zaun are committed to helping their captor-turned-friend become a citizen.

Jan. 17, 1991

Four U.S. Navy A-6 Intruders flew low over the Iraqi desert as they approached H-3 Airbase. Their mission, to cripple the base’s missile and air defense capabilities with cluster bombs, was a key part of the air war in Operation Desert Storm, which had begun fewer than 24 hours before.

Wetzel and Zaun piloted the second A-6 in the strike force, escorted by a complement of fighter jets and radar-jamming aircraft. They were only minutes from their target when anti-aircraft artillery and parachute flares lit up the clear night sky.

“The AAA was very intense, and I knew from there that we were going to get shot down,” said Wetzel. “I knew we weren’t going to get through this without getting hit by something, because the whole sky was lit up.”

At 10 miles away from H-3 (just over a minute at their speed of 450 knots), Wetzel spotted an incoming surface-to-air missile to their front and outmaneuvered it. About 30 seconds later, another came in from the right. Wetzel looked up from the gauges in his cockpit just in time to see it pulling lead on their jet. Turning hard in the SAM’s direction, he managed to outmaneuver his second SAM of the night.

He wouldn’t be so lucky with the third.

As Wetzel watched the evaded missile fly off into the night and continued his turn away from it, an explosion rocked the plane. A third SAM he hadn’t seen coming had struck the right-side engine. The plane shook violently, and warning lights brightened the cockpit.

“The only thing I remember really clearly was a fire that I could see in the windscreen, and I could hear the engine eating itself,” said Zaun. Seconds after the plane’s first engine went out, the second ground to a halt.

Unable to fly further, Zaun and Wetzel both remember calling for ejection. Next thing they knew, the pilots were on the desert floor in clear sight of the enemy airfield. The ejector blast had knocked them unconscious for the descent and left Wetzel with multiple broken bones.

A dazed and disoriented Zaun rose to his feet but was unable to locate his weapon or radio. In his delirium, he recalls repeatedly searched his parachute for the missing items. Wetzel had landed nearby and was in poor condition, but they were too close to the airfield to be safe. They needed to get moving.

Zaun helped Wetzel remove his parachute harness, and the two began walking and crawling up steep sand dunes in the direction of the Jordanian border to their southwest. The duo only made it about a half-mile into their trek when they turned around and saw trucks investigating the site where they’d stowed their parachutes. Search parties from the airbase were on their tracks; it was only a matter of time now before they were captured.

The pilots hid in a gulley, but as an Iraqi truck approached their position, it was clear the enemy couldn’t see them hiding and might run them over. Zaun stepped out in front of the truck with his arms raised, and the downed pilots made their surrender.

Small arms fire filled the air — the Iraqis’ signal that they had found the men. More troops began to gather around, and soon an angry mob had formed, kicking and grabbing at the two pilots.

Then a new group showed up on the scene — an Iraqi Air Force officer and his airmen — and brought order to the crowd.

“He was with some of his troops and he formed like a little perimeter around us with his guys — I want to say maybe eight or 10 guys — who were protecting us from this angry mob and got us over to his jeep,” said Wetzel.

The officer saw to it that the two pilots were safely delivered onto H-3 and to the infirmary, where they were given medical care until the following morning, when they were taken to Baghdad.

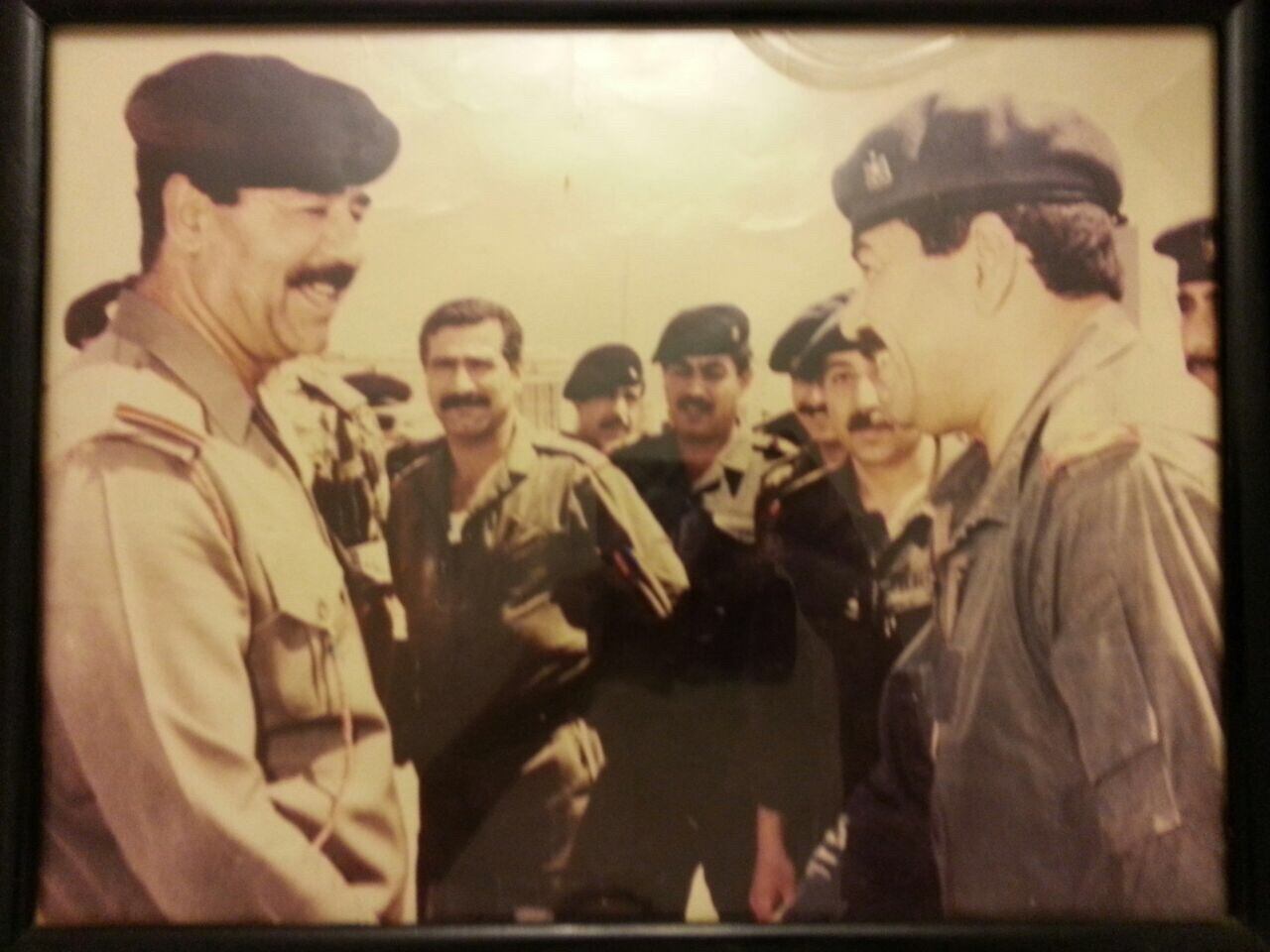

H-3 Airbase

General Layth Muneer was a seasoned veteran of the Iraqi Air Force. As a fighter pilot, he had spent the early years of his career training in Pakistan and Iraq on both American and Russian-made platforms including T-37s, F-86s, and MiG 21s and 23s. He also served on flight missions for allied countries like India and Egypt. In 1991, he was serving as commander of H-3, an Iraqi air force base about 300 miles west of Baghdad in Al-Anbar Governate.

When the attacking A-6 Intruders made their approach on Jan. 17, Muneer’s radar officer didn’t spot the aircraft until they were about four minutes out.

“I said, ‘Oh my God.’ Then I gave the order for all the weapons and missiles to be alert and on fire,” Muneer told Military Times.

Minutes later, the bombing began. From the officer’s mess to administrative offices, hangars to soldiers’ quarters, Muneer said coalition planes bombed nearly everything. The general and his airmen hid from the strikes in underground shelters, emerging only after the aircraft had passed.

Throughout the attack, Muneer’s airmen had been firing AAA and SAMs, including both Russian radar-guided missiles and the heat-seeking French Rolands that took down Wetzel and Zaun. H-3 had been mercilessly punished by coalition cluster bombs and missiles, but Muneer’s airmen kept fighting, and they kept thinking they had shot down enemy aircraft.

“Every day, every hour, my security force would bring me pieces of bombs and drop tanks and frame them as an aircraft they had shot down,” said Muneer. “Finally, they brought me a nosewheel and I said, ‘Oh, look at this. This is an aircraft. Now you are right… it is an American airplane.’”

H-3′s air defense also managed to hit another A-6 in the strike on Jan. 17. Although the plane was damaged, its crew was able to continue flying to safety over Saudi Arabia.

The nosewheel his security forces had recovered was still hot, so Muneer gathered a search party to locate the downed aircraft and its pilots. He instructed the searchers to fire a weapon into the air when they’d found something.

The first searchers to locate the downed pilots, however, weren’t Muneer’s airmen; they were the military commandos who guarded H-3 from the outside.

“[Wetzel and Zaun] were scared by those people,” said Muneer. “As the commander of the base, I gave my order: ‘Stop shooting, and don’t harm the pilots. They are prisoners of war; we should go according to the Geneva Convention.’”

“But they still wanted to kill them. They hit them, they stole their things before I arrived,” said Muneer. Muneer safely escorted the prisoners to his jeep and then left them at the base infirmary under the watch of guards he personally trusted.

At the time, Saddam Hussein’s government offered rewards to citizens who brought in enemy combatants, dead or alive. But military personnel were not eligible for such rewards, so some of the Iraqi soldiers and airmen wanted to hand over the pilots to locals and divvy up the prize, according to Muneer. Despite pressure from other officials on the base, including a cousin of Saddam Hussein, Muneer would not let them take the prisoners.

The next day, the general sent the two POWs to Baghdad with his personal driver.

Preparing for Desert Storm

Back on the aircraft carrier Saratoga, anchored some 500 miles from H-3 in the Red Sea, Zaun and Wetzel’s chain of command had no idea whether they were dead or alive.

The carrier had steamed out of port in August 1990 for a six-month cruise in the Mediterranean. Just a week before the ship was set to leave, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait.

Instead of the Mediterranean port calls the sailors on board the Saratoga had been expecting, the cruise became a trip to the Red Sea, where pilots like Zaun and Wetzel would spend their days training and planning for war with Iraq.

“The idea that we were maybe going on a war cruise made saying goodbye a little more emotional this time,” said Wetzel, who had to bid farewell to his fiancé. But he was hopeful that it would all work out according to schedule. The cruise left in August, and the wedding date was set for March 2 — more than six months away.

Both Zaun and Wetzel were on their second cruises and relatively experienced as pilots when the war began. In fact, when the duo was shot down over H-3, Zaun was only three hours away from having flown 1,000 hours in an A-6 cockpit.

Given his experience, Zaun served as lead planner for the strike on H-3. “I planned the dickens out of it… I really knew that airfield well because I’d studied it for months,” he said.

The first plane through would hit the airfield’s control tower. Wetzel and Zaun would follow and destroy the fuel farm, and the final two planes would target the base’s hangars where fighter jets were located. The attack aircraft would fly low over the desert to avoid radar and make it difficult for high-flying enemy fighter jets to shoot down at them.

The twinjet, all-weather-attack A-6 Intruder was the perfect plane for the job. Grumman designed the aircraft to be capable of flying low, even at night, and the side-by-side seats in the cockpit made the bombardier/navigator’s job significantly easier.

Zaun would serve as the duo’s B/N on Jan. 17, monitoring the plane’s large radar display and targeting computers to ensure their bombs would land on target. They would be dropping Mark 20 Rockeye II cluster bombs, which carry 247 individual bomblets to spread destruction over a wide area.

“The A-6 was the workhorse for attack, especially at night. We could carry way more and we weren’t any more vulnerable,” said Zaun.

When Wetzel was still in training, he knew the A-6 was the plane he wanted to pilot.

“The A-6 was my first choice instead of a fighter plane. I liked to fly at the low levels,” said Wetzel.

For both men, the beginning of the Gulf War was the result of years of preparation.

Zaun and Wetzel both grew up in New Jersey. Zaun graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1984 with the goal of flying attack planes. Wetzel, who entered Aviation Officer Candidate School in 1985, was in his senior year of college when he ran into a Navy recruiter who showed him videos of the Blue Angels and convinced him he could become a pilot. “I always thought of flying airplanes, but I didn’t know anybody that was a pilot. I didn’t even know many people in the military,” said Wetzel.

Captivity

The bumpy ride from H-3 to Baghdad would be the last time the two pilots saw each other for more than a month.

Zaun was sent to the Iraqi secret police, where he was beaten, often with rubber mallets or hoses to the shins. He recalls rarely being punched with a closed fist; however, slaps were regular. His interrogators eventually said that they would kill him unless he went on TV and answered interview questions as he was instructed to.

“They told me all the questions they were going to ask along with all the answers I was supposed to give,” said Zaun. “… I just tried to sound as insincere as possible. I was pretty sure Americans wouldn’t buy it.”

The interview was the first time Zaun’s family and shipmates learned he was still alive.

Shortly after being brought to the TV station, Zaun was transferred to the custody of the Republican Guard, where the beatings and harassment lessened but food and living quarters were still poor. Despite being malnourished, he focused on doing pushups and maintaining his fitness to pass the time.

The majority of Zaun’s stay was at Biltmore Prison, home of the secret police headquarters. He describes the prison as a dungeon, with dark lighting and cold cells. Prisoners of war were regularly dragged out for interrogations and beatings.

When Wetzel arrived in Baghdad, he was immediately brought to a hospital and treated for a broken left ulna, broken right humerus, compression fracture of his vertebrae, broken right collarbone, and a broken finger. After six days of hospital recovery, he, too, was put in Biltmore to be interrogated.

Wetzel recalls being treated more gently because of his injuries, but secret police interrogators still whipped him and burnt his skin with cigarettes, he said. He would drag on his answers to every question, repeating statements and adding excessive lies and stories to avoid giving away information or being beaten again.

The long, dark days in a prison cell brought on depression for Wetzel, and starting off with serious injuries only made his time in captivity more difficult. He says he prayed and daydreamed every chance he could, often thinking of his hometown in New Jersey or of his fiancé Jackie, waiting for him stateside.

Wetzel never appeared on a TV interview, and until the two pilots were released, his family didn’t know whether he was dead or alive. Zaun and Wetzel saw each other only once in passing during their stay at Biltmore, and it wasn’t until their release that they would speak again.

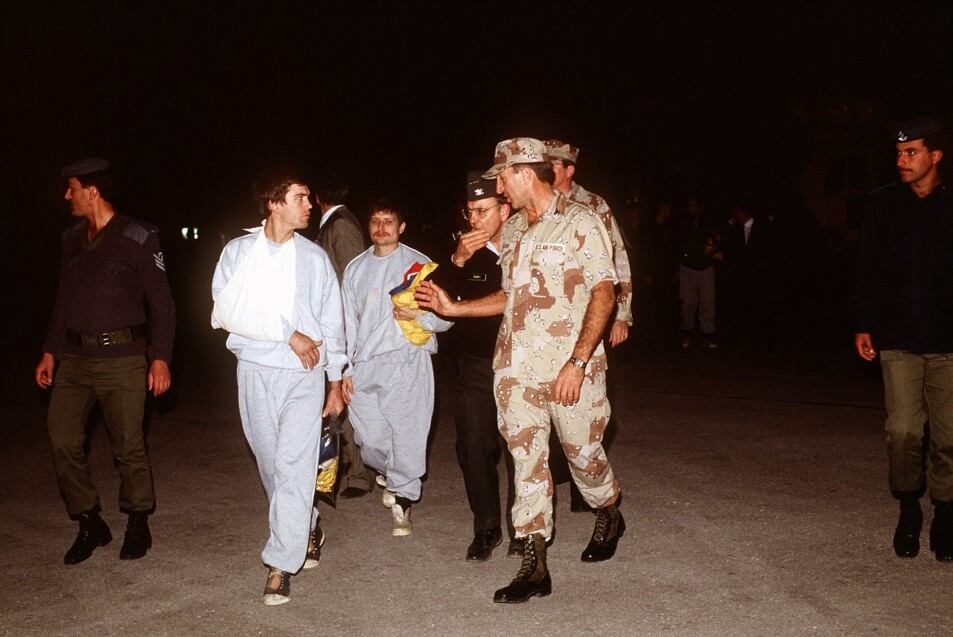

On Feb. 24, the same day the ground war to push Iraq out of Kuwait began, Air Force pilots bombed the secret police headquarters at Biltmore. As a result, Zaun and Wetzel were transferred to Abu Ghraib and then to another prison in Baghdad, spending no more than a few days at each before their release.

On March 2, the same day Wetzel was supposed to be married, the prisoners learned that the war was coming to an end and they would be sent home soon. Two days later, they were released to the Red Cross.

The two spent a total of 46 days in captivity.

In the air, on Wall Street, and on the run

Wetzel and his fiancé were married on June 1, 1991, with many members of his squadron in attendance. This June marks their 30th anniversary.

After receiving medical treatment and evaluations to correct the screws that were put in his arm at the hospital in Baghdad, Wetzel continued to serve as a flight instructor until the Navy began to phase the A-6 out of service. Upon separating from the Navy in September 1995 at the rank of lieutenant, he became a pilot for United Airlines, where he worked for 25 years before retiring to Colorado last fall.

Zaun left the Navy in 1998 at the rank of lieutenant commander and went on to earn his master’s in business administration at the Wharton School of Business. Twice more in his career, he would be present as catastrophe struck. On Sept. 11, 2001, Zaun was working on Wall Street just a few blocks from the World Trade Center when the planes struck.

Then, in 2008, he was working as a credit analyst in a rating agency when the financial crisis hit. Zaun still lives in New Jersey and is in the early stages of writing a book on his experiences.

Muneer continued to serve as the commander of H-3 Airbase and in the Iraqi Air Force for years after Desert Storm, leaving the military in 2003 when the invasion of Iraq began.

He had served his country for 36 years, including as a pilot in the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s. When Saddam Hussein was overthrown and Iraq’s infrastructure began to collapse, Iranian assassins poured over the border to exact their revenge on Iraqi pilots for their part in the conflict. Hundreds of pilots who flew in the Iran-Iraq War were killed, and hundreds more fled.

Muneer first fled to Syria because the country had no laws against Iraqi citizens immigrating, but when he refused to help former Iraqi government officials in hiding plan to take back their government from coalition forces, he was pushed out of Syria as well, according to his son.

Muneer finally moved to Egypt, where his son says he had previously been one of a just a handful of allied pilots to serve under the command of then-Air Force Commander Hosni Mubarak during the Yom Kippur War.

By the time Muneer was on the run, Mubarak was Egypt’s president, and he welcomed his old friend into the country. Muneer enjoyed a comfortable life teaching classes at the Egyptian air academy and talking about the Yom Kippur War on TV.

But in 2011, Mubarak was overthrown and the Muslim Brotherhood was elected into power over Egypt. The new government would not renew Muneer’s residency papers, which were signed off on by Mubarak’s administration, unless he agreed to use his status to spread propaganda in support of the new president. Muneer refused to do so and was forced to flee yet another country.

The former Iraqi general arrived in the U.S. in 2012 to visit his son, Zea Muneer, a sergeant first class in the U.S. Army and Bronze Star recipient. Zea, 43, had immigrated to the U.S. in 2003 and spent more than six years on deployment in Iraq. He is currently a cryptologic analyst in the Army Reserve with more than 15 years of service.

Rather than return to Egypt from his visit, the elder Muneer applied for asylum in the U.S. in 2012. He still hasn’t received it.

Muneer’s case was rejected by immigration services and then reinstated when Zea employed the help of his congressional representative. The case was then transferred to the immigration courts, where the former general’s hearing has been postponed repeatedly. His current hearing date is scheduled for 2024.

Until he receives asylum, Muneer cannot apply for a green card, which would allow him to travel and visit the rest of his children, who are spread out around the world. In the meantime, he has started a business teaching chess and tennis to children in elementary schools in the DC area.

He’s also taken up work as a military advisor, speaking three to four times a year to military intelligence units preparing to engage with foreign countries.

“I don’t know why they don’t approve it. He’s stuck,” said Zea. “Is it something personally? Is there an order saying, ‘General Muneer cannot get asylum?’ I don’t know. He’s just stuck in the immigration system like many people are.”

Reunion

In the months following his arrival in the U.S., Muneer worked hard to locate the two POWs he had saved in the desert decades ago. Despite the best efforts of his son and his attorney, they were unable to do so.

Finally, Muneer told the story to his tennis partner, Rodrigo Cruze. Cruze searched the internet and found contact information for Zaun’s mother.

“My mom called me and told me some Iraqi general wanted to talk to me,” said Zaun. He got in contact with Muneer and set up a time and place for the meeting. Then he called Wetzel.

The two pilots met with Cruze and Layth and Zea Muneer in Crystal City on Nov. 15, 2012. They’ve reconvened almost every year since on Jan. 17 to reminisce and retell their stories of Desert Storm.

“I think about it and I still get the chills. It’s amazing that we ever met up with him again,” said Wetzel. “… I knew who he was on the ground there, but I never saw him again, and in my talks I always talked about this guy who captured us and really saved us from this angry mob.”

It’s hard to imagine that the now 74-year-old man teaching chess at elementary schools and working as a tennis coach is the same man who commanded H-3 Airbase through Desert Storm. For Wetzel and Zaun, it’s even harder to imagine that their friend is unable to gain citizenship after everything he’s done.

“Jeff and I were going to go in January to his trial date and be there alongside him as a character reference, and it got postponed for several years,” said Wetzel. “Hopefully, when the time comes, he’ll be able to get his citizenship. I know there’s a lot of people behind us willing to support him.”

To Zaun, the case for Muneer’s citizenship is clear. “At this point, he is not only someone who acted professionally and probably saved the lives of two Americans, but he has also become a solid American himself,” he said.

Harm Venhuizen is an editorial intern at Military Times. He is studying political science and philosophy at Calvin University, where he's also in the Army ROTC program.