When it’s time to make a decision about sending a ground unit to Europe or an aviation squadron to the Indo-Pacific, it can take the Pentagon weeks to gather information from hundreds of databases to see how those movements will affect long-term readiness.

That might not be the case for much longer.

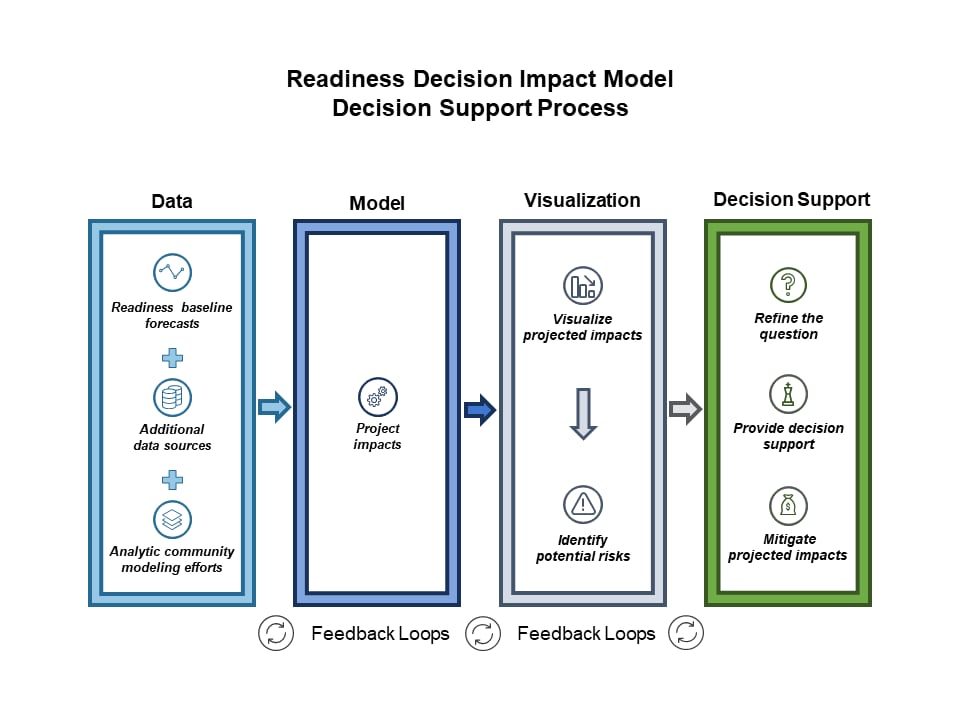

The Readiness Decision Impact Model, in development at the Defense Department’s readiness office, can take a question such as, “How will extending a squadron’s deployment now affect its maintenance in two years?” and in minutes pull from multiple databases to create an impact estimate that can be used to inform senior leader decisions.

“A lot of decision making is currently based on siloed information, and it’s limited in terms of how we can project what those impacts are,” Kimberly Jackson, DoD’s deputy assistant secretary for force readiness, told Military Times in a Dec. 19 interview. “So, it goes from being something pretty well informed and discrete in the near term, to it getting harder to predict.”

Generally, readiness impacts can be predicted in the current budget year, but beyond that, there hasn’t been an algorithm that can calculate all of the cascading effects of an operational decision.

“We have data siloed all over the department. We have so much data, it’s not even appropriate to call it a data lake — it’s an absolute data ocean,” Jackson said. “But how do you make it connect? And how do you design the model so that you can actually make sense of it? Because data — if it’s not utilized in a model, if it’s not applied, does it actually mean anything?”

The tool originated in the Marine Corps, as the service was putting together its Force Design 2030 concept, an overhaul of equipment and personnel needs with an eye toward the next fight. With support from Deputy Defense Secretary Kathleen Hicks, the Pentagon is looking to use it department-wide.

Something like the RDIM might have come in handy, for instance, during the process to modernize the Marine Corps’ infantry battalion design.

When issues came up with the original plan, the service put together an integrated product team to suggest changes. The RDIM, meanwhile, could have modeled the effects of the original plan and avoided the need for mid-effort changes.

RELATED

Redefining readiness

Marine Corps Commandant Gen. David Berger, along with Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. CQ Brown, wrote about the need for a new definition of readiness in a piece for War on the Rocks in 2021.

“Our argument is simple: The joint force requires a holistic, rigorous, and analytical framework to assess readiness properly,” they wrote. “Over past decades, readiness has become synonymous with ‘availability’; — largely a measure of military units available for immediate deployment and ready to ‘fight tonight’ — while ‘capability’ took on a lesser role in the calculation.

“Perhaps appropriate for an earlier era, this framework for readiness is poorly suited to an environment characterized by great-power competition. It largely ignores the capabilities of these ‘ready’ forces and begs the question, ready for what?”

The RDIM hopes to answer that question. While a unit may be in garrison and technically available to deploy, an impact model might show that they are slightly behind on maintenance and training from a previous deployment, and that another rotation would yield a bigger gap to close once redeployed.

“And this is part of a broader conversation about how should we be thinking about and measuring readiness writ large; just because a unit has completed its training program of instruction ... doesn’t necessarily mean that they are fit to accomplish the mission,” Jackson said. “And it could be vice versa as well. They could have lower readiness ratings, but they’re actually very, very able and capable to accomplish the mission.”

With that in mind, Jackson added, there are plans to use RDIM to look at specific types of readiness, including at the personnel level.

“So, as an example, one thing that we’re very interested in is, what’s the relationship between unit readiness, sexual harassment, sexual assault and unit cohesion?” she said. “And what’s the relationship between unit cohesion and readiness? Because you know that if a unit goes out to conduct its mission, and you have a high level of cohesion, we all know in our gut that they’re likely going to be able to accomplish their mission in a more effective or more efficient manner than a unit that isn’t cohesive, but we don’t have the data that backs that up.”

Training is perhaps the biggest challenge to quantify, because there is so much variation in the quality of training. Still, it is one category Jackson hopes RDIM can eventually tackle.

For now, the plan is to have a solid aviation maintenance model ready and able to create assessments for senior leaders in the spring. Eventually, Jackson hopes an RDIM assessment will be a regular part of all DoD decision making.

“I think not only is that our vision, but I believe that that’s reflective of the support that we have gotten from the deputy [defense secretary],” she said. “Additionally, every senior-level conversation I’m in, somebody is asking for [a tool like] the RDIM, even if they’re not calling it the RDIM.”

Which is not to say that a computer model will be the deciding factor. It can, however, help personnel make better decisions.

Many times, politics or ethics are priorities when deciding whether to deploy troops, but the RDIM can give senior leaders a heads-up on what other actions might be needed to prevent readiness gaps in the long term.

“The RDIM might not change a decision, but it will give a better understanding of mitigation actions and potential trade-offs,” Jackson said.

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.