Editor’s note: This article first appeared on The War Horse, an award-winning nonprofit news organization educating the public on military service. Subscribe to their newsletter.

The profanity-laced email that landed in thousands of Coast Guard inboxes this past May wasn’t intended to foment a rebellion in the nation’s most under-the-radar branch of the military. It wasn’t meant to get cited in a congressional hearing. It was just sheer, scorching frustration.

The 4,000-word screed from an anonymous, encrypted email account focused on alleged sexual misconduct at Sector Mobile in Alabama and claims the Coast Guard mishandled the investigation. Not long after firing off the email, the sender, who called themself Whistler McGee, also posted the letter on Facebook.

“I was just going to make the Facebook account, post it, and then bail,” McGee told The War Horse in an interview last month. “But within two, three hours, it just exploded.”

McGee started receiving hundreds of emails from Coast Guard members with similar experiences. Soon, current and former service members were publicly posting stories of alleged sexual assaults, many of them under the hashtag #ImWithWhistler, sharing how they also felt the Coast Guard had failed them. Leaked documents — including internal guidance on how commands should respond to the social media activity — soon followed.

Now, two months after Whistler McGee’s initial email, what started as a quest for vengeance has erupted into a rank-and-file reckoning over how the military handles sexual assaults and who should drive the conversation about whether leadership is doing enough to address the problem.

“In my view, this is the worst sexual assault scandal we have ever seen” in the military, said Lindsey Knapp, a former Army victim advocate who now works with sexual assault survivors across all military branches.

“It’s just so pervasive. And then once one person felt safe enough to whistleblow, they all just kind of — we finally hit the tipping point.”

To report this story, The War Horse reviewed nearly a hundred social media posts and interviewed multiple people connected to anonymous pages. We granted anonymity to McGee and others so they could speak freely on the phenomenon, but are not quoting them about specific allegations.

The Coast Guard has been under increasing public and congressional scrutiny over the past year after CNN revealed that Coast Guard officials investigated the handling of sexual assault cases at the Coast Guard Academy, and then declined to make public the final report. The investigation, called Operation Fouled Anchor, showed that many perpetrators of sexual assault at the academy in the 1980s and 1990s were not punished and continued to advance in the Coast Guard.

But the explosion of outrage on social media has moved the conversation beyond the academy and toward a relentless push to force Coast Guard leaders to hold perpetrators accountable and confront what advocates say is an epidemic of sexual assault and toxic leadership in the ranks.

“Leadership needs to realize that anything they put out is going to pop up” online, one junior officer told The War Horse. “When it comes down to it, it’s information warfare.”

More bombshells fuel scandal

With Congress already scolding Coast Guard leadership over its handling of sexual assault allegations, another scandal arose in November when CNN revealed the Coast Guard had declined to release a second study, this one detailing a culture of racism, sexism, and toxic leadership in the service.

Then, last month, another bombshell: The Coast Guard Academy’s longtime sexual assault response coordinator, Shannon Norenberg, resigned from her position, issuing a public statement saying that she had been used to lie to sexual assault survivors and discourage them from speaking to Congress. (On Wednesday evening, Norenberg issued another statement reversing course and pledging to stay in her role until Coast Guard leaders “repair the damage done to victims of Operation Fouled Anchor.”)

For the most part, public attention has focused on misconduct in the officer corps, with senior leadership repeatedly vowing, internally and publicly, to stop sexual assault. But advocates are quick to point out that the problem doesn’t end with officers.

“This is an issue that is pervasive, that impacts every rank, every paygrade,” says Kimberly McLear, a retired Coast Guard officer who has been advocating for the service to address internal sexism and racism since becoming a whistleblower in 2014. “It’s not only happening at the Coast Guard Academy.”

Problems of sexual assault are endemic across all military branches, says Don Christensen, a retired Air Force colonel who served as chief prosecutor of the Air Force. Distrust among the rank-and-file over leaders’ ability to address sexual assault and toxic leadership is common.

But sexual assault survivors have long struggled to force change through official military channels.

“Ever since we had Tailhook and Paula Coughlin coming forward in 1991, that’s how it goes,” says Stephanie Bonnes, a sociologist at the University of New Haven who studies sexual misconduct in the military. “You report; nothing’s done. You try the chain of command. You try the military system. It doesn’t get anywhere.”

So victims turn to other avenues, like the media or the civil courts, to try to push for change from the outside, Bonnes says. But in recent years, this frustration has increasingly played out on social media.

In 2017, after The War Horse broke the Marines United scandal, which exposed hundreds of male Marines posting nude photos of servicewomen in a closed Facebook group, female Marines took to social media to express their anger. In 2020, after Spc. Vanessa Guillén disappeared at Fort Hood and was later found murdered by a fellow soldier, military women posted about their experiences under the hashtag #IAmVanessaGuillen. Both scandals ultimately changed military law.

“This is the Coast Guard’s moment,” Bonnes said.

Why the Coast Guard is different

The Coast Guard’s #MeToo movement is unique in that survivors are sharing their experiences in graphic detail, sometimes directly naming the alleged perpetrators. The chorus of voices online also increasingly includes bystander accounts, where people who have not been directly involved are reporting cultural problems they say they’ve witnessed.

“It’s not just personal stories,” Bonnes says. “It’s stories of other people watching harassment unfold and talking about it. And that is really powerful.”

The unique nature of the Coast Guard also likely helped the movement gain traction, experts said. The service is small — at about 50,000 people, it’s smaller than the NYPD — and service members are often stationed in tight-knit units where they directly know many of their shipmates, meaning news travels fast.

“I think it’s culturally different than the rest of the services,” Christensen said. “There’s more of a feeling that this is something they [survivors] can do and have their voice heard.”

The explosion of frustration is set against the backdrop of congressional hearings in which lawmakers have publicly accused Coast Guard leaders of covering up misconduct. But while the Operation Fouled Anchor scandal has focused on the officer corps, the growing movement online stems largely from the junior ranks of the Coast Guard, many of them savvy social media operators, who say they are tired of empty promises they’ve heard before.

“The movement that you see, I think, has been in effect for a while,” says the administrator behind the Pettiest Officer in the Coast Guard, a Facebook meme account that has become a central repository for accounts of sexual assault. “Now it’s organized.”

The alleged misconduct spans decades, but the posts paint a picture of ongoing disarray, with certain patterns surfacing again and again.

“My recruiter told me if I didn’t do things for him, I would never be allowed in the Coast Guard,” one post reads. “So I traded sex for my dream of being in the Coast Guard because I was 18-19 and didn’t know any better.”

Other accounts accuse higher-ranking members of withholding things like training or qualifications needed for advancement in exchange for sex or as punishment for reporting misconduct. Women and men described being forced to work alongside their alleged abusers on ships or isolated units.

Many of the posters say they reported the behavior to their chain of command, but it wasn’t taken seriously or that perpetrators were not held accountable. Some say their attackers were allowed to “quietly retire” with benefits, while others posted that their abusers continued to serve in the Coast Guard.

“My direct command wanted him kicked out,” one poster wrote of her alleged assailant, but higher-ups dropped the charges.

“[They] claimed he was probably just lonely.”

‘Write my own narrative’

This spring, the Coast Guard asked several survivors of sexual assault to tell their stories in videos it planned to release during Sexual Assault Prevention Month in April. But in mid-April, worried that the service was dragging its feet, Meghan Klement, one of the participants, published her video on her own.

“I just had decided myself, because I’m not in the Coast Guard anymore, that I can write my own narrative now,” said Klement, who served in the Coast Guard from 2012 to 2015 and currently works as a photographer in Oregon. “We really wanted people to see it.”

About a month later, Whistler McGee posted their letter. Around the same time, an internal Coast Guard memo appeared online referring to the delay in releasing the videos.

“[The Office of Public Affairs] has concerns related to the use and distribution of the videos,” the memo read. “This could continue to exacerbate the narrative being advanced by some that the Coast Guard is in a sexual assault crisis now. …”

Shortly after the internal memo appeared, the service published all the survivor videos.

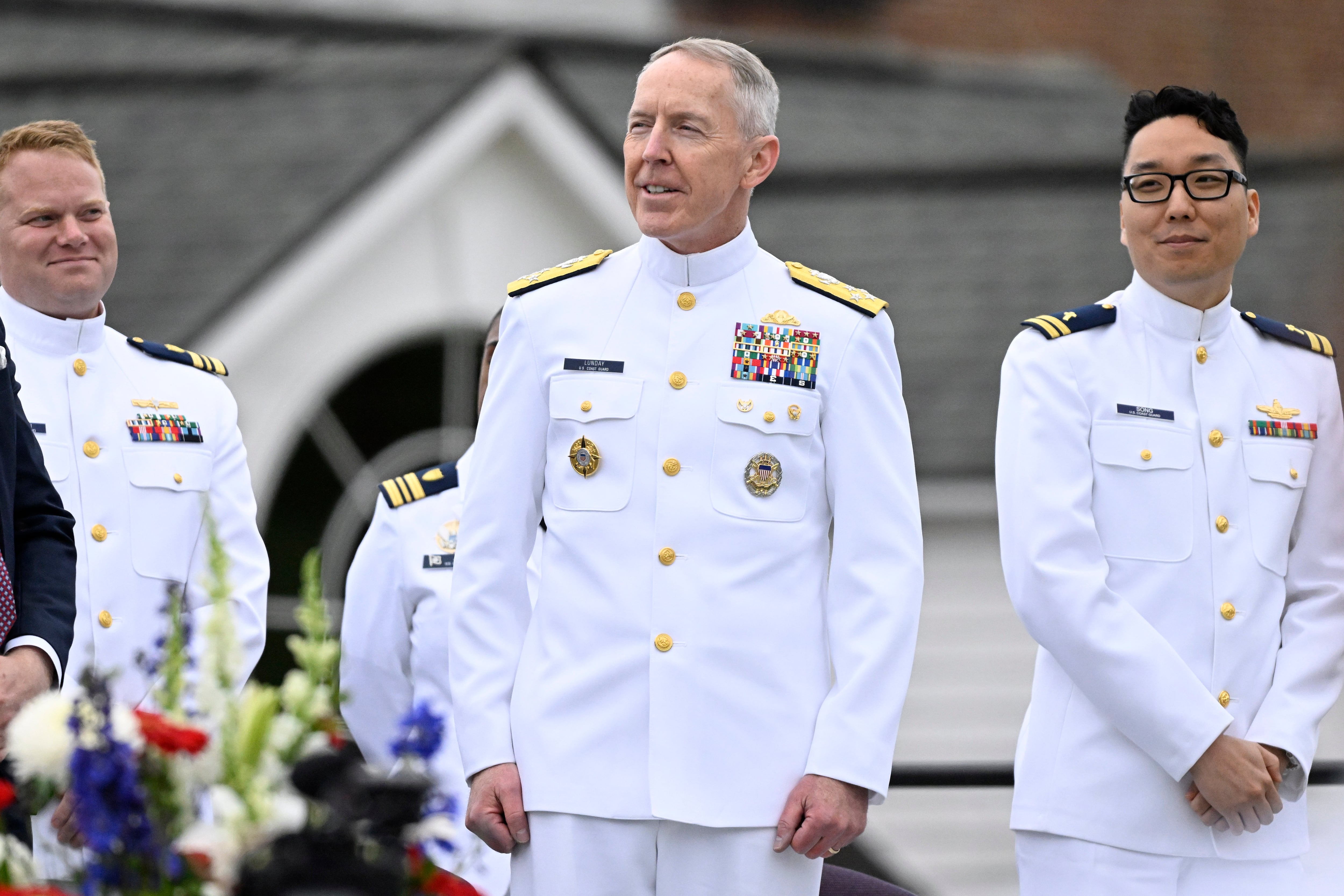

At a congressional hearing in mid-June, lawmakers raised Whistler McGee’s letter as an indicator of culture problems in the service, and asked Adm. Linda Fagan, the commandant of the Coast Guard, about the videos and the memo, arguing that it showed an unwillingness to confront sexual misconduct allegations. Sen. Richard Blumenthal said that the committee had received reports from nearly 40 whistleblowers over the past several months attesting to an ongoing problem with sexual assault in the service.

“I want to stop creating victims,” Fagan said. “But for the victims that we do have in the organization, I am 100% committed to fully supporting them and their needs.” She told lawmakers that the allegations in Whistler McGee’s email were fully investigated, and the inquiry was still open.

In a statement to The War Horse, the Coast Guard said that it was aware of recent social media posts regarding sexual assault.

“The Coast Guard has and will continue to investigate reports of sexual assault involving Coast Guard members when we become aware of information that is sufficient to initiate an investigation,” the statement said.

However, the Coast Guard added that it cannot guarantee that it will see or be able to act on all social media posts or other informal reports, and encouraged survivors to report incidents to sexual assault response coordinators, victim advocates, or the Coast Guard Investigative Service.

How will this end?

Where this all leads — for the Coast Guard and every branch of the military — is an open question. Officers and enlisted members who spoke with The War Horse said they were confident momentum would continue to build.

“So many of us have been able to connect with each other,” Klement said. “I think, with all of the survivors being so vocal, that it’s continued to put pressure for accountability onto the Coast Guard.”

Online accounts of sexual assaults, spanning from the 1980s to just weeks ago, have now come from active-duty members, veterans, junior enlisted members, and high-ranking officers. People are crossing traditional military boundaries to compare notes on their experiences, speak with lawmakers and Department of Homeland Security investigators, and connect with outside nonprofits and organizations, some of which are new to the conversation around military culture and sexual assault.

“Anytime stories are being collected in a somewhat organized way, it can be very effective,” Bonnes says, and it’s likely the Coast Guard will have to respond in some way. “But the effect of what they do really depends on advocacy, activism, and how organized the messaging about what needs to be done to address these things is.”

In early June, McLear’s longtime advocacy organization, Right the Ship, published an open letter arguing that the wave of shared stories was evidence of a “woeful disregard for justice, accountability, safety, and dignity,” and called for holding perpetrators and senior leaders accountable, pointing to the Feres doctrine — the legal principle that prevents service members harmed in the course of their service from suing the military — as a prime obstacle to accountability.

The letter was cosigned by 12 civilian organizations that deal with issues from military sexual assault and government accountability to workplace bullying and countering nondisclosure agreements. Since the letter was published, McLear said, three additional organizations have partnered with her group.

“The coalition-building at its heart is really about reminding all of us that we all have a duty to hold the Coast Guard accountable,” she said. “If we’re going to tackle the roots of a culture that is systemic, that means we need to have a diverse coalition that spans all of the ways that these systemic issues are showing up, from rape to racism to hazing to bullying.”

This War Horse investigation was reported by Sonner Kehrt, edited by Mike Frankel, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Abbie Bennett wrote the headlines.