When a soldier takes an enemy round to his or her body armor and lives to fight another day, it’s a good-news story for the engineers who develop that protection.

But as the Army develops lighter armor plates that offer greater levels of comfort and maneuver, there’s a secondary concern: blunt trauma damage from the armor’s response to a bullet that leaves soldiers with broken ribs or internal injuries.

Known as Behind Armor Blunt Trauma, or BABT, this aftereffect became a specific research focus for the Army in 2021 and has spawned inventions and protocols that may inform trauma study and protective designs beyond the military, including vehicle crash tests, athletic protective gear and more.

That’s according to Joe McEntire, a senior scientist and research medical engineer with the Army Aeromedical Research Laboratory.

McEntire, who has worked at the lab for more than three decades, said the science of BABT has to do with energy transfer. While the Army’s current modular scalable vest, with its hard ballistic plates, is substantially lighter than its predecessors, the services are always seeking out ways to cut weight.

And with lighter materials, McEntire said, there is greater risk that armor will deform inward when it absorbs a blow, potentially leading to serious thoracic cavity damage.

While this effect has been generally understood for some time, engineers have long relied on 50-year-old experiments involving goats shot with nonlethal rounds while wearing body armor, and tests with clay blocks positioned behind protective plates, he said.

The result, an industry standard that allowed 44 millimeters’ worth of armor deformation, was based on a limited test sample and hardly precise, McEntire said.

“Clay is supposed to be a plastic material where it reforms and doesn’t rebound,” he said. “Well, unfortunately, it actually does have a source of energy and [does rebound]. So, when you measure the depth of penetration or deformation, there’s some error associated with it.”

To gather more reliable data, the Army has signed $8 million in contracts with the Medical College of Wisconsin, which in turn subcontracted with the University of Virginia and Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan.

Their objective is to develop better and more reliable “injury criteria,” as they’re technically called, to govern the safe design of the next generation of body armor.

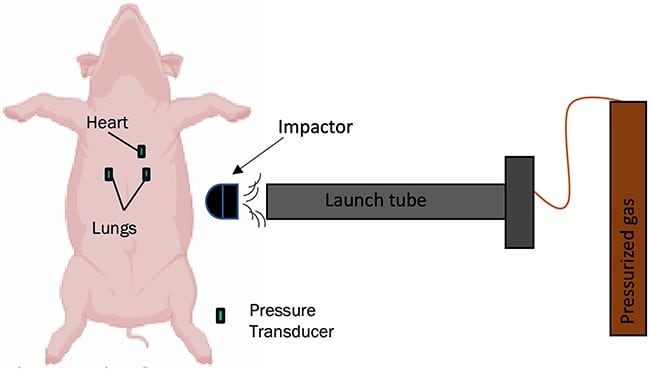

In August, the academic journal Military Medicine published the latest research in the BABT initiative: an experiment involving seven anesthetized pigs subjected to blows at different speeds and force levels from a custom-designed device — like a free-flying half-softball made from hard polymer with a built-in accelerometer — called an “indenter.”

Three of the animals sustained nonfatal liver lacerations, allowing researchers to better understand how live tissue responded to blunt blows to the liver under a variety of conditions. All the pigs survived the experiment, but were eventually euthanized so their organs could be studied.

Grisly though some of the experiments might be, they get closer to simulating the real effects of body armor blows on live personnel. By comparing the experiments with the indenter on unarmored pigs and parallel live-fire tests on armor-wearing cadavers, McEntire believes engineers can design with much greater confidence.

“We can calculate the energy, we can calculate the impulse, the momentum, the deformation,” he said. “That’s one of their tasks, is to help us identify which metric is the best predictor, which best correlates with injury and then ... the different severities of injury you can have.”

And he’s already expecting other entities to benefit from the Army’s research. The National Institute of Justice, the regulating agency for law enforcement body armor, will have access to the BABT findings, McEntire said.

The automotive and athletic gear industries, among others, may also benefit from the work, he added. But McEntire said he’s most motivated by the impact he hopes to have on future combat troops.

“If we’re successful, and can get this out and get it transitioned to the material developers,” McEntire said, “then I’ll be touching every soldier for the next 50 years who wears body armor.”