It has been more than a year and a half since the military opened all jobs across the services to women.

But for jobs in the Navy’s special warfare community, including SEALs, getting women into the ranks of their elite career fields has been slow.

To date, there is only one enlisted female in the accession pipeline to potentially become a special warfare combatant-craft crewman, or SWCC, according to Naval Special Warfare Command spokesman Lt. Cmdr. Mark Walton.

Whether the woman makes it is unclear — the accession pipeline for the special warfare job involves months of standard Navy training before the candidate even enters the formal schooling and testing.

Yet the SEALs are not the only Navy job where the presence of women continues to be rare.

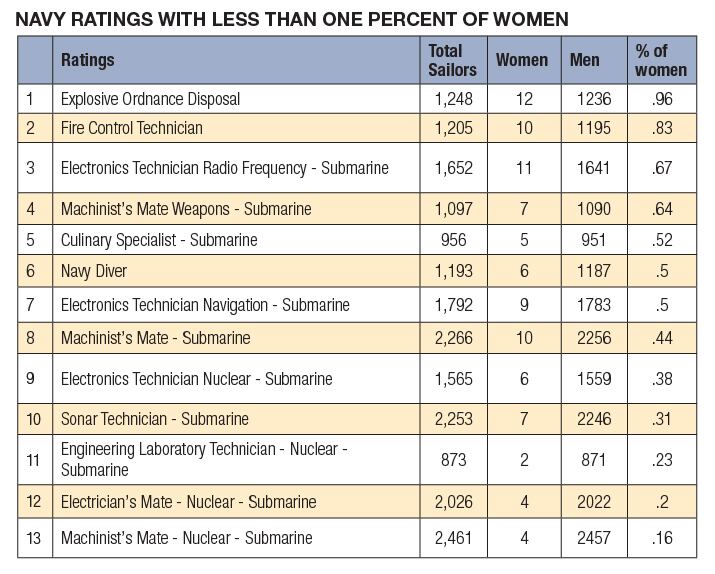

Navy data shows there are 13 ratings where women make up less than 1 percent of sailors, including more physical, combat-oriented jobs like navy diver and explosive ordnance disposal.

It remains unclear precisely why women are not moving toward such jobs in greater numbers after the Pentagon eliminated all formal gender restrictions across the force last year.

Part of it could come down to culture. Throughout Navy history, female sailors blazing a new trail have faced pushback entering previously all-male jobs, as was the case with assignments to surface warships or becoming pilots.

And while Navy leaders seek to expand the number of women in the ranks, female sailors in some ratings say their gender has hindered their advancement.

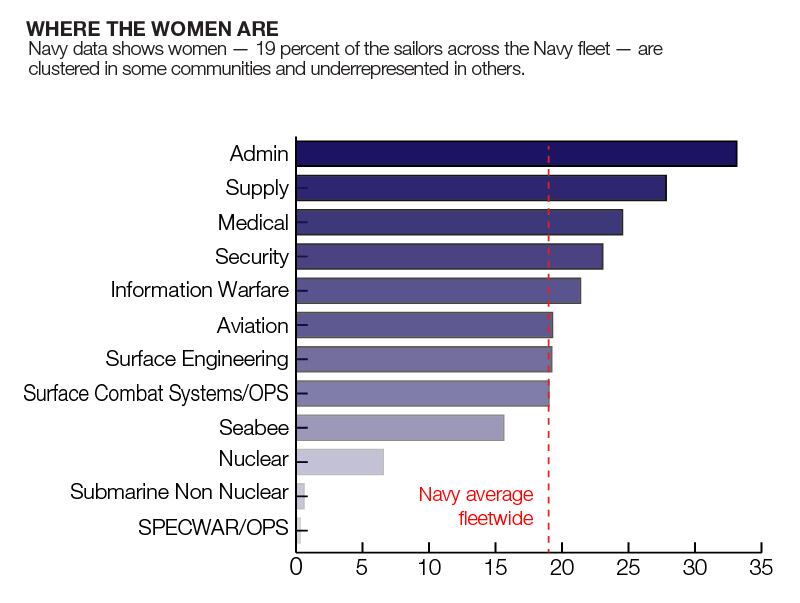

Today, about 19 percent of the enlisted fleet — roughly 50,500 sailors — are women, and the sea service wants to increase that presence to 24 percent by 2025.

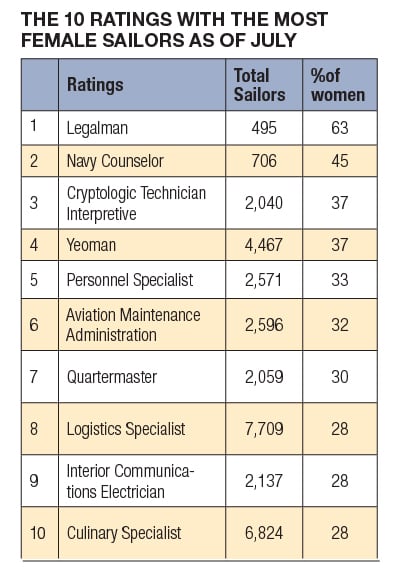

Personnel data shows women comprise the majority in only one rating: Legalman, where they make up 63 percent of the field’s 495 sailors.

Women make up 45 percent of the Navy counselor rating, and 37 percent of interpreters and yeoman, according to personnel data.

They also comprise about 33 percent of personnel specialists.

Navy officials concede that some jobs may remain nearly all-male.

“History tells us that, though the opportunity is there to take those tough jobs, most women choose to serve elsewhere,” said a Navy personal official familiar with efforts to recruit and retain more women.

LIMITED OPPORTUNITIES

Not all physical, combat-related Navy jobs remain completely devoid of women.

Since all gender restrictions were lifted in January 2016, at least 36 women have qualified in a variety of riverine enlisted classifications, according to Navy officials.

Yet those ambitious enlisted women sailors say their advancement opportunities are limited.

Mineman 1st Class Rebecca Cross enlisted 17 years ago and has resigned herself to the fact she will likely retire as a first class.

“The upward mobility just isn’t there,” Cross told Navy Times. “We haven’t had a female mineman make chief in over four years.”

Cross wants to go to sea, and knows she needs to go to sea to be competitive as she nears the senior enlisted realm.

But women in the Navy face a lack of berthing, Cross said, and their careers suffer for it because that makes it harder to land the sea tours they need to move up.

“I don’t want to be given anything different than men,” she said. “I just want opportunity that is equal to what the men have… I can compete with them if I am given the same opportunity to qualify in career-enhancing billets.”

The shortage of racks is a reality the Navy concedes on its “Women on Ships” website.

“Rack allocation is based on the total number of women currently assigned for pay grades E6 and below or E7 and above,” according to the site. “So, there might be a time in your career that the detailer will tell you that they have no ships or there are no open racks on their requisitions.”

Navy data shows women like Cross leave the sea service as the ranks advance.

Women make up a quarter of sailors in the E-1 through E-3 ranks, according to Defense Manpower data.

But the percentage of women in the ranks drops to 18 percent at the mid-level E-4 to E-6 levels and shrinks to less than 7 percent at master chief.

Career fields with few women may offer less opportunity for mentorship, and job demands might require more deployments or time at sea. Such aspects make jobs less family friendly, an issue the Navy believes is a top concern for women.

“We just don’t retain as many women as we’d like after the first or second enlistment,” the Navy personnel official said. “We lose them at a higher rate than men and it’s something we’ve studied and are making progress at fixing, though not as fast as we’d like.”

HARD TO BE FIRST

The woman training this summer with sights set on career as a SWCC was not identified by Naval Special Warfare Command officials due to “operational security realities,” Walton said.

On the commissioned side, one female Naval Academy midshipman who entered the accession pipeline to become a SEAL, a journey in which countless men have failed over the years, has opted out.

Retired Navy Capt. Lory Manning, now director of the Service Women’s Action Network, said it may be too early to glean any firm takeaways from the lack of women entering the pipelines to special warfare.

Culture, physical standards and the enormous reality of being first might explain the lack of women so far, she said.

Pioneering women who led the way into a variety of Navy jobs over the past decades have faced pressures and seen their careers impacted by old biases, Manning said.

“I don’t know that a lot of 19-year-olds realize that, but it’s very scary to go first,” she said. “There are real dangers there.”

Adding to that is the daunting physical standards, Manning said.

“When I was in the Navy, I knew a lot of men who couldn’t get through BUD/S,” she said of the grueling Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL training.

How welcoming the special warfare community will be to those female brethren who can physically hang remains to be seen, Manning said.

While some Navy watchers have warned that integration of the SEAL ranks will be impossible, Manning pointed out that SEALs have operated with female linguists and intelligence experts for years.

“The culture may turn out to be more welcoming than some people think,” she said. “It has to be watched.”

Instructor subjectivity and potential bias, either for or against a female candidate, in such intense training programs will also need to be tracked.

Training in areas like small-unit tactics involves instructors making subjective judgements as to the leadership fitness of a candidate, Manning said, and those conducting the training must be aware of gender influencing their assessment.

“What’s my idea of a combat leader, if I’m doing the judging,” she said. “It’s got to be looked at not just from, are they meeting the physical standard, but are those evaluating them fairly evaluating them?”

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.

Mark D. Faram is a former reporter for Navy Times. He was a senior writer covering personnel, cultural and historical issues. A nine-year active duty Navy veteran, Faram served from 1978 to 1987 as a Navy Diver and photographer.