MARIETTA, Ga. — “I really have had a good, good life,” said Tess Gay on Sept. 14 as friends and relatives stopped by her Marietta home to celebrate her 100th birthday.

Gay held court from her comfy living room chair wrapped in a golden boa with a matching crown with the number 100 on top. Each time a new loved one entered, she smiled big and welcomed them with a hug. Guests milled about, munched on hors d’oeuvres and posed for selfies with the new centenarian.

Gay is the widow of George Gay, a Navy pilot and decorated hero of the Battle of Midway.

Tess Gay grew up outside Washington, D.C., in a military family. She said she had a pleasant childhood growing up on a naval base where she was insulated from the nation’s financial troubles.

“We didn’t feel the Depression as much as most people,” she said. “We didn’t feel it so much because we lived on a naval base and everything was taken care for you there.”

After graduating high school, Gay stayed in the D.C. area to attend college at Strayer University, which was at the time called Strayer’s Business College, in Herndon, Virginia.

She said her life changed once the U.S. entered World War II following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

“I was stunned,” she said. “A friend of mine’s husband was called to serve right after Pearl Harbor. They rounded up all the Japanese. It was pretty frightening, and she didn’t see her husband for three days when they were out doing the Japanese round-ups, which I felt were very unfair at the time, because many of them were very innocent.”

Six months after Pearl Harbor came the Battle of Midway, where the U.S. issued the Japanese Imperial Navy a staggering defeat in what would turn out to be one of the war’s most decisive battles.

George Gay, then an ensign, was a pilot assigned to Torpedo Squadron 8, which was tasked with sinking Japanese vessels.

Under withering enemy fire from machine guns and anti-aircraft batteries, Gay continued to press his attack on a Japanese carrier. He pressed on even after his rear gunner Radioman 3rd Class Bob Huntington was killed and another machine gun bullet struck his own left arm.

When Gay went to fire his torpedo for the first time in his life, nothing happened. The controls had been shot out.

His left hand temporarily useless, he held the plane’s control stick with his knees while he reached back and pulled the emergency release cable. He made a hard turn to avoid the anti-aircraft weapons on the carrier, but his plane was hit by enemy fighters and he realized he was going down as flames started to lick at his left leg.

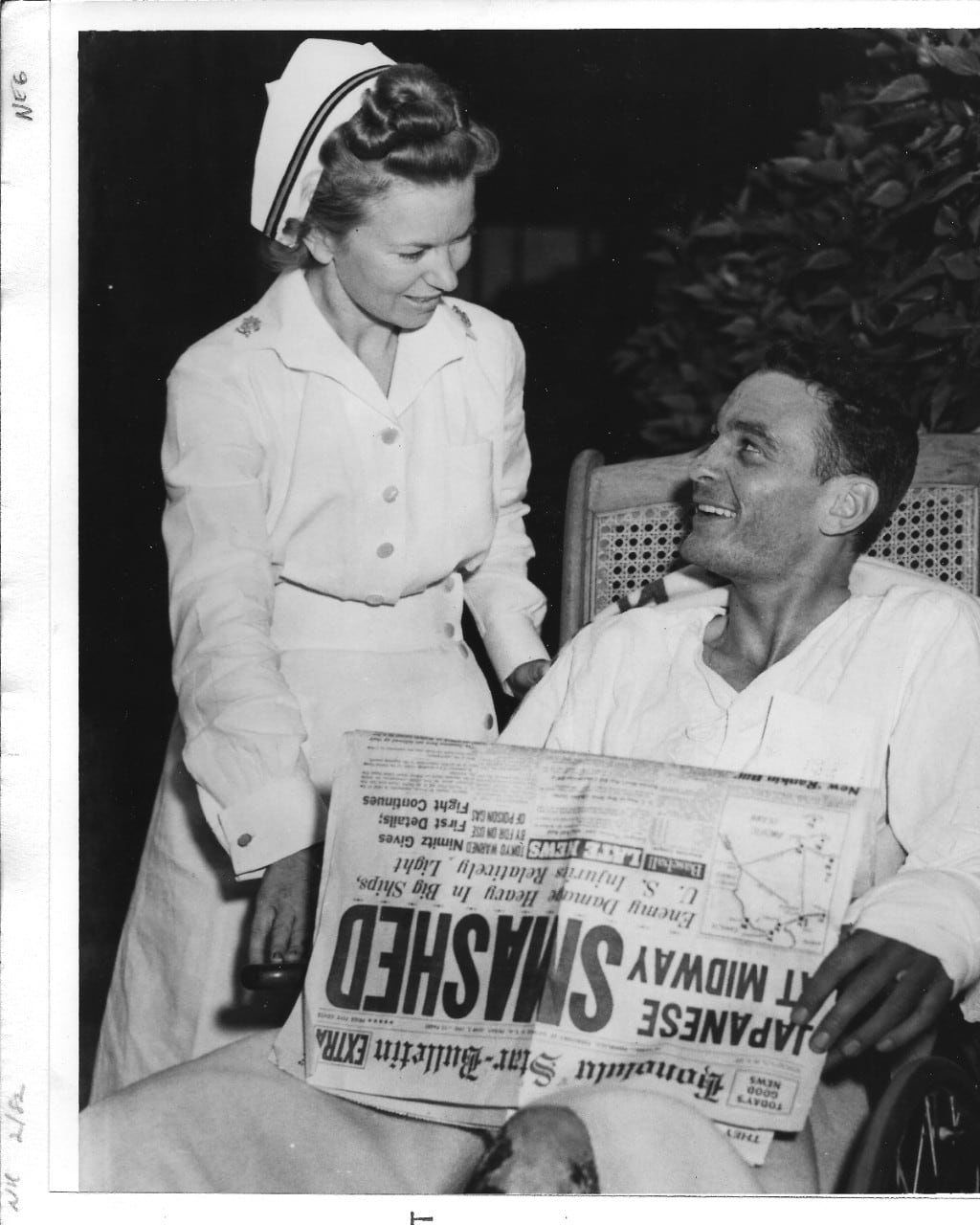

The wounded ensign spent 36 hours in the ocean as the battle raged on around him, hiding from enemy fire beneath a black seat cushion until he felt it was safe to inflate his life boat. He had what accounts called a “ringside seat” for the remainder of the fighting and personally witnessed three burning Japanese carriers slip under the waves.

His decorations include the Navy Cross, Air Medal, Presidential Unit Citation Ribbon with blue star and Purple Heart Medal.

Gay quickly became a celebrity after his rescue. He was hailed as the sole survivor of his squadron.

In reality, he was the sole survivor of the planes based on his carrier.

Two squadron members from a different carrier — Ensign Albert K. “Bert” Earnest and Airman 3rd Class Harry Ferrier — also survived the battle.

In total, 45 of the 48 men of Torpedo Squadron 8 were killed in action during the Battle of Midway.

(See editor’s note below)

With the public eager to hear about a victory after Pearl Harbor, his picture was in nearly every newspaper, songs were written about him, and he even appeared on the cover of Life Magazine.

But Tess Gay said the first time she met her future husband, she had only a vague idea of who he was.

“I was rooming with this friend, Scarlet, and she came home one night and she said ‘We’ve got an invitation to go to George Gay’s birthday party.’ I said ‘Who’s George Gay?’ ‘Oh, you know, he’s the one that’s been in the paper,’” she said. “They put me in the backseat sitting right behind George, who was the driver of the car. I remember him looking up at me and saying ‘Where have they been keeping you?’”

Looking back, Tess Gay said she loved him from the start.

“I loved everything about him,” she said. “It wasn’t perfect, I don’t mean that, but I just liked his way of doing things. And I must have liked him for 50 years.”

A few days after meeting him, she got a phone call. He was interested, too.

“The first thing he said was 'Now, before we start, he said ‘I’m not engaged with Scarlet, she was just along for the ride, so I don’t want you to think I’m sneaking around,’” she said. “That was George. He was always right down to the nail.”

She said she didn’t really know what he had been through until the first time she met his mother.

“It just flabbergasted me, for him to be out in that ocean for 36 hours,” she said. “Only George Gay was the type that could do it, though. If he set his mind to do something, he did it.”

They were married in 1946 and lived in Marietta while George Gay worked as a captain for Trans World Airlines for over 30 years. They have two children, two grandchildren and one great-granddaughter.

Tess Gay said she remembers those years as some of the happiest of her life.

“We traveled quite a bit on little side trips, we called them, when he wasn’t flying. . . . For our anniversary, he came home one time, he said ‘We’re going to Europe, to Paris this weekend, for our anniversary.’ We went over, we had champagne, we had a celebration, and we came home the next night. We went on a date in Paris,” she said.

The couple traveled all over the world, to London, Paris, Rome, Athens, Cairo, Bangkok and more. Gay said her favorite places were Athens and Paris.

For the rest of his life, he would attend and speak at events commemorating the battle. Tess Gay, too, regularly traveled to Washington to attend Battle of Midway ceremonies following her husband’s death.

After George Gay died in 1994, his ashes were scattered in the ocean where he fought and bled.

RELATED

Miracle at Midway?

Uniformed representatives from the Navy came to her Marietta party to drop off birthday wishes from Secretary of the Navy Richard Spencer.

Other luminaries sent well-wishes by mail, including both of Georgia’s U.S. Senators, American Legion Commander James Oxford and Marietta Mayor Steve Tumlin, who honored the couple in 2012 by naming June 4 Tess and George Gay Day in Marietta, marking the Battle of Midway’s 70th anniversary.

Gay had a little fun with one of the sailors and asked if she could try on his uniform hat. Party guests laughed as she cocked it to one side, saying “Just like George wore his.”

Granddaughter Terri French, who lives in Oklahoma and hosts haunted historical tours, said her grandparents were role models for her growing up.

“She was very strict, very by-the-book. Pop Pop kind of spoiled me a little too much, and she didn’t like that,” she said with a laugh.

“I got to travel with them a lot growing up, I got to go to different air shows and see him speak, I got to go on the road with them quite a few times. . . . She has always had an air of class around her that I tried to emulate. I’ve always tried to be as proper and upstanding as she is. It’s a tough act to follow, but I’ve always tried.”

Tess Gay said what other people call class is a matter of respecting oneself, something she thinks today’s youngsters could learn to do better.

“The Bible says ‘People will cry for peace, but there will be no peace,’” she said. “That’s what’s going on in the world today. . . . and teenagers today are so unlike we were when we were growing up.”

But that doesn’t mean eschewing fun, either. Ask her the secret to a long, happy life, and she’ll tell you to set aside a little time to relax.

“You want the truth? A martini every day at five o’clock,” she said with a laugh. “One, mind you, just one.”

Navy Times editor’s note: It’s true that Ensign Gay was assigned to VT-8 on the aircraft carrier Hornet (CV-8) and he was the only survivor from his detachment, but I don’t believe this story is correct about Earnest and Ferrier flying from another carrier.

First of all, there were three men in their plane. The pilot was Ensign Albert K. Earnest and his crew were Radioman 3rd Class Harrier H. Ferrier and Seaman 1st Class Jay D. Manning, the .50 caliber machine gun turret operator.

Manning died while engaging Japanese fighters during the 4 June 1942 attack and Ferrier was seriously wounded.

They didn’t launch from another carrier. They flew from Midway Island.

Six TBFs from VT-8 (not the obsolete Douglas TBD Devastators on the Hornet) arrived at the last moment.

They’d been left behind in Norfolk because Hornet was taking Lt. Col. Jimmy Doolittle’s B-25 bombers for their daring raid on Japan.

The TBF crews trained in their new planes before making their way independently to Oahu. Those Avengers were flown to Midway as part of the buildup before the Japanese closed on the island (to make it even more confusing, the bulk of the Avenger detachment missed the Battle of Midway because they were in Hawaii; they caught up to what was left of the squadron at Guadalcanal).

Gay never said he was the only member of the squadron to survive the battle. He always pointed out that the other detachment was in the thick of the melee.

If you have the time, read about the heroism of Earnest, Ferrier and Manning, too.