The other day I went into Costco to buy some toilet paper. It came as a small shock when I couldn’t find a single roll.

The new coronavirus is inspiring panic buying of a variety of household products such as toilet paper in cities across the U.S. and world.

While it makes sense to me that masks and hand sanitizer would be in short supply because of the outbreak, I wondered why people would be hoarding toilet paper – a product that is widely produced and doesn’t help protect from a respiratory virus like COVID-19. Toilet paper is becoming so valuable there’s even been at least one armed robbery.

As an economist, I am fascinated by why people hoard products that are not having supply problems. Toilet paper hoarding in particular has a curious history and economy.

Past panics

This wouldn’t be the first panic over toilet paper.

In 1973, U.S. consumers cleared store shelves of the rolls for a month based on little more than rumors, fears and a joke.

At the time, Americans were already worrying about limited supplies of products like gasoline, electricity and onions.

A government press release warning of a potential shortage in toilet paper led to a lot of press coverage but no outright panic buying until Johnny Carson, a famous late night television host, joked about it during his opening monologue. Instead of laughing, people took it seriously and began to hoard toilet paper.

Americans aren’t alone in panic buying to ensure they have plenty of squares to spare. Venezuelans hoarded the commodity in 2013 as a result of a drop in production, leading the government to seize a toilet paper factory in an effort to ensure more supply. It failed to do the trick.

100 rolls a year

The average person in the U.S. uses about 100 rolls of toilet paper each year. If most of it came from China, this could be a huge problem because supply chains from that country have been severely disrupted as a result of COVID-19.

The U.S., however, imports very little toilet paper – less than 10 percent in 2017. And most of that comes from Canada and Mexico.

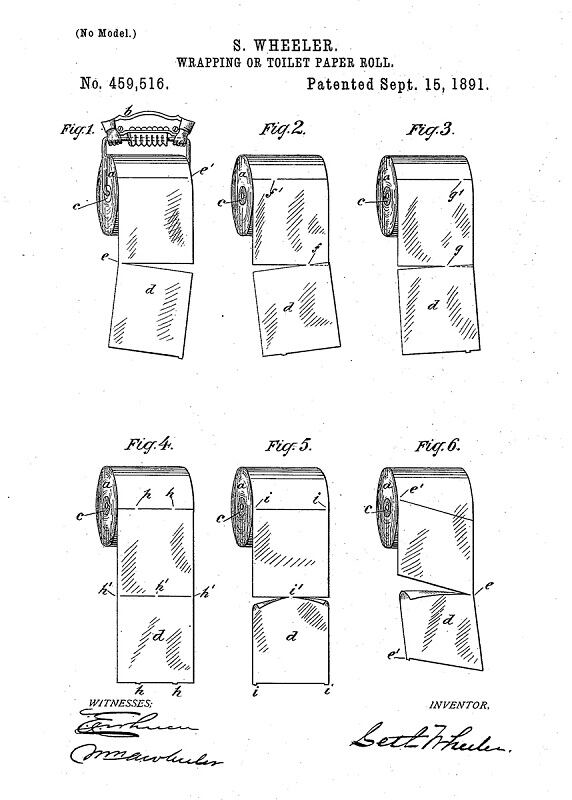

The U.S. has been mass producing toilet paper since the late 1800s. And while other industries like shoe manufacturing have fled the country, toilet paper manufacturing has not.

Today there are almost 150 U.S. companies making this product.

Why people hoard

So then why would people hoard a product that is abundant?

Australia has also suffered from panic buying of toilet paper despite plentiful domestic supply. A risk expert in the country explained it this way: “Stocking up on toilet paper is … a relatively cheap action, and people like to think that they are ‘doing something’ when they feel at risk.”

This is an example of “zero risk bias,” in which people prefer to try to eliminate one type of possibly superficial risk entirely rather than do something that would reduce their total risk by a greater amount.

Hoarding also makes people feel secure. This is especially relevant when the world is faced with a novel disease over which all of us have little or no control. However, we can control things like having enough toilet paper in case we are quarantined.

It’s also possible we are biologically programmed to hoard. Birds, squirrels and other animals tend to hoard stuff.

How to handle shortages

There are a number of ways to handle shortages, including those caused by hoarding.

The best way is to convince people to stop doing it, especially with plentiful products like toilet paper. However, logic often fails when dealing with emotional issues.

Another way is by rationing. Formal rationing is when governments allocate goods by specifying exactly how much each family gets. The U.S. used rationing during World War II to allocate gasoline, sugar and even meat. China rationed a lot of goods including food, fuel and bicycles until the 1990s.

Sometimes businesses enforce informal rationing. Stores prevent customers from buying all they want. The Costco I went to for toilet paper had a sign limiting shoppers to five packages per customer.

Modern economies run on trust and confidence. COVID-19 is breaking down that trust. People are losing confidence that they will be able to go outside and get what they need when they need it. This leads to hoarding items like toilet paper.

While the government advises preparing for a pandemic by storing a two-week supply of food and water, there’s no need to hoard stuff, particularly products that are unlikely to suffer from a shortage.

As for my local Costco, I stopped by a few days later, and the toilet paper aisle was fully stocked.

Dr. Jay L. Zagorsky is a senior lecturer in Markets, Public Policy and Law at Boston University’s Questrom School of Business. He’s published frequently in scholarly journals and also wrote the books Business Information: Finding and Using Data in the Digital Age and Business Macroeconomics: A Guide for Managers, Traders and Practical People.