When Louis “Lou” Conter enlisted in the U.S. Navy in 1939, he was bracing for the U.S. to get involved in World War II — he just didn’t know when.

That’s why when he was a third-class quartermaster assigned to the battleship Arizona, there was no doubt in his mind the morning of Dec. 7, 1941 what was going on: the United States was under attack.

“We knew immediately they were Japanese planes,” Conter, who was 20 years old at the time, told Navy Times.

As the quartermaster on watch that morning on the quarterdeck, he remembers when the fourth bomb struck the Arizona and punctured through five decks. The bomb prompted a massive explosion, and caused the ship to go down 14 minutes after the first sighting of a Japanese plane.

There was no time to process what had just happened, according to Conter, and those who survived the explosion were then responsible for assisting wounded survivors from the water as rescue operations got underway.

Despite the tragedy of the attack, Conter stressed that everyone did exactly as they were supposed to in response to the attack.

“We were highly trained for everything that happened,” Conter said.

Nearly 80 years after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Conter, 99, is one of two remaining survivors from the battleship Arizona. And now his story is being recounted in a new book.

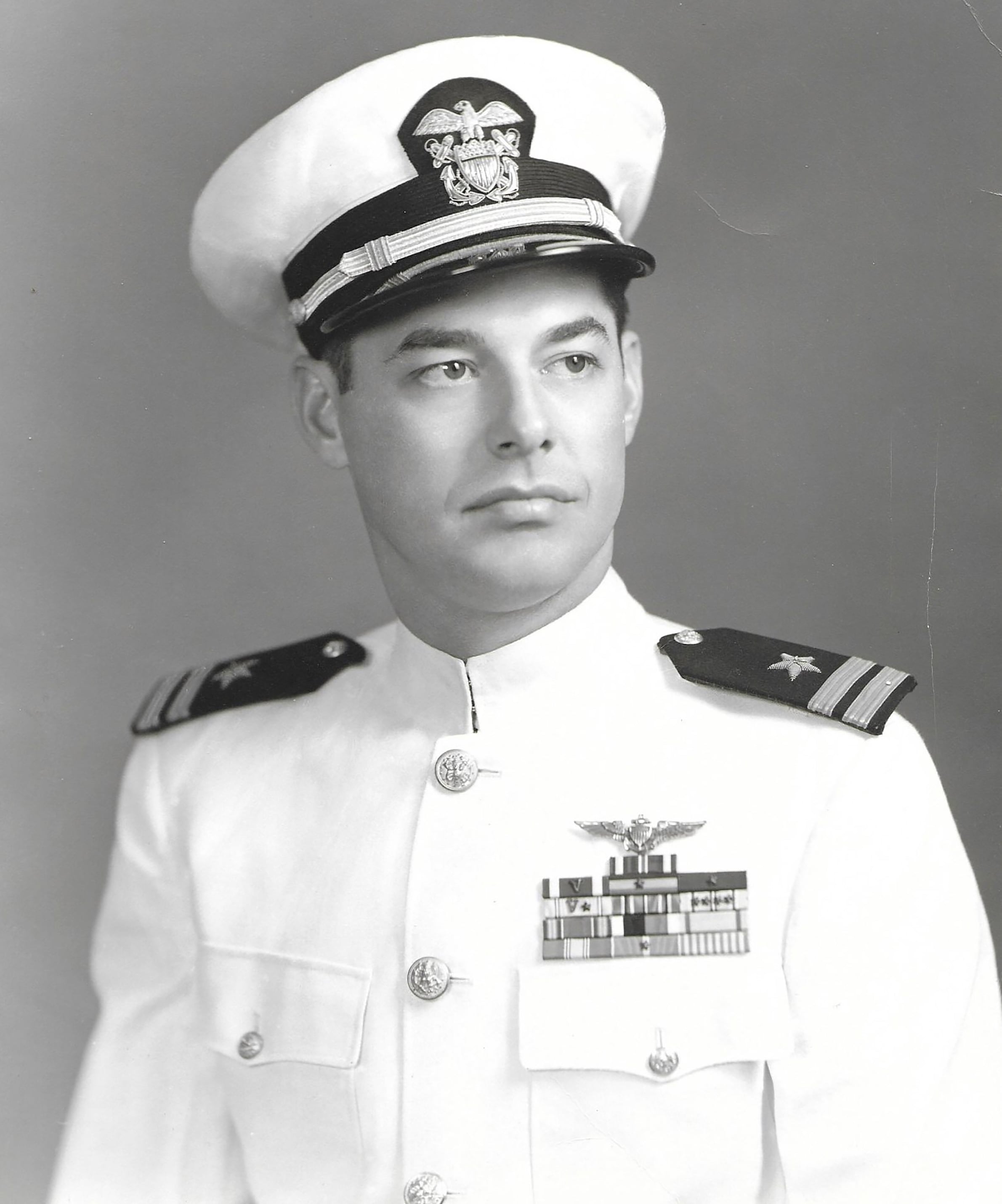

From becoming a Naval aviator and an intelligence officer, to crafting the Navy’s Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape program, “The Lou Conter Story” chronicles Conter’s military career, survival tips, and anecdotes of interactions with celebrities like Shirley Temple and Bob Hope.

The book, which was released in January, was co-authored by Annette and Warren Hull. They initially interviewed Conter in 2018 for a documentary film they were producing about the Arizona’s band, “A Band to Honor.” Conter is also featured in the documentary, and puts to rest claims that the Arizona’s band died in their sleep.

“A lot of stories came out and said they were in their bunks asleep since they played in the Battle of the Bands the night before — that was a lot of bull,” Conter told Navy Times. “They went to their battle stations, they were all killed at their battle stations.”

The Hulls, who have their own independent film company called AnnWar Productions based out of Las Vegas, quickly became interested in Conter’s story as well, and moved forward writing a book that recounts his life.

A Navy Career

In January 1942, Conter was headed to Pensacola, Florida to complete flight school through an enlisted pilot training program. Afterwards, he was assigned to Patrol Squadron 11 to fly the PBY Catalina “Black Cats,” and eventually became a commissioned officer.

During his aviation career, he flew missions during World War II in the Southwest Pacific, and survived being shot down on two occasions. The first time, he and the crew were stuck roughly seven miles off the coast of New Guinea and were forced to tread water in the dark and in shark-infested waters.

Even though some of the other men cast doubt on their ability to ward off the sharks, Conter didn’t let it phase him. Instead, he instructed the men to gently tread water and smack any approaching sharks on the nose with a fist.

“The sharks did come, but just as I said, as soon as we hit one of them in the nose, it would turn the other way and swim away really fast,” Conter wrote in the book.

Thanks to Conter’s instruction, the men all survived until they could be rescued.

Among his awards during his service in WWII are the Distinguished Flying Cross for Valor, which he earned for participating in flights in the Southwest Pacific in 1943 to assist rescuing more than 200 Australian Coastwatchers in New Guinea.

Given his experiences, it’s clear Conter is no stranger to survival in rough conditions. So after completing special forces training under Col. Aaron Bank and escape and evade training, Conter became one of the first survival, evasion, resistance, and escape (SERE) officers in the U.S. Navy, and was involved with creating the Navy’s own SERE program in the 1950s.

The program was specifically tailored to Navy pilots and their crew so they could survive in the event they were shot down.

“We had to teach them how to live in the jungle...how to hide in the jungle, how to navigate, and how to get out alive,” Conter told Navy Times. “And we did that.”

“Above all, don’t panic in any situation you are given in life,” Conter said.

In the book, Conter outlines the eight principles for survival: size up the situation; undue haste makes waste — have patience; remember where you are; vanquish fear and panic; improvise; value living; act like those around you — live with the natives; live through being well trained — learn basic skills.

“Survival is difficult, but one has only two options if put in a survival situation: give up and die or fight like hell and live,” Conter wrote in the book.

Following complaints from mothers to lawmakers about the brutal nature of SERE training, which was also designed to prepare troops to survive POW camps, then-Cmdr. James Stockdale from the Bureau of Personal Navy Aviation came to check out what SERE training was all about.

Stockdale, who participated in the training incognito, ultimately concluded that the training was rough and the most difficult he had ever undergone, but praised its benefits, Conter wrote.

Unfortunately, Stockdale was forced to implement the training after he became a prisoner of war during the Vietnam War. Stockdale, who was held in captivity at the “Hanoi Hilton” POW camp for more than seven years, was later awarded the Medal of Honor in 1976.

According to Conter, Stockdale credited his survival to the challenging nature of SERE training and called Conter after he returned to the U.S in 1973 to tell him he wouldn’t have survived without it.

“And so I said, ‘Jim, if one person can tell me that, to hell with the mothers and the congressman — I’ll train the guys how I feel they need to be trained so they get back home alive,’” Conter told Navy Times.

After a total of 28 years in the Navy, Conter retired in 1967 at the rank of lieutenant commander — the highest rank he could achieve as an officer without a college degree. His long career in the Navy took a toll on his first two marriages, and although he said he has no regrets, he admitted that his marriages and military career were “two elements of my life that just never seemed to get along very well.”

Conter has three children from each of these marriages, and says he considers having these six children his “greatest accomplishment.”

After he retired, he was married to his third wife Val for more than 45 years before she died due to lung cancer. Conter currently lives in Grass Valley, California.

Returning to the Arizona

When Conter returned to Hawaii in 1951, the USS Arizona Memorial hadn’t been stood up, but there was a platform over what was left of the battleship. Despite heading out to the Arizona on a barge with the intention of visiting the platform, Conter said he was overwhelmed with emotion and memories and decided to remain on the barge and offer a salute.

“All of them didn’t get to come back and get married, have kids, and grandkids and great-grandkids like we did,” Conter told Navy Times, explaining that he said a prayer for those those who lost their lives.

It wasn’t until the mid-1960s — Conter’s estimate is 1964 — that he returned to Hawaii to see the USS Arizona Memorial and entered the shrine room, which has the 1,177 names of those who lost their lives etched on a wall. Conter said seeing the wall for the first time “nearly took my breath away and knocked me out,” according to the book.

“I reflected for a moment about how easily my name could have been on that wall and wondered why it was not,” Conter wrote.

Since 1991, Conter has regularly attended Pearl Harbor Remembrance Ceremonies on Oahu. In fact, more and more family and friends started joining Conter for the remembrance ceremonies — earning them the nickname the “Conterage.”

Although he was unable to visit Hawaii in December 2020 due to COVID-19, he fully intends on doing so in 2021 if possible — even though he will be 100 by December 2021.

“I’ve got my reservations at the Hale Koa already...it’s a matter of God keeping me alive until then so I can go,” Conter told Navy Times.

Despite Conter’s military achievements — from rescuing shipmates during the Pearl Harbor attack to surviving being shot down twice — he maintains he was simply doing his job.

“I just did what I was trained to do,” Conter said. “I wanted to do the best job I could. And I’m no hero, I just helped do what I could do.”