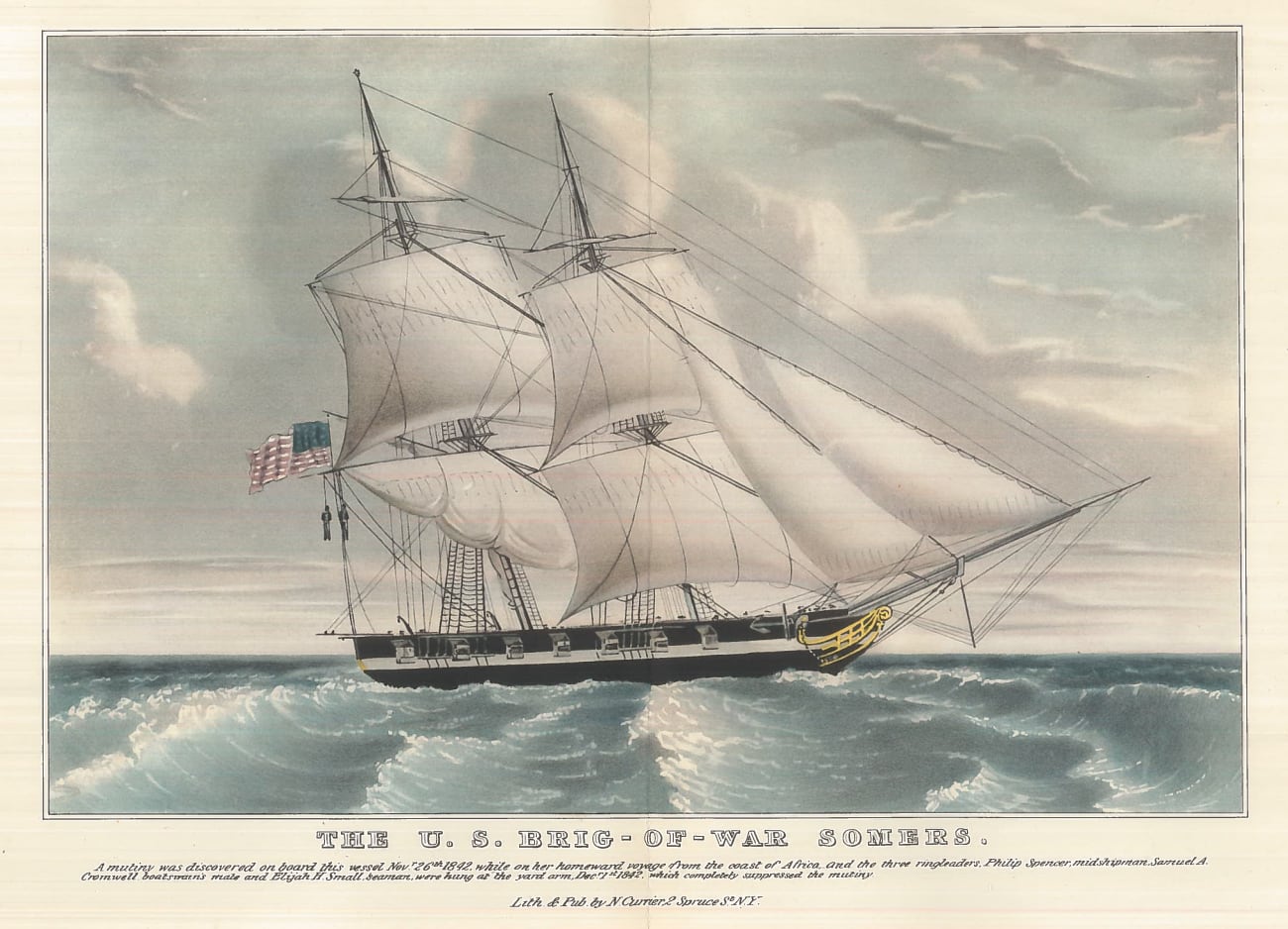

When Navy Cmdr. Alexander Slidell Mackenzie and the crew of the brig-of-war Somers pulled into Brooklyn Harbor in December 1842, he arrived with an alarming report: his crew had just barely escaped a mutiny.

Mackenzie reported that he had quashed the mutiny and prevented the slaughter of his crew by hanging the three mutineers: Acting Midshipman Philip Spencer, the alleged ringleader, and his accomplices, Boatswain’s Mate Samuel Cromwell and Seaman Elisha Small.

In turn, he received a hero’s welcome, with the New York Herald comparing Mackenzie’s actions to those found in the “early history of the Roman Republic.”

But the praise didn’t last, and conflicting accounts of what went down aboard Somers began to emerge, ultimately sparking a chain of events that would lead to one of the biggest and largely untold controversies in the Navy’s history and the creation of the U.S. Naval Academy a few years later.

The story of the Somers’ cruise and the subsequent fallout are detailed in “Sailing the Graveyard Sea: The Deathly Voyage of the Somers, the U.S. Navy’s Only Mutiny, and the Trial that Gripped the Nation,” which was released Nov. 21.

RELATED

Pirates of the Revolution

Days after the Somers arrived in New York reporting the attempted mutiny, a letter appeared in the Madisonian newspaper — a partisan mouthpiece of then-President John Tyler’s administration — and offered a very different account of the incident.

The letter was penned by the mutiny ringleader Spencer’s father, who happened to be Secretary of War John C. Spencer.

He claimed the mutiny allegations were “wholly destitute of evidence,” according to the book, elevating the Somers’ travails to a high-profile status in the process.

Secretary Spencer’s counter-claims would amount to little more than a dad sticking up for his son, but his weighing in on the incident helped capture America’s attention, the book’s author, Richard Snow, told Navy Times.

“[Philip Spencer] was a midshipman, and by God, he turned out to be the son of the Secretary of War,” Snow said. “So you knew now this wasn’t going to be some quiet story…this was going to gather momentum.”

The incident became the greatest scandal New York City had witnessed in years, and naval historian Samuel Eliot Morison claimed no other incident in the 19th century aroused such passion in America, outside of President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, according to the book.

‘Nothing alarming, at first’

Midshipman Philip Spencer commissioned in 1841 and joined the crew of the Somers in August 1842 — just a few months before he’d be accused of mutiny.

The ship was a sort of training ground for prospective sailors, according to the Naval Academy, and Midshipman Spencer’s obsession with pirates and their ways of life soon became evident, as he would regularly ask shipmates to share their best pirate stories, according to the book.

“There was nothing alarming at first,” said Snow, an author of several books who previously served as the editor-in-chief of American Heritage magazine. “But as they got further and further away from shore, he became more and more reckless in what he’d say and do. And he started talking about how his ship, the Somers, would make a great pirate ship.”

While some crew members reported to Mackenzie that Spencer discussed pirates and plans to take over the ship, the skipper initially brushed off such claims.

“Anxiety began to crackle through the ship,” Snow said.

Although Snow said Mackenzie wrote very detailed accounts of his life, no reason is expressly given for why he suddenly took Spencer’s pirate aspirations seriously and came to believe his ship was under siege.

Either way, on Nov. 26, Mackenzie ordered that Spencer be placed in double irons on the quarterdeck on charges of intended mutiny. Small and Cromwell faced the same fate the next day, and on Dec. 1, all three were hanged without a court-martial, per Mackenzie’s orders.

A later inquiry and Mackenzie’s court-martial ultimately exonerated the captain, and Snow’s book details how the entire affair became a source of shame for the Navy.

However, Snow’s book also notes that the incident paved the way for the Navy to overhaul how it trained its officers, leading to the creation of the U.S. Naval Academy a few years later.

Before the grim circumstances of Somers’ cruise, the Navy had trained its sailors using a model similar to the one the British Royal Navy employed, Snow said.

“As far as training their officers went…it was basically throw them in the water and see if they can swim,” he said. “You drop somebody down with a bunch of sailors and hope he worked out alright.”

But according to the U.S. Naval Academy’s website, the incident aboard the Somers “cast doubt over the wisdom of sending midshipmen directly aboard ship to learn by doing.” Less than three years after the Somers’ voyage, the Naval School kicked off its first class with 50 midshipman.

In 1850, the Naval School became the U.S. Naval Academy and implemented a curriculum where midshipmen would spend the academic school year training at the academy and summers aboard naval vessels.

“Did any good come out of this?” Snow said of the Somers affair. “Well yes, there is…Almost exactly 100 years later, [Annapolis] proved to be the seabed of the mightiest Navy the world has ever known. And that was one very good outcome.”