Former Special Forces medic Jason Deitch is an open book — written in code.

It's not just the cryptic Latin verses scrawled on his forearm around the image of a skeleton; he says each of the 10 tattoos that cover much of his chest, back and arms tells an important story.

But if you want to know the stories, you have to ask him what they mean.

"Tattoos are a record or a journal of a veteran's experience — where they've been, what they've done, what they've seen, who they've lost," says Deitch, a sociologist who works with the Veterans Administration in San Francisco's Bay Area.

This fusion of ink, stories, and conversation was the genesis of a new "online exhibit" created by Deitch, designed to help bridge what he calls "the culture gap" between the military and civilian worlds.

The virtual gallery "War Ink" is a masterpiece of sight, sound and story — a mashup of words and photos, video and audio interviews, all presenting the personal narratives of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in their own words.

"There is this rigid barrier between the military and civilian world that's grown over the last 40 or 50 years. There is no cultural understanding of military life. Most of the civilian world doesn't even have concepts for the kind of things we've seen and done," Deitch says.And on their bodies.

From the "War Ink" online exhibit, Air Force veteran Heather Hayes: "I don't regret any tattoos because they all represent that moment in my life. It's like a map of my journey. It's art that I get to carry with me forever."

Photo Credit: Johann Wolf

"But tattoos can present a doorway into that conversation. A civilian with the right intention can go up to a veteran and say, 'That's an amazing tattoo. Can you tell me about it?' You've just opened a conversation that's not happening in America."

Stunning, stark and sometimes darkly humorous, the exhibit is presented in four chapters: "We Were You," "Changed Forever," "Living Scars," and "Living not Surviving." All focus on 24 veterans and their roughly 100 tattoos.

"I wanted to create a primer on warfighter culture that also spoke directly to the civilian population about the authentic experience of a military at war," Deitch says of the website, produced in partnership with the Contra Costa County (California) Public Library.

But this website is like few, if any, you've seen before: equal parts video documentary, radio soundscape and magazine photo spread — more of an immersive journey than pages on a screen.

Winged boots, waiting in heaven

In the "Living Scars" section, Army veteran Noah Bailey describes the roadside bomb that ripped apart both of his legs and the agonizing three-hour wait for a helicopter that would get him to a field hospital.

He looks out at you against a white background, as if at parade rest. The photo is just his upper body, the faint outline of a tattoo peeking out from his grey Bob Marley T-shirt. In the audio clip playing in the background, he describes the dark struggle that followed.

"I got home, I got married, bought a house, got a divorce a year later," Bailey says as if rattling off a grocery list. His wife left him because he couldn't shake the depression. Then it just got worse.

"I was like rock bottom, had a gun in my mouth multiple times," he says.

He describes one of his tattoos. It sounds bizarre: a burning Humvee, rays of light from heaven, winged boots flying up from the wreckage.

The audio clip ends.

Scroll down and the image of Bailey pans seamlessly from his upper body, down below his waist to his missing legs and the black sneakers he now wears on two prostheses.

From the "War Ink" online exhibit, Army veteran Ryan Leva of Santa Cruz, Calif., who served from 2001-2008: "We have to go to extreme ways. I think it is really important for us to share a dialogue with the general public about our experiences overseas in order to bring a greater awareness about not only what we go through but also the struggles faced when we come back. I am pleased to have been a part of it."

Photo Credit: Johann Wolf

Scroll again and you finally see it, the black-and-white scene inked into his chest.

The boots, he says, "are like my feet going to Heaven. They're going to be waiting for me."

Safer shores

Some of the tattoos are simple, almost cartoonish. Many more are intricate pieces of art that could be painted on framed canvas as easily as inked onto living skin.

One of Victoria Lord's tattoos is somewhere between. The former Navy corpsman, who served in Iraq, has a Hello Kitty tattoo wearing a white "dixie cup" sailor's hat, flanked by two swallows. Covering much of her left arm, a tall, square-masted warship rises behind in raging waters, as if it has delivered her to safer shores.

"I owe the Navy my life," says Lord, who describes growing up in a broken family before enlisting.

"When I joined the military, and there was structure — there was a roof over my head, there was food on my table, and there were people who were going to stand behind me no matter what — it taught me the real meaning of family."

David Cascante, an Army infantryman, describes the jitters of going to war.

"There were times where definitely you wonder is today my day," he says as his image baring his tattooed arm fills part of the screen.

"This tattoo was done before I deployed," he says in the accompanying audio clip, describing the eagle perched atop a helmet and crossed infantry rifles. The eagle's spread wings represent freedom, he explains.

"In between the eagle and the smoke, there's an American flag, and it's kind of just indicative of, 'No matter how much freedom we have at any given point, you know always in the background in America there's some kind of conflict going on.' It's through the bloodshed — that's the price ... paid for freedom.

"I'm very much in love with it. I'm very much proud of it and what it represents for me."

'Larger than all of us'

From the "War Ink" online exhibit, active-duty Army and Army National Guard veteran Tracey Cooper-Harris of Los Angeles, who served from 1991 to 2003: "The majority of veterans want to do whatever we can to help out our fellow veterans. We want to be able to show that we are like any other person. We've been through some shit, lost friends and want to get back to making an impact on our world. That can't be done if folks don't understand where we're coming from, think we are people to be pitied, or that we'll be okay because the VA is taking care of us. I hope that this project can shed light on the incredible diversity of those who served and the common thing we all share: we are all humans. We're here to help each other."

Photo Credit: Johann Wolf

Iraq veteran Tracey Cooper-Harris says the project "was an amazing thing to be a part of."

The band of paw prints around her left biceps hints at her job in the Army serving as a veterinary aide, caring for military working dogs.

"It was a good way to remember the dogs, my patients, and recognize that I had this incredible job. A lot of people don't even know this type of job even exists in the military."

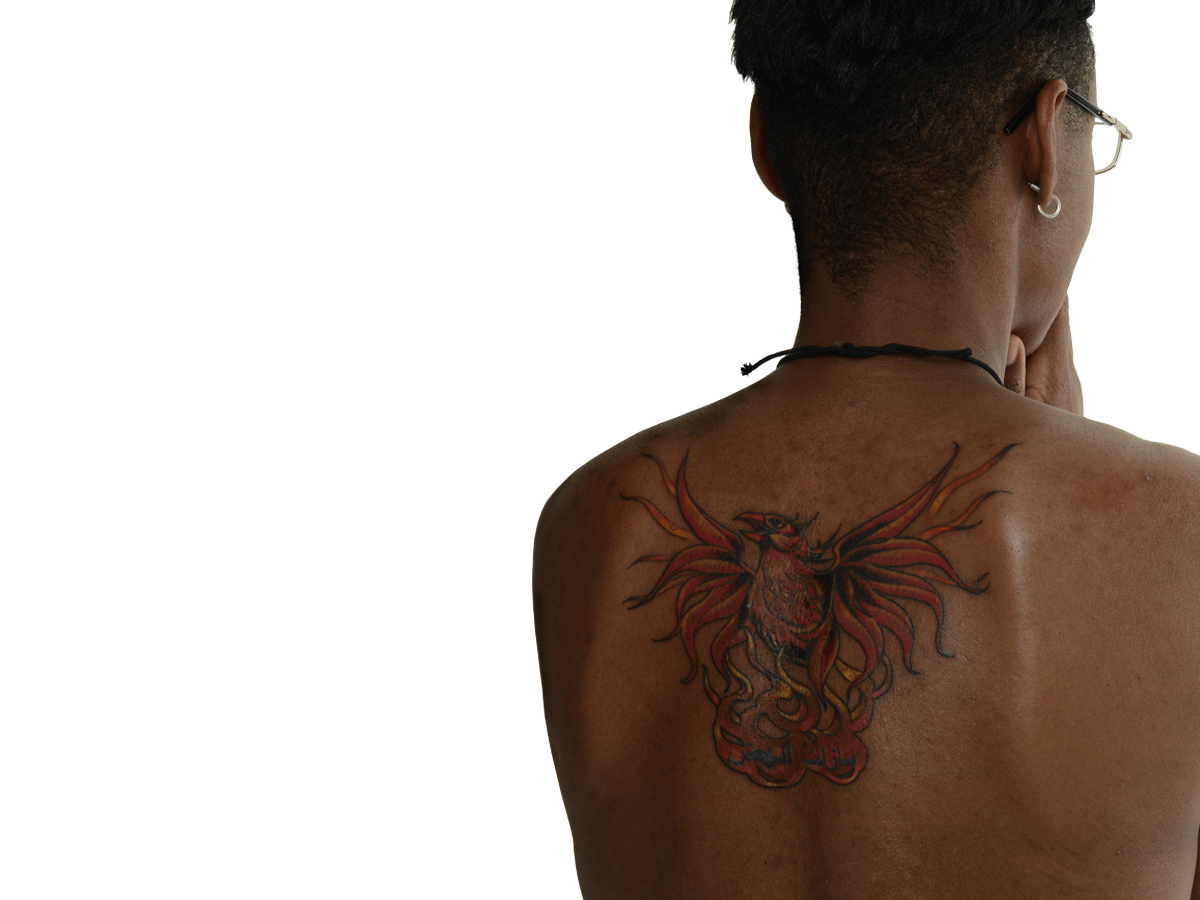

She got the idea for the stunning red phoenix on her back during a deployment to Iraq a few years ago, but got it inked just this summer.

"It symbolizes that even though it felt like everything was falling apart, I was still able to rise out of the chaos," she says. "Every time I feel like I'm about to crash and burn, I still rise."

The images and video were captured over a four-day shoot with award-winning photographer Johann Wolf and filmmaker Rebecca Murga, an Army Reserve officer.

"Sometimes it's easy to get caught up in the small things in life," Murga says. "Those four days reminded me of what is really important. One day, we will look back on those four days, and realize we did something larger than all of us.

From the "War Ink" online exhibit, active-duty Army and Army National Guard veteran Tracey Cooper-Harris of Los Angeles got the idea for her red phoenix tattoo during a deployment to Iraq.

Photo Credit: Johann Wolf

"It was emotional for me," she adds, not just because of the tattoos or the stories behind them, but because of the veterans themselves and their willingness both to show and tell.

"Some of them coming back to jobs they earned, others to empty apartments, some just trying to live another day. Not one of them asks for a 'thank you,' " Murga writes in her blog. "For one day, they felt beautiful, and happy, and understood. One frame at a time. And if that is all that ever comes of this project, I would be OK with that."

Deitch hopes the exhibit has a far wider reach.

In a section titled "Your Role," viewers are encouraged to reach out to veterans in their own communities.

From the "War Ink" online exhibit, Navy veteran Joel Booth of Temecula, Calif, who served from 2010 to 2013: "Just having this project brought together was an awesome highlight. I feel this project will help civilians have a better understanding of some of the culture that combat veterans are a part of. Tattoos tell our stories."

Photo Credit: Johann Wolf

"Whether a veteran is a close relative, a good friend, a co-worker or even a new acquaintance, ask about his or her experiences," it reads. "Most veterans welcome the opportunity to share their stories. And when they do, then ... listen. Really listen. Don't use the conversation as an opportunity for telling your own story or voicing your opinions. Just be open and respectful."

Of course, if there's a tattoo, you can start there.

The beauty of asking about a tattoo, Deitch says, is that it also leaves the veteran in the driver's seat: "This person has it on their skin, but they get to tell you how much — or how little — of that story they want you to know."

And if you ever happen to meet him, ask him about those cryptic Latin verses winding around the skeleton on his forearm.

It's a hell of story.