This final roundup of the publishing year includes famous names such as Grant and Hagel, and increasingly famous names such as Flo Groberg and Humayun Khan —men who show that immigrants serve their country, too.

Our nonfiction reviews, in order of reading value and satisfaction (fiction lovers, head here). Prices are provided by the publishers; you may find better deals as the holidays approach.

Grant by Ron Chernow, Penguin Press, 1,104 pages, $40.

Acclaimed with prizes including the Pulitzer, the author dedicates his new biography “to my loyal readers, who have soldiered on through my lengthy sagas.” This one, about the nation’s 18th commander in chief, falls in place.

With only 95 fewer pages than the Library of America edition of Grant’s own, originally two-volume “Personal Memoirs,” “Grant” weighs more than 4 pounds. Finishers merit a badge of courage labeled “read.”

Descriptions of secondary players (a cabinet member is “a tall, slim man with a balding pate, eyebrows that jutted over deep-set eyes, and a pencil-thin mustache”) are expendable. Given a first chapter called “Country Bumpkin,” subsequent reminders of Grant’s humble beginnings are tiresome.

And the frequent mentions of his proclivity for alcoholic binges could drive you to drink. The conclusion: In the end, “all available evidence suggests Grant had abstained from alcohol ... through sheer willpower and perseverance — his stock in trade.”

But overall the book is worth its weight in bold evidence of Grant’s loyalty to a Union in which men are created equal. On the other side, Gen. Robert E. Lee’s action belies “the notion that Lee fought simply from loyalty” to Virginia and “betokens a more militant attachment to Confederate ideology.”

Under Chernow’s command, Grant is a leader with a conscience and “a soldier in his marrow.” In Mexico in 1846 he is “tranquil in warfare, as if temporarily anesthetized, preternaturally cool under fire” in his first fight. With a “visceral instinct for fighting” he becomes “a master of the psychology of war.”

Moving from general to president, he realizes “one big thing: His main mission was to settle unfinished business from the war by preserving the Union and safeguarding the freed slaves.”

Neither task is easy. There is a “broadly based retreat from many of the ideals that had motivated the northern war effort” including terrorism against black people, and the novice president who is “accustomed to the automatic obedience of huge armies” must “brook the vagaries of petty politics and wayward personalities.”

Grant perseveres despite a constant cigar (“an ultimately fatal addiction”) and lifelong financial losses. He is gullible, a man who “could recognize evil in his enemies but not in those who posed as his friends.” The Brooklyn Bridge was finished two years before Grant died in 1885, and you wonder if anybody tried to sucker him into buying it.

His friends — not posers — include Frederick Douglass, Andrew Carnegie, who sends 63 roses when Grant reaches 63, and Mark Twain, who publishes the memoirs that preserve the Grant family’s fiscal status and the president’s reputation for brilliance.

Besides cementing Grant’s stature, the book is a reminder that Chernow’s “Alexander Hamilton” is the inspiration for Broadway’s box-office phenomenon, the musical “Hamilton.” Imagine “Make the U.S. Grant Again” on a marquee.

Our Year of War: Two Brothers, Vietnam, and a Nation Divided by Daniel P. Bolger, 336 pages, Da Capo, $28.

The Hagel brothers — the older, Chuck, later is a senator and then a secretary of defense — are the subjects but the war is collectively America’s, yours and mine and “ours,” in Vietnam or back home.

The book is an attempt “to explain the significance of the tumultuous events of the Vietnam War and 1960s America.” The author of “Why We Lost” in Afghanistan (he was there) fulfills his mission.

The two soldiers are Tom and Chuck, serving and suffering in the same platoon. One is for the war, one is against it, and both fight in it.

In one three-week period, the sons and grandsons of veterans of two world wars share four Purple Hearts. Their tour amounts to “a lifetime of combat: Tet, patrols, ambushes, roadrunner ops, calling in artillery, arranging medevacs, twice wounded.”

You could quibble occasionally. Does a reader need six pages about George Wallace’s presidential campaign? And picture this: At a press conference featuring Gen. William Westmoreland, camera bulbs are “brilliantly white,” “dazzling,” “intense”, “luminous,” “intense” again, and full of “vibrant luminosity.”

However, most of the time the siblings’ story, a part of the American fabric that Bolger weaves deftly, sucks you in. Savor this, for example:

“So there it was. A superpower at war, a half million men in country, the famous 9th Infantry Division charging hither and yon applying ... patented ‘excruciating pressure’ to the enemy, and it came to this.

“Forty-odd smoked, scared infantrymen counted on a 19-year-old and a 20-year-old — both bloodied up, neither in the army an entire year yet — to get them to safety. The U.S. Army put itself in this mess.”

That is the assessment of a retired Army general whose experience — including Iraq — adds meaningful punch. Bolger’s is “an infantryman’s account of two infantry sergeants,” and “there’s a broader story told because there’s always more to war than fighting.”

The Pentagon’s Wars: The Military’s Undeclared War Against America’s Presidents by Mark Perry, Basic, 368 pages, $30.

Don’t be misled by the subtitle and begin to feel sorry for commanders in chief. They know how to fight, also.

Besides, most of the squabbles in this “narrative account of the politics of war” are among friends — or so they think — in the Defense Department. Nobody at the Pentagon needs to cross the Potomac to have a spat.

The historian’s 1989 “Four Stars” looks at senior commanders and their civilian counterparts from World War II through the Cold War, and this book takes readers through the end of Obama’s administration.

In one corner? The Joint Chiefs of Staff, which must count the beans even during wartime. In 2006, Iraq strategy “fed into JCS worries that the war was cutting into military readiness. Building and maintaining the military was in the JCS’ interest; fighting a war undermined that.”

The paragraph’s citation credits a “senior Joint Chief officer.” Another cites “a senior Pentagon official,” and another a “senior U.S. Marine Corps officer.” If only those footnote soldiers would give their names, especially the one who says then-Marine Corps Gen. Jim Mattis feels “he needed to parade his masculinity.”

Meow. Some readers will consider such a catfight as blasphemy.

Whatever the sources — many are on the record — the highly readable book is a DoD version of TV’s “Dynasty,” so full of dirt you want to drain the pentagonal swamp:

- “Donald Rumsfeld wasn’t the smartest guy in the room, he just thought he was.”

- Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz’s allies attack Gen. Eric Shinseki’s Iraq testimony. “Shinseki doesn’t know what he’s talking about, they said.”

- When CIA head George Tenet hears that Rumsfeld named L. Paul Bremer as chief envoy in Baghdad he turns to an assistant and says, “Who the f--- is Jerry Bremer?”

The examples are fun — until you remember that the stakes are serious.

In 28 years “no single senior military officer of any service has ever told a president ‘no’ — or even ‘yes sir, but.’ Except for one: Colin Powell told Bill Clinton ‘no’ — and that was on the issue of gays in the military, hardly as momentous as sending men and women to their deaths.” (More than a few readers might tell Perry that the two points are not exclusive.)

Code Girls: The Untold Story of the American Women Code Breakers of World War II by Liza Mundy, Hachette, 432 pages, $28.

Women who helped bring victory achieve visibility, at last, in this history.

Everybody knows about Rosie the Riveter, says the author, a former Washington Post reporter. But “far less well known is that more than 10,000 women traveled to Washington, D.C., to lend their minds and their hard-won educations to the war effort” — all at a time when “there was really only one job consistently available” to an educated female: schoolteacher.

And being recruited to work secretly for 12 hours a day was not a feather on a woman’s hat. “That women were considered better suited for code-breaking work ... wasn’t a compliment.

“To the contrary. What this meant was that women were considered better equipped for boring work that required close attention to detail rather than leaps of genius.”

Yet some achieve recognition at the Army and Navy’s separate decoding shops, competitive “to a degree that would have been comic if it weren’t taking place in the middle of a war.” By 1945, 7,000 of the Army’s 8,000 code breakers are female, as are 4,000 of the Navy’s 5,000 in Washington. Their interpreting of messages from Germany and Japan makes a difference from Normandy to Midway Island.

“As the Japanese coped with their changing (Pacific) island situation, the ex-schoolteachers had to cope with Japanese cryptanalytic changes” to the tune of 30,000 messages each month — a thousand a day — in 1944. The author maps out military coding in minutia that can be tedious, but she compensates by wisely relying mostly on the personal stories of the “girls.”

At 96, Dot Braden is finally able to tell her family what she did during the war. Ann Caracristi, the “peerless secret-keeper in every way” who becomes a deputy director at the National Security Agency, is buried beside her “longtime companion” — who also came to the capital in 1943.

Withdrawal: Reassessing America’s Final Years in Vietnam by Gregory A. Daddis, Oxford, 320 pages, $30.

The history professor, author and West Point graduate challenges some of “the more popular preconceptions held on the American experience in Vietnam,” what he calls “a miscarried” war, a “costly military stalemate.” His is a worthwhile “new perspective for those looking back to history for wisdom in managing current and future conflicts.”

The Gulf War and Operation Iraqi Freedom veteran resists blatant comparisons of those two wars with Vietnam — although he suggests that in Iraq, Army Gen. George Casey “could conveniently play the role of William Westmoreland with David Petraeus performing as the new [Creighton] Abrams.”

Abrams has top billing, and his “signal accomplishment was to alter, if only temporarily and reluctantly, the U.S. military culture from one captivated by visions of traditional battlefield ‘victory’ to one accepting the obligations of a political alternative in Vietnam.”

Everybody’s vision is blurred. “In the eyes of many American soldiers, the South Vietnamese acted more like dim understudies than true partners.” And the South fails to supply “a political education that might have committed its soldiers ideologically to the Saigon government.”

By 1969, President Nixon “envisioned Vietnamization as a policy of withdrawal rather than a strategy for victory. In the end, “no amount of American military muscle ... could resolve the fundamental issue of whether South Vietnam was a viable nation capable of effective governance.”

Grateful Nation: Student Veterans and the Rise of the Military-Friendly Campus by Ellen Moore, Duke, 280 pages, $26.

Born “on a U.S. military base to an Army captain father and a pacifist mother,” the author dedicates her study to veterans, including “those committed to ending war.”

Her dissertation is ethnologic, exploring how civilians and veterans interact on campus. She wants to “help people differentiate between support for veterans and support for the wars in which they fought.”

After three years’ immersion primarily at unidentified California schools — an “elite” university and a community college — and interviews with at least 50 student veterans, what does she learn?

- “Academic challenges are caused not by collegiate hostility toward the military but by multiple factors, including disjunctions between veterans’ military training and academic demands, and psychological trauma.” And many enroll “to make sense out of their psychologically disjointed experiences of war” … and to get a degree.

- Culture suggests veterans “should serve as venerated representatives of the current wars,” and those assumptions “form part of a growing militarized sense on campuses.”

- Programs “based on an ideology of military superiority” can further distance veterans from civilian classmates and can be “a forum for military valorization.”

- “When ‘veteran friendly’ automatically comes to mean ‘military friendly,’ critical examination of the wars will be suppressed, and some veterans will be excluded” from criticizing wars they fought.

- “Reflexive, mandated gratitude” — offering thanks for a veteran’s service — “absolves U.S. civilians from engaging in public debates about wars carried out on their behalf.”

8 Seconds of Courage: A Soldier’s Story from Immigrant to the Medal of Honor by Flo Groberg and Tom Sileo, Simon & Schuster, 208 pages, $25.

Eight seconds refers not to how long it takes to read the memoir — although it is an easy task and the third effort by co-author Sileo, who brought similar, stick-to-what-happened, serviceable approaches to “Brothers Forever” and “Fire in My Eyes.”

Instead, the measure is the time Groberg takes — on his first day as a captain — to confront a suicide bomber. His effort saves other soldiers’ lives, although the Medal of Honor recipient wishes he had done more, and his last day in Afghanistan is a prelude to recovery that includes 32 surgeries.

The book illustrates how a French immigrant (his mother is Algerian) is full of American blood, and how a guy — whose first sentence admits his thinking about quitting Ranger School during the mountain phase — ends up doing the right thing.

An American Family: A Memoir of Hope and Sacrifice by Khizr Khan, Random House, 288 pages, $27.

Showing a pocket-sized copy of the Constitution was a Pakistan-born lawyer’s last-minute amendment to his two-minute speech at last year’s Democratic National Convention.

The moment put Khan, the son of a farmer, and his wife, a descendant of Afghanistan royalty, on the political map for his rhetorically asking GOP candidate Donald Trump whether he had read the Constitution.

The book is as plain and simple as Khan’s address and chronicles his leaving Pakistan for Dubai and eventually the U.S. To save money so he can send for family, Khan eats bread from a dumpster and sleeps in parks. But “I never felt that we were giving anything up.” Instead “I focused on what we were gaining” as citizens.

However, his Army captain son Humayun’s death in Iraq brings an “immutable and eternal void.” Yet “we can only be grateful for the 27 years we had with him.”

The book is more about dad than son, but the soldier’s selflessness, even as a teenager, is touching — and represents American ideals worth emulating.

Proceeds from sales of the book go to the Capt. Humayun S. Khan Memorial Scholarship at the University of Virginia.

Craig & Fred: A Marine, A Stray Dog, and How They Rescued Each Other by Craig Grossi, Morrow, 288 pages, $26.

A Marine’s best friend, or close to it, is his dog. In this memoir, a sergeant and a stray befriend each other in Afghanistan.

The feel-good story, told with an acknowledged co-author (Kelly Shetron), alternates between deployment and a cross-country trip with a Marine buddy and, of course, Fred — the word Grossi mistakenly hears when another Marine refers to the mutt as “friend.”

Having a pet is outside regulations, but Fred provides an “escape from the combat zone we were in,” and he finds fraternity. Shipping a dog home is also a no-no — “I knew it wasn’t right” — but supportive shippers and forged signatures expedite the egress.

Stateside, Fred’s behavior shows the wounded Grossi that “it’s not what happens to you that matters, it’s about how you make meaning out of those experiences,” and that’s the tale of this dog.

The experience is also available in a young reader’s edition ($17).

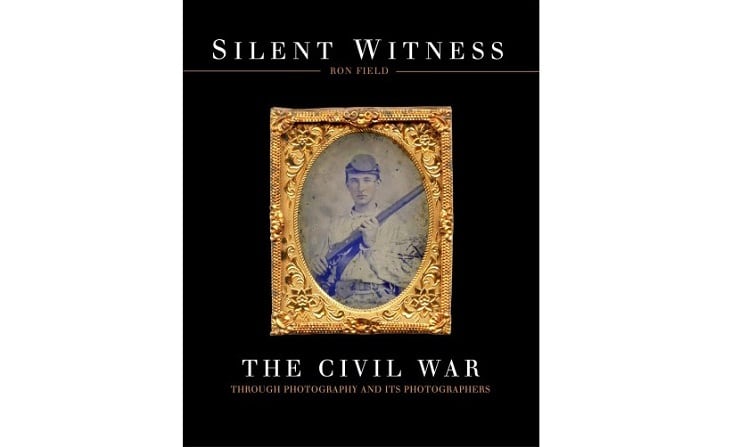

Silent Witness: The Civil Through Photography and Its Photographers by Ron Field, Osprey, 328 pages, $35.

Handsomely reproduced portraits in ornate frames dominate the selection by a Military Images magazine editor who taps his personal archive for photographs that make the book stand out.

The focus is on the men behind the camera, but the impact is in the faces of the mostly young soldiers who are most of the subjects. Except for references to the Smithsonian “Institute,” the coffee-table book is presented with care and class.

The Gun Club: USS Duncan at Cape Esperance by Robert Fowler, Winthrop & Fish, 366 pages, $16.

He never met his father, Navy Lt. Robert L. Fowler, a newlywed Harvard rower who died when torpedoes sank the destroyer Duncan during a 39-minute battle with the Japanese navy off the Solomon Islands.

But the author’s use of ships’ logs and his interviews with survivors produce an hour-by-hour, just-the-details report of what happens to the sailors aboard the destroyer. Sadly, in 1942 the Navy’s lack of recent fighting experience means its “ships, commanders and tactics were all found wanting.”

The executive officer treats his men like a ship of fools, and the captain’s after-action report is “a masterpiece of obfuscation.” In 1991, the author writes, “quite a few of the men told me that when they read Herman Wouk’s novel ‘The Caine Mutiny’ they thought it was about the Duncan.”

Long Way Out: A Young Woman’s Journey of Self-Discovery and How She Survived the Navy’s Modern Cruelty at Sea Scandal by Nicole Waybright with Jim Bastian, SpeakPeace, 552 pages, $18.

Internal bother is strong to seethe in this fastidious memoir about a square peg trying to fit into a porthole. In third person and with names changed, “Brenda” self-analyzes the psychology behind her not knowing “how to act” where “every move she made onboard felt foreign.”

When the destroyer Curtis Wilbur gets a new executive officer called Heather Astrid Gates — the acronym “HAG” — Brenda’s self-predicament gets no ballast from her bombastic boss (whose real name is thinly veiled).

Finally the lieutenant junior grade’s true calling comes to the surface when a shipmate offers her a belated but astute assessment: “I think that you’re a very bright young woman who seems extraordinarily unhappy aboard a ship and in the military.”

Duh.

Racing Back to Vietnam: A Journey in War and Peace by John Pendergrass, Hatherleigh, 256 pages, $15.

An Air Force flight surgeon occupies “the backseat of a workhorse fighter of the Vietnam War: the F-4 Phantom” and returns on a bicycle seat in a triathlon 44 years later.

He finds that “relatively few of today’s Vietnamese can actually remember the Americans” but “everyone has a family story about the war.” His travelogue follows that model with impressions that are more personal than profound.

Warrior Pups: True Stories of America’s K9 Heroes by Jeff Kamen with Leslie Stone-Kamen, Lyons, 184 pages, $14.

An airman is “a gentle soul with an easy smile and enormous love,” and that description typifies the rest of the happy humans and the language in this look-and-read book about people who work with Belgian Malinois military working dogs.

The canines have names, but people have only “real first names and last initials” because “a famed American anti-terrorist” advises the author to protect identities. Nevertheless, their faces are recognizable in dull photographs that unintentionally show why cat videos rule the Internet.

NOTED, NOT REVIEWED

- Endurance by Scott Kelly, Knopf, 400 pages, $30. The retired astronaut and Navy captain (just like his twin brother) presents the right stuff in his life, which includes a famous 340-day stint in space.

- My Lai: Vietnam, 1968, and the Descent into Darkness by Howard Jones, Oxford, 504 pages, $35. A history The New York Times Book Review says “is likely to become the standard reference work” about the killing of at least 300 villagers.

- The Fear and the Freedom: How the Second World War Changed Us by Keith Lowe, St. Martin’s, 576 pages, $30. The British historian’s take on how the conflict changed everything including “the way we think about ourselves.”

- Arthur Vandenberg: The Man in the Middle of the American Century by Hendrik Meijer, Chicago, 448 pages, $35. The uncle of General Hoyt S. Vandenberg (for whom the Air Force base is named) is a centrist Republican, and the biography shows how the senator builds bipartisan consensus ― now a rare concept.

- The West Point History of the American Revolution by the U.S. Military Academy, Simon & Schuster, $55. Full of illustrations including maps, this is the fourth coffee-table book in a pleasantly designed series that includes the Civil and World wars.

- The Great Halifax Explosion: A World War I Story of Treachery, Tragedy, and Extraordinary Heroism by John U. Bacon, William Morrow, 432 pages, $30. As the world fights in Europe, a U.S. munitions ship explodes in a Nova Scotia bay and kills 2,000.

- Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World by Laura Spinney, PublicAffairs, 352 pages, $28. As if war were not devastating enough, a pandemic infects “a third of the people on Earth” and kills at least 50 million.

- How We Won and Lost the War in Afghanistan: Two Years in the Pashtun Homeland by Douglas Grindle, Potomac, 280 pages, $30. The former war correspondent and field worker for the U.S. Agency for International Development describes how “our little group of Afghans, Americans, and Canadians tried to keep out the Taliban and bring hope to the poor farm families.”

- The Return on Leadership: A Three Step Plan to Navigate Change and Unlock Hidden Growth by D. L. Brouwer, FastPencil, 265 pages, $21. The former Navy flight officer offers examples to show why “growth isn’t just capital-intensive or labor intensive. It’s leader-intensive.”

- Soldier & Spouse and Their Traveling House by Matthew Alan House, Gatekeeper, 180 pages, $17. The newlywed Army officer wife use off-duty weekends to play tourist and to share their adventures in this travelogue.

- The Sniper Mind: Eliminate Fear, Deal with Uncertainty, and Make Better Decisions by David Amerland, St. Martin’s, 416 pages, $28. The British journalist and speaker who interviewed “over 100 snipers” offers ways to apply their “complex fusion” of skills into your own “mental toughness.”