What happens when the crew of an M2 Bradley fighting vehicle finds itself having to engage enemy combatants at close quarters at the sides and rear?

The Bradley’s main weapons — namely its 25 mm chain gun and a coaxial machine gun — would be pretty useless, or at least that’s what the Army hypothesized some 40-odd years ago during the Mechanized Infantry Combat Vehicle program of the 1970s that would eventually spawn the M2 in the following decade.

As a result, the Army set its sights on developing an automatic weapon that could be fired through ports on the MICV’s final product in order to ward away and mow down would-be swarmers, especially in urban scenarios.

In short order, the Army’s Rock Island Arsenal began evaluating potential prototypes including the M3 Grease Gun of Second World War heritage and fame, only to settle on a derivative of the M16 — at the time, the military’s still relatively new standard service weapon.

Colt, then the only producer of the military’s M16s, was given the task of modifying the M16 to suit the firing port weapon’s objectives, namely something that could be maneuvered and wielded effectively in tight/confined spaces, and a gun that could unleash unholy hell on any enemy fighter who dared to stray too close to the armored vehicles.

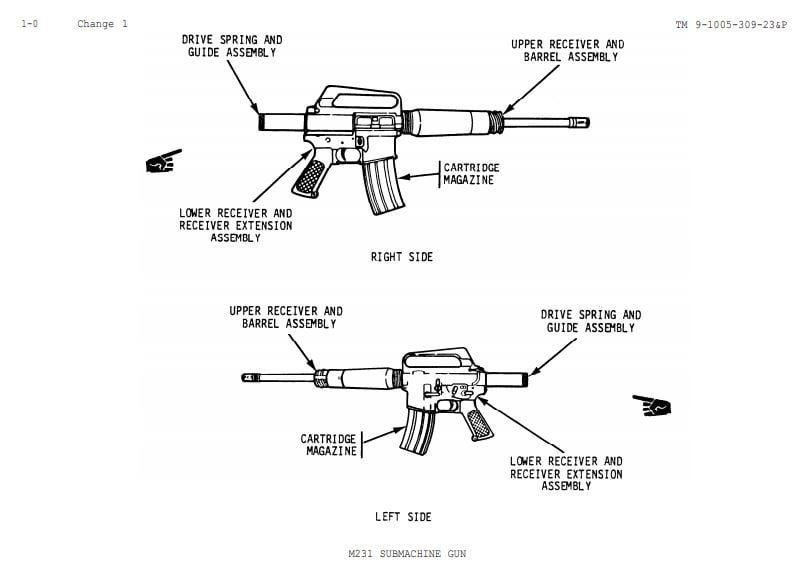

Firing from an open bolt, and featuring a heavier-than-normal bolt carrier group as well as a shortened barrel, the result of Colt’s modification regime was dubbed the XM231, later officially designated the “SUBMACHINE GUN, 5.56-MM: PORT, FIRING, M231” when adopted by the Army.

Like the M16, it was chambered for the 5.56x45mm NATO cartridge. Unlike the M16, the M231 could only shoot automatic. Designed to put lead downrange at over 1200 rounds per minute when fired cyclic, the M231 was indeed a vicious animal of a rifle.

Built with a shortened handguard with an external thread, it was meant to be screwed into place within firing ports on the Bradley.

Interestingly enough, M231s were never meant to be aimed through any sighting apparatus on the gun itself. Instead, end-users would load magazines filled with tracers and correct their fire by watching the direction of their bullets through vision blocks, marching in their rounds on target.

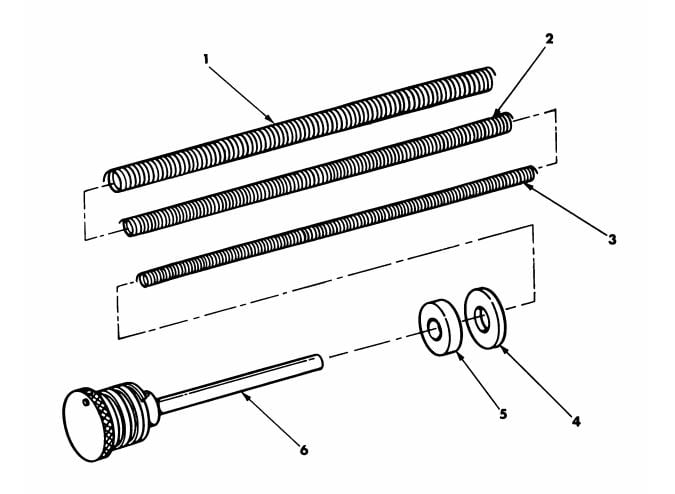

The gun’s buffer tube (in a design that was fairly novel for the times) used three springs, all placed within each other like Russian nesting dolls, to reduce the rate of fire to something slightly more tolerable. Nevertheless, the M231 could eat through a fully-loaded magazine in seconds if the shooter wasn’t disciplined with his trigger finger.

Initial M231 prototypes came with a wire stock, though that was done away with seemingly to prevent soldiers from grabbing the weapon during dismounted patrols, instead of their M16s. The Army’s final product also used a longer barrel (15.6 inches) than Colt’s XM231 prototype.

The need for the rifle gradually died down when the service began closing up the firing ports on its Bradleys, leaving just the rear ports for close-in defense.

While the Army procured over 27,000 M231s to support over 6,700 Bradleys fielded from 1981 to the present day, the gun has mostly faded into obscurity though they have made fleeting appearances in various combat zones during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Despite this, armories have been known to keep the weapon in stock for Bradley crews, albeit with extremely limited usage.

Ian D’Costa is a correspondent with Gear Scout whose work has been featured with We Are The Mighty, The Aviationist, and Business Insider. An avid outdoorsman, Ian is also a guns and gear enthusiast.