Operating at night and virtually invisible to radar, the F-117 Nighthawk racked up a near-perfect combat record.

After crossing the Serbian border at 18,000 feet, U.S. Air Force Lieutenant Colonel William “Brad” O’Connor’s F-117 Nighthawk Initiated a computer-programmed hard turn west of the night lights of Belgrade, toward his primary target, the Baric munitions plant on the Sava River. He completed his stealth check by flipping the “inert” switch to pressurize the empty volume in his fuel tanks with nonflammable gas, to help suppress fire if he was hit.

Just then the excited voice of an F-16 pilot flying cover burst over the net: “Heavy triple A west of the city at medium altitude!”

Streams of silvery anti-aircraft rounds swung back and forth like spray from a garden hose to the right of O’Connor’s flight path. The heavier stuff, 57mm, was a deep reddish color with a tinge of yellow. O’Connor pitied the poor schmucks over in that zone until he suddenly realized his next programmed turn took him directly into the thick of it.

A minute later, his bull’s-eye display provided even more chilling news. “I’m the only one here,” he realized. “They’re shooting at me!”

The Nighthawk was the world’s most invisible attack bomber; radar was nearly blind to it. So what the hell was going on? Some guy down there with a $200 pair of night-vision goggles?

It was April 17, 1999 — almost three weeks into NATO’s air campaign against Slobodan Milošević’s Serbs in Kosovo, and O’Connor’s sixth sortie in a war that was not a “war.” The White House under President Bill Clinton specifically ordered all agencies to avoid using the words “war” or “combat.” Action was to be referred to as “strikes.”

The latest round of carnage in the former Republic of Yugoslavia involved the ethnically Serbian part of Kosovo under Milošević against the ethnic Albanians and their rebel KLA, or Kosovo Liberation Army. Armed violence broke out in early 1998. Massacres and terror attacks either killed or displaced nearly a million Kosovo Albanians.

On March 23, 1999, NATO Secretary General Javier Solana directed the supreme allied commander Europe, U.S. General Wesley Clark, to initiate air operations against the Federal Republic of Kosovo, with the objective of rendering Milošević incapable of continuing his persecution of ethnic Albanians, who were legally Kosovars in international eyes. Led by the U.S., NATO began bombing key targets the next night with 1,000 aircraft operating out of bases in Italy and Germany and from the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt in the Adriatic Sea. It was to be the first U.S. conflict fought entirely from the air and the largest sustained action since Vietnam, with more than 38,000 combat sorties in 78 days from March 24 to June 11. Lockheed’s F-117 Nighthawk played a major role in the campaign.

Long before O’Connor ever set eyes on the top-secret Nighthawk, he and other Air Force pilots training out of air bases at Nellis, Holloman and Tonopah next door to Area 51 knew something flew at night out there over the New Mexico and Nevada deserts. The area formed the epicenter for secret post–World War II experiments in warplanes and spacecraft.

V-2 rocket tests in the late 1940s carrying chimpanzees wearing little spacesuits went wildly astray on occasion and crashed. Anthropomorphic dummies dressed in experimental spacesuits were regularly pitched out of a variety of airplanes and balloons. A manned extreme-altitude balloon crashed near Roswell. In 1981, when the Nighthawk made its maiden flight, residents in the dark areas outside the glow of cities revived the old UFO rumors by whispering of shadows and mysterious lights in the sky.

Flying the F-117 remained top secret for more than a decade. Like a vampire, it came out only at night so it wouldn’t be seen. Flights were canceled if the moon was too bright. Pilots were forbidden to tell even their families what they were doing.

Early in 1998, the assignments officer at “The Porch” personnel center advised Lt. Col. O’Connor of his next assignment: “Congratulations. You got the Black Jet you asked for. Learn to be comfortable with the night.”

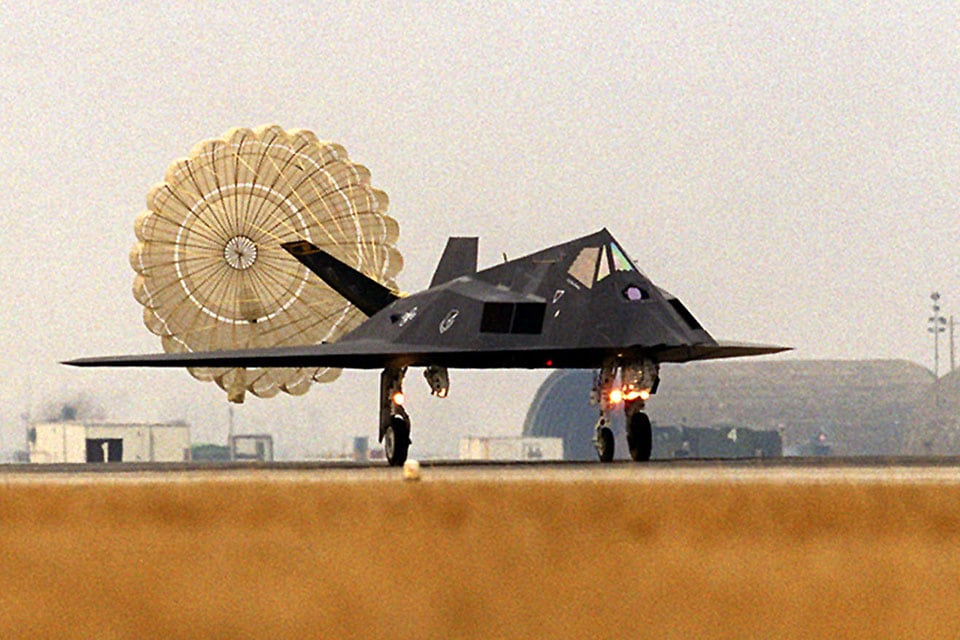

Seeing the bird for the first time, O’Connor walked around it with an awestruck expression. His first impression was that a demented diamond cutter must have carved it out of a very large chunk of coal. It was matte black, hulking, low and uneasy on the ground. Not a single curve on the entire fuselage to make it aerodynamically normal. Nothing but black facets. Something out of a sci-fi movie.

Although commonly referred to as a “stealth fighter,” the plane was strictly intended for ground attack and performed superbly against Iraqi forces during the 1991 Gulf War. It flew 1,300 sorties and scored direct hits on 1,600 high-value targets without losing a single aircraft. In fact, since the stealthy F-117 operated at night, no enemy could claim to have actually seen one. Leaflet drops on Iraqi forces displayed it in an eerie stylized version destroying ground targets with the warning below: “Escape now and save yourselves.”

Seventeen pilots successfully completed Nighthawk training in 1998 to become members of the F-117 fraternity. Each was assigned a “bandit number.” O’Connor’s was 545, which meant he was the 395th pilot in the series to fly the jet, since bandit numbering began at 150. More NFL players have suited up on any given Sunday than the total number of pilots ever privileged to fly the Nighthawk.

O’Connor was assigned to the 8th Fighter Squadron, which traced its lineage back to WWII as the 49th Group’s famed “Black Sheep.” Within the year he would be flying his first strikes over Kosovo — his baptism of fire.

The closest O’Connor had come to combat previously was being assigned to Operation Southern Watch in 1996, flying the EF-111 out of Saudi Arabia to enforce the no-fly zone against Saddam Hussein. Before that, in 1993, two years after the Gulf War, he pulled a tour in Egypt training Egyptian pilots to fly F-16s.

The project to develop a combat aircraft with a low radar signature that led to the birth of the F-117 began in 1974 when the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) launched Project Harvey, so-named after the invisible white rabbit from the play and movie. Lockheed Aircraft’s “Skunk Works,” the official alias for the department responsible for highly secret advanced development projects, soon took up the mission.

Skunk Works had arrived on the aircraft scene in 1943 and soon became famous for building small fleets of extremely advanced warplanes such as the P-80, America’s first operational jet fighter; the F-104 Starfighter, the only fighter of the period capable of exceeding Mach 2; the high-flying U-2 spy plane of the Cold War; and the SR-71 Blackbird Mach 3 reconnaissance plane. Legendary Lockheed aircraft designer Kelly Johnson suggested the new radar-invisible stealth project should be patterned to resemble a flying saucer, which would most assuredly have contributed to rumors of alien landings if it were spotted test-flying in Area 51 airspace.

Johnson retired before the project was completed, and engineer Ben Rich succeeded him as director of Skunk Works. Along with engineers Denys Overholser and Bill Shroeder, he stumbled upon a paper published by Pyotr Ufimtsev, the Soviet Union’s chief scientist at the Moscow Institute of Radio Engineering. Titled “Method of Edge Waves in the Physical Theory of Diffraction,” the paper discussed optical scattering of electromagnetic waves bouncing off variously shaped objects. To Overholser it suggested that individual plates could be offset and reoriented to deflect radar waves away from an aircraft, thus rendering it “invisible.”

Using a process known as “faceting,” Rich’s team built a single-seat jet with no curved surfaces whatsoever. It emerged with hundreds of individual flat triangular and rectangular plates. The team further reduced the F-117’s infrared signature with a slit-shaped tailpipe to minimize exhaust cross-sectional volume and maximize rapid mixing of hot exhaust with cool ambient air. Afterburners were eliminated because of the hot exhaust they created. The Nighthawk would be subsonic since breaking the sound barrier produced a sonic boom and heated up the aircraft skin, increasing its IR signature.

The oddly constructed “Hopeless Diamond” had neither the speed nor maneuverability of a fighter — which it was never intended to be. It was an attack bomber that emitted virtually no radar signature with landing gear retracted and bomb bay doors closed.

“No aircraft…that ugly could possibly be any good,” Kelly Johnson commented, perhaps still dismayed because it didn’t look more like a flying saucer.

Many other inglorious names were subsequently attached to the airplane: Roach, Wobbly Goblin, Stinkbug. Pilots simply called it the Black Jet.

Now over Kosovo, O’Connor flew one of only 64 Black Jets ever manufactured (including five test aircraft), as triple-A lashed across the night sky. He recalled Winston Churchill’s comment about there being “nothing more exhilarating than to be shot at without result.”

The F-117 could be preprogrammed to virtually fly itself onto a target. The stealth jet was inherently unstable, and required constant corrections from a fly-by-wire system to maintain controlled flight.

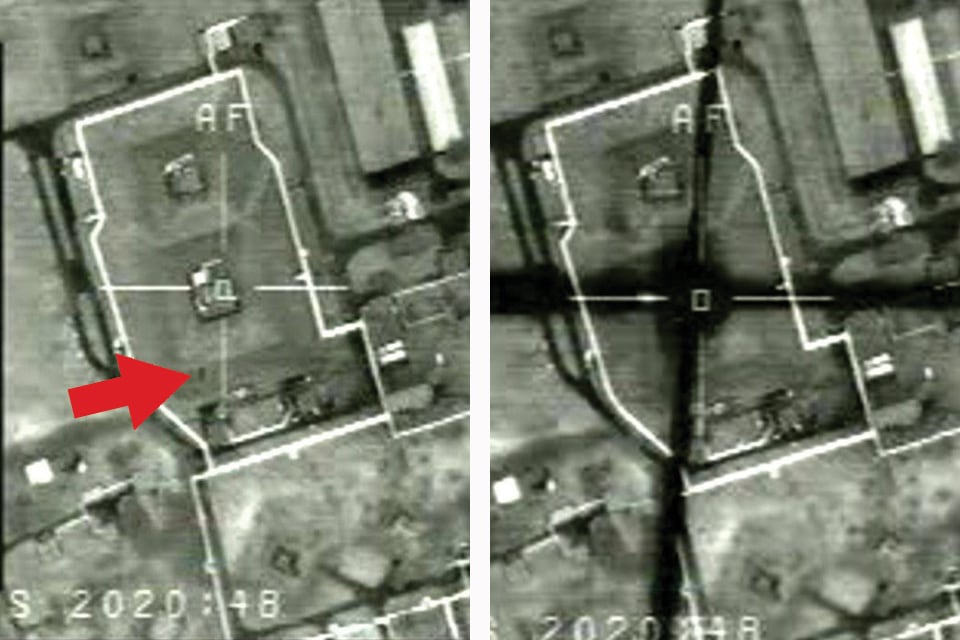

About three minutes out, O’Connor’s aircraft made a preprogrammed climb that took him above all the AAA except the 57mm shells. At two minutes out, he focused on his target display showing the Baric munitions plant and ignored the pyrotechnics outside the cockpit. The flip of a switch placed the cursor on a mixing tower at the plant. Now concentrating on his bombing run, he tuned out urgent radio chatter in the background about surface-to-air missile activity and ignored the fact that he was well within SAM range.

Aloud, he talked himself through the procedure. “Level attack, Record, Ready, Narrow, Cued, MPT [manual point tracking].”

He felt the bomb bay doors open and the 2,000-pound laser-guided bomb drop. Ten seconds later, his laser “auto-fire” symbol appeared. He counted down in unison with the computer the seconds until impact.

A tiny puff appeared on his target display, followed by shock waves that showed a direct hit. His Nighthawk then made a preprogrammed hard turn east toward Belgrade and his secondary target, the Novi Sad refinery northwest of the city. “What a hell of a way to make a living,” O’Connor muttered to himself.

Later he learned from pilots in adjacent zones that a barrage of AAA had followed him through the turn and that several SAMs had been shot toward him, enemy radar having apparently glimpsed him when his bomb bay opened. Concentrating on his display screens coupled with a severely limited view outside the cockpit had kept him blissfully unaware of threats coming his way, but now he felt an adrenaline rush.

Churchill was right.

Almost all the strategic military targets in Kosovo were destroyed by the third day of the campaign. Milošević’s Serbs still refused to capitulate and continued assaulting the ethnic Albanians. NATO strikes turned to strategic targets such as bridges, government facilities, factories and industrial plants.

Two Americans died during the air campaign. Army Chief Warrant Officers David Gibbs and Kevin Reichert were killed when a technical malfunction caused their AH-64 helicopter to crash and explode during a night training mission over Albania.

The only Nighthawk ever lost in battle went down on March 27, 1999, as the result of a SAM fired from about eight miles away. Nighthawks were generally only visible to radar when their bomb bay doors opened to cast radar signatures. Lieutenant Colonel Dale Zelko bailed out of the stricken aircraft and was recovered by a U.S. Air Force rescue team.

The air campaign ended on June 11, 1999, with the Kumanova Treaty. Milošević was eventually arrested by his own people and charged with crimes against humanity. He died in prison before his trial produced a verdict.

The F-117 fought once again when the long war against Iraq began in March 2003. The first U.S. warplane constructed entirely on top-secret stealth technology remained the most invisible and most deadly aircraft in the world until the Air Force retired it on April 22, 2008, replacing it with the F-22 Raptor and soon the F-35.

Lieutenant Colonel Brad O’Connor retired from active duty in 2007. He went from piloting the Black Jet to flying a C-47 Skytrain as a volunteer for the WWII Airborne Demonstration Team in Frederick, Okla. The plane he now flies, Boogie Baby, previously delivered paratroopers onto drop zones in Normandy on D-Day in 1944.

Charles W. Sasser spent 29 years in active and reserve service with the U.S. Navy and Army Special Forces before retiring. He is the author of more than 60 books and some 3,500 magazine articles and short stories. Additional reading: Stealth Fighter: A Year in the Life of an F-117 Pilot, by Lt. Col. William B. O’Connor (USAF, ret.).

This article originally appeared in the July 2016 issue of Aviation History Magazine, a sister publication of Military Times. For more information on Aviation History Magazine and all of the HistoryNet publications, visit historynet.com.

Read more from HistoryNet:

- What we learned: from the Tet Offensive

- Did Gen. Pershing threaten to execute cowards?

- The other Cactus Air Force