A purposeless existence, an enlistment, war, post-traumatic stress disorder, opioid addiction, crime, redemption.

The sequential, and perpetually spiraling, story of “Cherry,” starring Tom Holland (“Spider-Man: Homecoming”), is everything one might expect from a character whose addiction evolves to supersede anything that once held value. A marriage shaken to its core, parents and family alienated, death, financial ruin, self-sabotage.

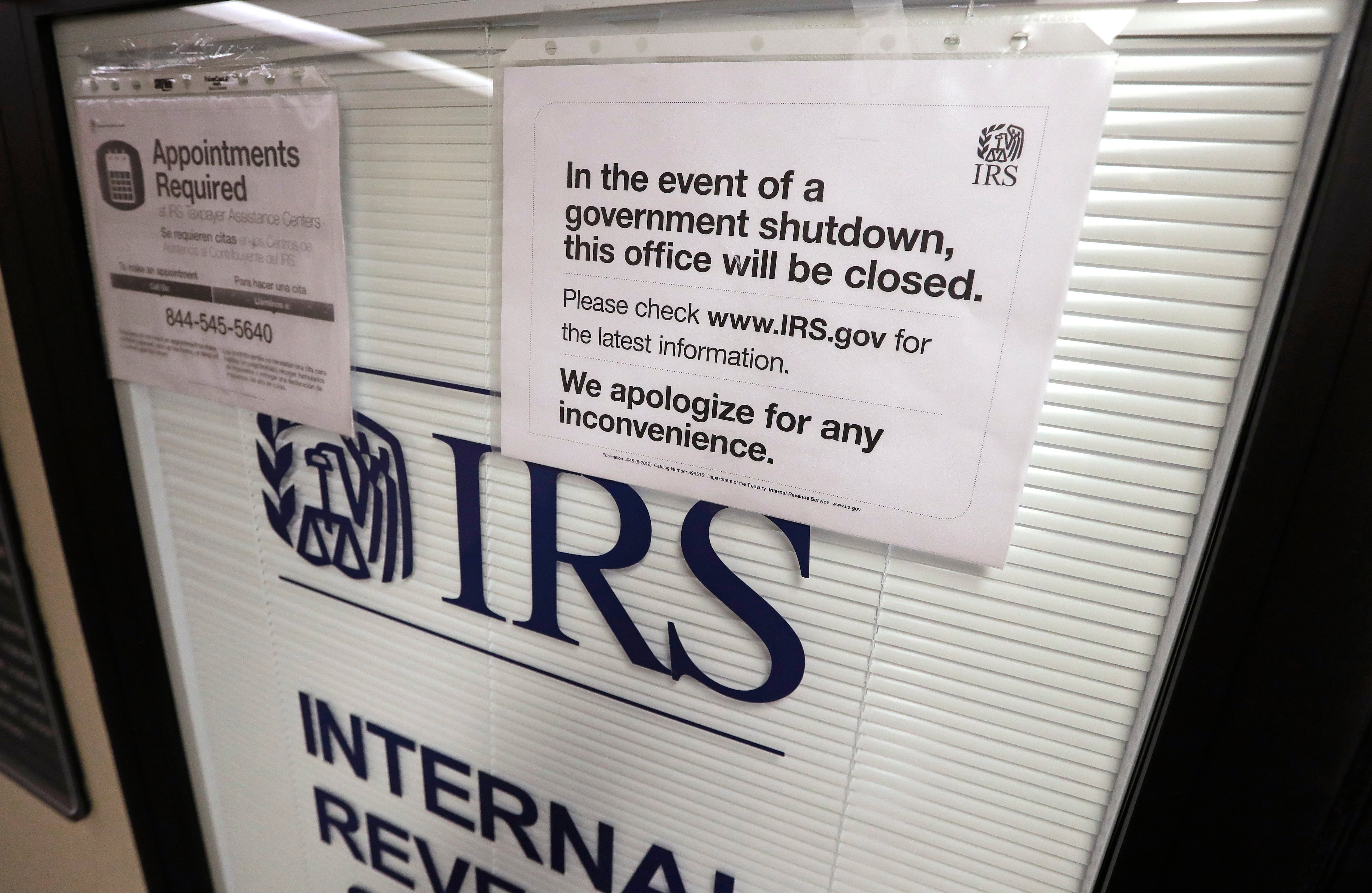

Holland’s unnamed lead is an interpretation of the semi-autobiographical novel by Nico Walker, a former U.S. Army medic with a post-military service heroin addiction that eventually dovetailed into a series of bank robberies from 2010-11 across Cleveland that were meant to fund his habit.

Walker, who was sentenced to 11 years in prison after his arrest, wrote his best-selling book of the same name while behind bars. Directors Joe and Anthony Russo acquired the rights to the work in 2018, right on the heels of spearheading Marvel smash hits like “Avengers: Infinity War” and “Endgame.”

The Russo’s finished version is a chapter-by-chapter, increasingly detrimental journey meant to represent far more than the plight of its title character or author on whose work it’s loosely based. Its military-centric chapters, meanwhile, are smattered with detail uniquely appreciated by those with military service.

“I was too easy,” Holland regretfully narrates during one scene while sitting opposite an Army recruiter whose name tag simply reads “WHOMEVER.”

“He knew he had me, so by the next day I was sworn in.”

And while naked duck walks, interminable vaccination lines, and porta john-based degeneracy capture lighter elements of military service seldom featured on the big screen, it is Holland’s disillusionment with war and his deployment to Iraq’s “Triangle of Death” that will resonate with many veterans of the global war on terrorism.

“I really want to get the fuck out of here,” Holland narrates during a homecoming celebration in a school gymnasium, families waving flags and holding “Welcome Home” signs.

“My one true accomplishment was not dying. I didn’t really have anything to do with that.”

In a conversation with Military Times, director Anthony Russo discussed the research that went into that particular facet of “Cherry,” as well as the film’s address of America’s opioid crisis, its chronological structure, and how cinematographic detail enhanced select scenes.

“Cherry” (2 hours, 20 minutes) is currently in theaters and available to stream on Apple TV+.

OP: This is a story that has so much to pack in for a single film. How did that factor into breaking the film into chapters?

Anthony Russo: This story basically covers 18 years of his life. He goes from being a young, 19-year-old kid who’s feeling disconnected to his environment to joining the military and looking for a sense of connection.

Of course, we see him traumatized by violence before eventually turning to opioids. Once the addiction becomes a reality for him, his entire existence becomes about feeding that addiction, no matter the cost of hurting personal relationships. He then has to find a way to walk away from that and find a path toward redemption.

It just seemed like such an epic journey. So, we really tried to break the film up to give each of these really significant life chapters a unique voice.

“Cherry” does indeed have a unique voice, but he also endures experiences shared by so many, be it addiction or post-traumatic stress. Was that an inspiration, in the film’s telling of the story, to leave Tom Holland’s character unnamed?

What was so intriguing about the novel to us is the idea that it’s so subjective to his character’s point of view. He has an inner monologue that remains distinct from his exterior experiences. Part of the motivation of not naming him was simply due to that lack of connection, and there are certainly individuals who can relate to that.

And then, thinking about the opioid epidemic and the experiences people are having — it’s impacted so many lives in some way. That’s one of the reasons in the movie that we did these overhead shots of houses and neighborhoods; we wanted to be evocative of the idea that this is a very pervasive experience. And while we’re only looking at one person’s version of that experience, we wanted to suggest that he’s representative of everybody, that he represents a much larger experience, even though each individual lives through a different version of it.

Staying on cinematography, there were so many subtle visual touches — the ‘WHOMEVER’ recruiter’s name tag, the “Shitty Bank” sign — that added context to particular chapters. Can you discuss the motivation behind that style?

Everything in the film was from Cherry’s point of view, so we wanted to color the world around him as a projection of his inner psychology at that particular moment in the story.

For instance, when he’s young and having trouble with the bank penalizing him for an overdraft, he’s viewing the teller as being unhelpful. So, we chose in that scene to light the teller in shadows to be a projection of how he feels. He’s up against an institution that doesn’t have a human face and doesn’t see him as an individual.

And then with the recruiter name, it’s that impersonal relationship — no human connection, just checking a box and moving on. The bank name, same thing. His relationship to banks deteriorates as the movie goes on, so he starts to look at it, the institution, as an adversary.

With the robberies, he’s never hurting anyone, but he’s still criminally threatening people. So, viewing the bank in this way becomes a measure of having to justify his actions to himself. He needed to think the bank is the bad guy, the bank is evil, the bank is wrong. ‘Therefore, I can rob it.’

This film also included a number of details unique to the experience of a young service member — from the minor to the significant. How did you approach this project to ensure the authenticity of some of those experiences?

We were very fortunate to have an amazing collection of people working with us on the movie who had those real-life experiences.

My brother and I approach our storytelling from a very character-based point of view, so the entire structure of a narrative is designed around that exploration of a single character. I think we approached our research in a similar way. We really wanted to understand the experience on a visceral and emotional level. So, it just came down to talking to people who lived those experiences, then figuring out what spoke to us.

Like any kind of creative process, it involved hardcore research to understand an experience you haven’t lived yourself. Then it comes down to empathy and figuring out how to put those experiences into a movie in a way that connects with audiences.

One connection certain audience members may feel is through the film’s depiction of trauma. Too often, there seems to be a blanket application of PTSD that ignores the individuality of traumatic experiences. To what lengths did your crew go to give trauma a unique voice?

We did a lot — we needed to because these are very serious issues, and if you’re going to take them on, you have to do them correctly and be as honest and as accurate as possible.

The author had some real-life experiences that spoke to the fictional events in the novel, but we wanted to layer it even more, so we spent a lot of time talking to people who’ve suffered from post-traumatic stress in a specific, technical diagnosable way.

We also spoke with loved ones who have lived with people who are suffering from it. We did that to really understand the issue.

Like you alluded to, it’s hard to define what it is from one person to the next. But for us, there is a sort of extreme technical version of it. Like many things in drama, these things become stand-ins for emotions and experiences that many, if not all, audience members can have. Maybe not every audience member has experienced post-traumatic stress, but all have experienced some form of trauma. The emotions that flow from that and the way the human psyche reacts to things — everybody can tap into that at some level.

So, with the experience of going to war, we had some really brave people who were incredibly open about their struggles, about their experiences, and were eager to help us understand.

These are dark things to talk about. It’s hard to talk about trauma. It’s hard to talk about violence. It’s hard to talk about drug addiction. The cathartic effect movies can have on people, as you see these struggles playing out on screen, is that it hopefully becomes a little less of a dark secret and a little easier to talk about these things.

For the movie to have that effect, we had to be faithful to those experiences.

Thank you to director Anthony Russo for taking the time to discuss the filmmaking behind “Cherry.” You can see the film in theaters or stream it today on on Apple TV+.

J.D. Simkins is the executive editor of Military Times and Defense News, and a Marine Corps veteran of the Iraq War.

Tags:

cherry moviecherry russocherry tom hollandcherry movie reviewcherry iraqcherry bookcherry walkertom holland moviesrusso brothersIn Other News