The movie "Unbroken," directed by Angelina Jolie, is based on the book of the same name about Louis Zamperini, whose World War II experiences bring a new definition to the word "harrowing."

Zamperini was a rebellious child, but he grew up to compete in the 1936 Olympic Games and he later became a bombardier in a B-24 Liberator that crashed into the Pacific in 1943. After surviving six weeks at sea, during which he punched a shark in the nose, he was captured by the Japanese and endured two years of torturous captivity.

Author Laura Hillenbrand talked to Military Times about how she spent years researching and writing "Unbroken."

Q: Louis Zamperini survived a plane crash, weeks at sea, a shark attack and years of abuse as a prisoner of war. Does he represent the heartiness of his generation or is his strength unique?

A. Louie Zamperini's saga is breathtaking, but the fortitude he displayed in his ordeal was not singular. His entire generation was forged in the crucible of the Great Depression, a time of staggering and almost universal hardship. The children of that generation grew up into extraordinarily intrepid, self-sacrificing, resourceful men and women who had no sense of entitlement and an almost unassailable resilience.

Reaching adulthood just as the world descended into the most monstrous war in history, these individuals proved stronger than their hardships. Tested as few people ever have been, Louie displayed all of the marvelous attributes of his generation, which is rightly called "The Greatest Generation."

Q: As you got to know Zamperini, what did you learn about how people survive terrible ordeals?

A. For Louie, survival came down to a willful act of optimism. Faced with situations that he was extremely unlikely to survive, he willed away any thoughts of his own demise, focusing instead on how to think his way out of his perils, to prevail over them, always believing there was an answer. He told me that when he was on the raft for those 47 days, attacked by sharks, strafed by a Japanese bomber, starving, deprived of water, he never once thought about dying. I find that an incredible act of will. It's a lesson we can all carry into the crises and struggles of our lives.

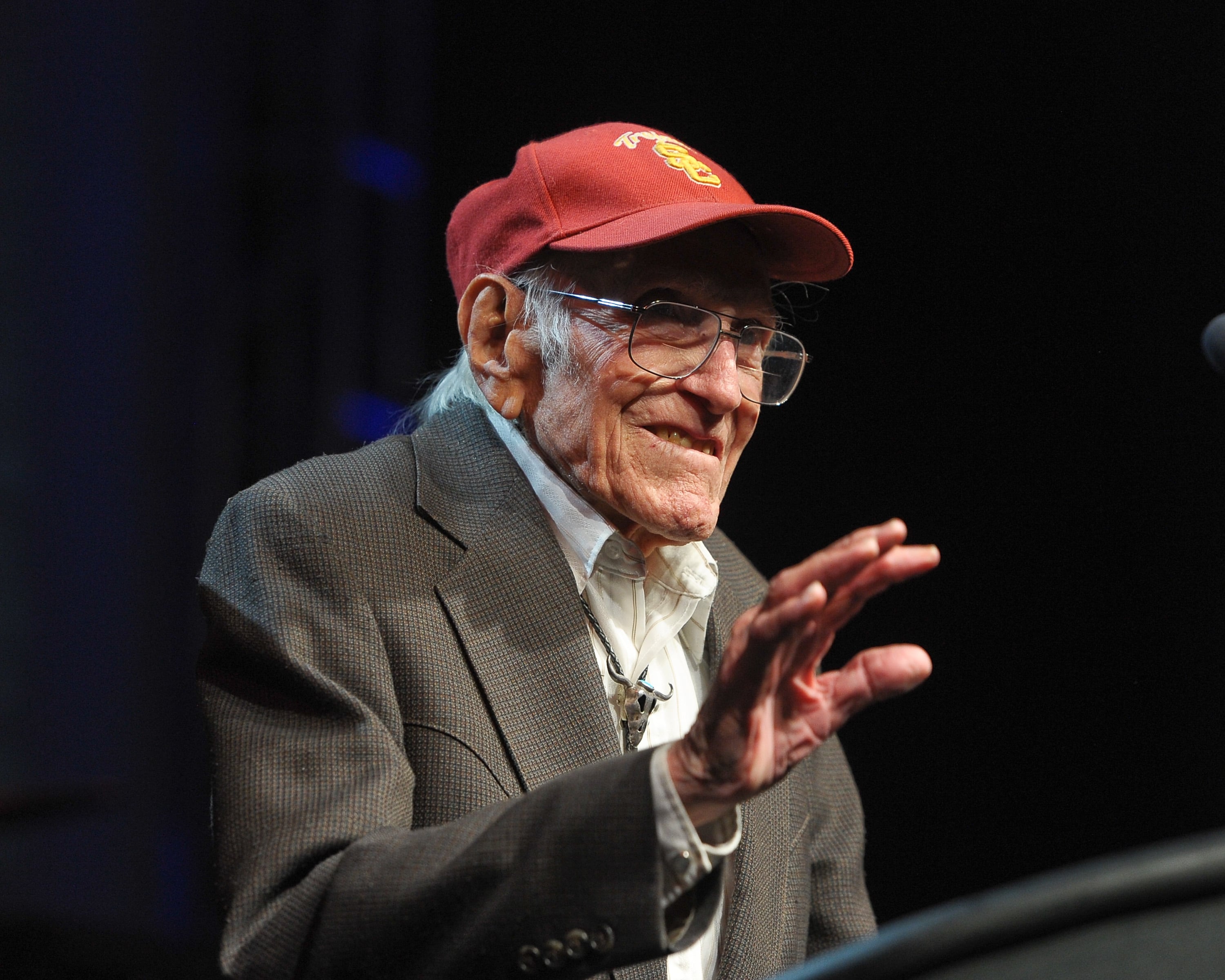

Louis Zamperini appears at an event in Los Angeles in 2011. He died last July.

Photo Credit: Noel Vasquez/Getty Images for USA Swimming

He also believed in preparing oneself for crisis. All his life, he took survival courses whenever he could find them. He was a Boy Scout, and in the military, when optional courses on survival or first aid were offered, he took them. When he was stationed on Oahu, an elderly Hawaiian offered a course in surviving shark attacks. Almost none of the soldiers showed up, but Louie did, and the lessons he learned ended up saving his life. "Be prepared," was a motto of his.

Q: How much did you have to learn about the Pacific war in order to make sure your book did justice to Zamperini's experiences?

A. I learned as much as I possibly could about the Pacific war, and the lives of airmen. It was one of the reasons why I spent seven years researching this book. I wanted to know all about the extraordinary perils facing Pacific war airmen — among them a ghastly 50 percent chance of being killed before completing one tour of duty. I wanted to learn everything about flying a B-24, so I spoke to pilots, engineers, ground crewmen, watched original training films, read innumerable airmen's diaries and memoirs, got the flight manuals for the plane and studied them.

A kind man named Bill Darron brought a Norden bombsight to my house and set it up in my dining room, and I spent an afternoon learning how to operate it. I spent years researching Japanese POW camps, going through masses of documents from the National Archives and other archives from around the world, reading POW diaries, interviewing former POWs.

I went over volumes of statistics on sea rescue, the health consequences for former POWs, every possible subject involving the war. It was a huge undertaking, but absolutely fascinating. I did all of this because I wanted to go far beyond just telling the story of one man. I wanted to place him in history, in his context, capture the texture of it, the emotional background for it, and show the whole Pacific War through his experience.

Q: What lessons does Zamperini's story hold for current U.S. service members and veterans who are dealing with the effects of post-traumatic stress?

![Golden Globes Nominations Snubs and Surprises [ID=20763049]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/1399c21cf1f9e6a9e49bf93c33a9990a1aff4644/r=500x237/local/-/media/2014/12/22/GGM/MilitaryTimes/635548480263650143-AP865183696970.jpg)

A. For many servicemen and women, the war isn't over when it's over. The hell Louie went through after the war was, sadly, very typical of former POWs and veterans of the Pacific War. I think PTSD has been a very common consequence of war throughout history, and we are only now learning how to address it. I think Louie's life story is a beacon of hope for those who struggle with this terrible echo of war.

He was in the very depths of PTSD, addicted to alcohol, suffering hallucinations, prone to fits of rage, destroying his marriage, tormented by nightmares, yet he did find a way out. He found true, lasting, complete peace. I found many other former POWs and veterans who also rose from the depths to find their emotional equilibrium again, and lived joyful lives. There isn't one path out, one answer to every person's struggle, but the beautiful thing is that you can find peace again.

Q: The Pacific war is — to put it lightly — a delicate subject in Japan. What obstacles did you run into when trying to do research about Japanese documents and former Japanese troops?

A. Unlike Germany, Japan has not faced the truth about its conduct in the war. The horrors its military perpetrated, resulting in tens of millions of deaths, the enslavement of POWs and countless civilians, the systematic and officially organized kidnapping and rape of innumerable "comfort women," and the destruction of much of the Far East, is not taught in their schools, and generations have grown up in ignorance of it.

It is a taboo subject in Japan, and I encountered that a lot. I worked with two translators who were indispensable to me, but who asked me to ensure that their names, and any information about them, were never made public, and I have honored that request. They are right to be concerned; there is venomous hostility to anyone who questions Japan's innocence in the war.

But I am so grateful for the assistance of a number of Japanese people who helped me work on this. There were employees of POW camps who spoke honestly and freely to me about what they witnessed. There were Japanese people who have worked exhaustively over decades to expose the truth about the treatment of POWs held by Japan, and they were tremendously helpful.