He's afraid he's got no skin in the game as a drone pilot. And Maj. Tom Egan, played by actor Ethan Hawke, sets out to redeem the career he once had as an F-16 pilot, the feeling he had when he was deployed — but most importantly, his pride.

In the upcoming film "Good Kill," Hawke's character — adorned with 3,000 hours in F-16s, six tours and 200 combat sorties — watches with a wandering eye as "real planes" sit on the flightline and, as he sits with members of the 61st Attack Squadron in "some trailers outside of Vegas" taking orders via from speakerphone. The "good kill" isn't as thrilling, and it empties him — one Hellfire missile at a timehellfire by hellfire.

In "Good Kill," Hawke teams up for the third time with director Andrew Niccol ("Gattaca," "Lord of War") to enlighten for audiences about the story of the men and women who are not permitted to can't speak as freely about their work, not what they do with their loved ones at home, and, sometimes, not with one another.

"It's a weird thing to be actively engaged in battle and be able to pick your kids up from school," Hawke told said in an interview with Military Times Jan. 14. "And [service members] have never had to do that before, and it's worth talking about."

Hawke said this movie, set to debut in May, is one of a few that give audiences a window into modern warfare and new technologies that make it possible to wage war 7,000 miles away.

But the rise of drones — the Air Force prefers to call them remotely piloted aircraft, or RPAs — has come with no shortage of controversy, not the least of which is the secrecy surrounding their use in the war on terrorism and claims that loose policies have led to innocent people being killed.However, Hawke said he couldn't classify RPA pilots by the recurrently used term 'gamers' — a label quickly thrown out in the film as well by commander Jack Johns (Bruce Greenwood) — because gamers have no repercussions for their actions.

"I don't take that as a serious criticism in the movie, because [Johns] goes on to say, 'Make no mistake this is not a game'," Hawke said. "But we all, particularly as Americans, we're faced with new questions. Every generation is faced with new questions and...[new technology] is letting itself into all aspects of the world, including the military.

"What we do, and how we use this technology," Hawke said, "is the question of our time."

Here's the interview, Questions and answers from Military Times' interview have been edited for clarity and brevity:. Military Times has viewed the film.

Q. How did you prepare for this role? Did I mean you have Air Force lingo on hand, so did you consult with drone airmen or other pilots during filming? Did you get to visit a base, or see a ground-cockpit for RPA pilots?

A. I've worked with Andrew Niccol — this is my third time , we met first when I was young he wrote the science-fiction movie 'Gattaca' and he wrote and directed 'Lord of War' about arms trading — and I think the thing that's most impressive about his writing is his research. It's pretty overwhelming. He A lot of being a director is good leadership and giving the cast ; you know he brought in two former drone pilots [from Creech Air Force Base, Nevada,] to work with us everyday, to walk us through all the different machinations of how everything worked and what their experiences were, and he gave us tons of literature. It and it was kind of one of the most exciting elements of my job — getting these very brief, limited educations on such disparate subjects.

What my character's really struggling with is the fact that he's not flying. He really misses flying. For me, ironically, you know what I ended up watching is I found all this great material — documentaries of pilots who were landing on aircraft carriers. [That was] a lot of the training that my character, Tommy Egan, would have gone through. And I was trying to understand what he missed. you know when you see the adrenaline and the difficulty of landing on an aircraft carrier. at night in an F-16. You know the pride one would take in doing that since it's so hard to do. [[[I think we ought to scrap this. F-16s don't operate from carriers]]]//NOTED OUT//OP

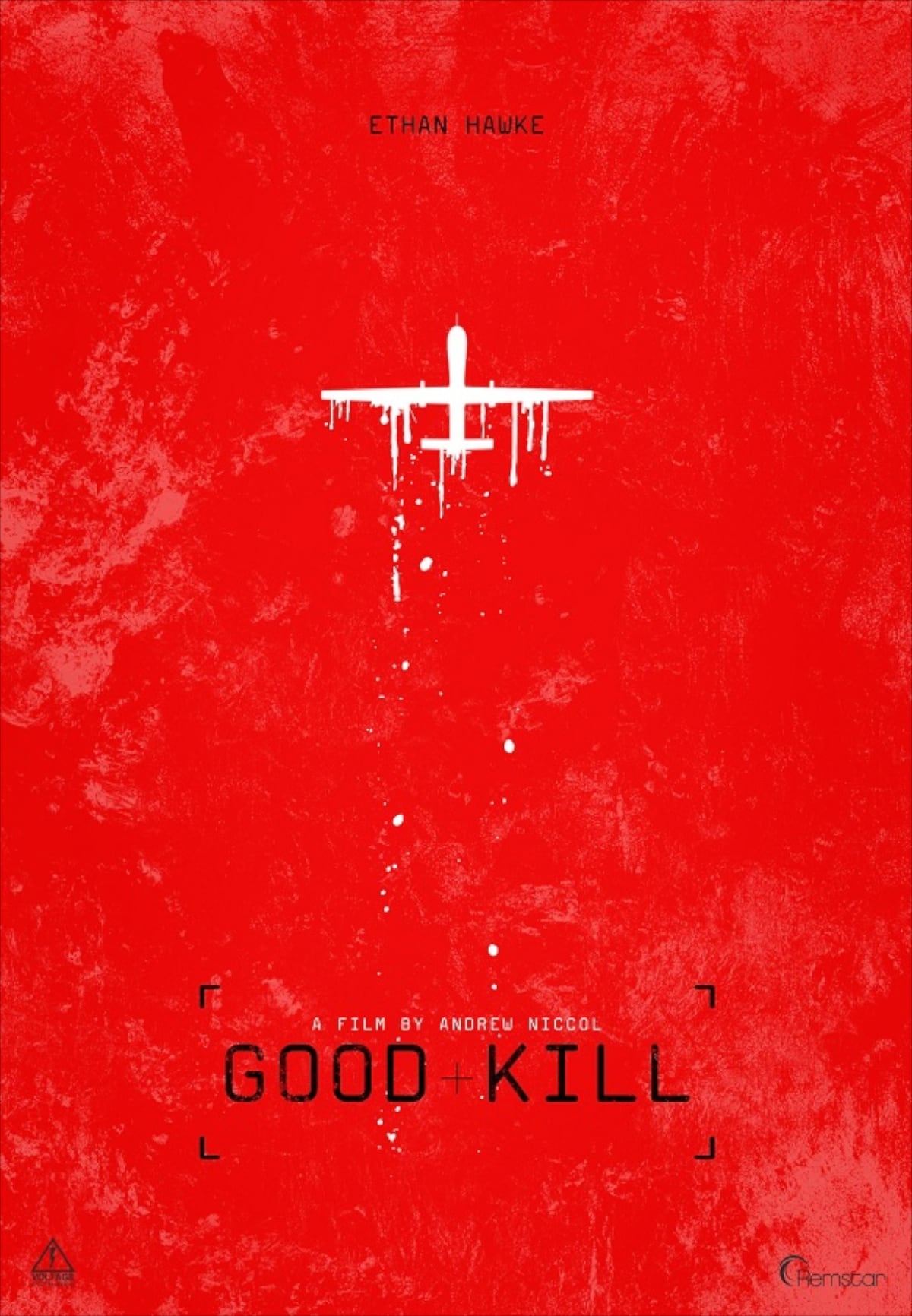

Movie poster for Good Kill

Photo Credit: Promotional poster

Q. You told Entertainment Weekly in September that this kind of feels like a science fiction movie. Why is that?

A. Technology is moving so fast. For people in the military, it probably wouldn't doesn't seem like a science fiction movie, but we still live in a world where we're still watching World War II movies constantly. "Fury" came out this year, "Monuments Men" ... a whole generation has grown up on Vietnam movies and WWII movies, and there's been limited exposure to — despite the lengths of the ongoing war on terror — there's only been a few [modern war films]. The language of cinema is still caught around Vietnam and So So when you see what modern day warfare's looking like, and what new equipment looks like, to civilians, it looks like science fiction.

When you realize that people can wage a war from some trailers in Vegas and have an impact on the ground in Afghanistan, that's just a modern idea. Probably dated for the military, but I think the mass amount of civilians that read about a drone strike in the New York Times kind of have no idea what they're reading.

Q. How realistic do you think the movie is?

A. I can't really speak to that, but If the history of movies has taught us anything, I'm sure we got a ton of things wrong. I know that every effort was made to be representative of the equipment, and the time "Good Kill" was set in 2010, but the movie is not nonfiction, it's not a documentary. … The job of movies is to create stories to create dialogue, give a voice to the voiceless. It's really to inspire a healthy dialogue, and I think that's what the job of movies are. I would love it if what we got right is more than what we got wrong. , but its not a documentary and, invariably, We were given such little access that it made it hard for obvious reasons. The military doesn't want every movie company marching around their bases. It would counter to their needs and desires.

Q. Bruce Greenwood plays your commander (Jack Johns) in this film. What would you say he is for you in this movie, aside from someone you have to take orders from?

A. I think it's somebody my character respects. He's my commanding officer and I have a respect for him. Most of us have a kind of, a slight ... intrinsic , you know, mistrust of anyone who's always telling you what to do. But I think that in general that they really like each other and there's a great fondness between the two of them. And I think it's why my character ultimately, in a way, betrays him and it's very disappointing to both of them, I think.

Q. At one point you ask Greenwood, "Why do we wear flight suits?" and the question remains unanswered. What was that meant to represent?

A. Great writing asks questions, it doesn't give answers. I don't think Andrew [Niccol] has an answer for what the drone program should be doing. It's just a very relevant to where the war is today. … And my favorite kind of writing ends in a question mark, particularly when you're dealing with the volatile nature of politics. Whenever I sense from the movie that it has an agenda, I resist it. I like that left in a film that leaves a question mark, and I think that's what that scene is. His commander has lost his way, and he doesn't really have answers that come really easy to him, for his character. So that's what that scene is. Ending in a question mark.

Q. You're the main character in the film, controlling the RPA and Hellfire missiles, but what do you think the rest of the characters bring to the dynamic of your crew?

A. The essential elements of teamwork are consistent with how you work well with others, so whether we're actors or drone pilots, there's a dynamic where you're all relying on each other. And the natural mechanics of those aircraft, each one has different, technical responsibilities. For us as actors ... there's always a balance ... you also have a sort of responsibility to tell, for lack of a better word, a spiritual truth about it, meaning you get the spirit of it right, what it will feel like — and make it entertaining to watch.

Ethan Hawke talks about 'Good Kill' during the 2014 Toronto International Film Festival.

Photo Credit: Chris Young/AP

Q. Your character is trying to understand not only his career in the Air Force, the term "pilot," but also his identity. Do you think audiences will grasp who you are and what you've learned by the end of the movie?

A. This is all still so new for me. To be honest, I haven't done very many interviews about this movie. ... We showed the movie for the first time at the Toronto Film Festival, gave a few little interviews about it, but my general impression is that most people have no idea what you're talking about when you're talking about drone strikes. They don't know if it's being fired from a satellite, or if it's a laser gun. It's amazing how little the average civilian really understands about it. And as this program takes on more and more responsibility, I thought it was an exciting opportunity to tell a story about it. But what audiences take from it, what the military takes from it, it really remains to be seen.

Q. What do you want audiences, especially the military, to take away from this film?

A. Our job is to create dialogue, the artisans of the world. Like when you're at a dinner table, what do you talk about at dinner? I miss a certain kind of political film, and I miss a certain kind of healthy, political dialogue. ... Part of the job of the arts is to give people a healthy discourse. Some people will like the movie, some people won't like it, and somehow in that dialogue, some real truth will come out.

Q. From the media and now especially from doing this movie, how do you feel about the U.S.' position on drone policy?

A. ProbablyI feel just as confused as the people who have to make those decisions. There's a great line that Bruce Greenwood says, that, "It might just be the best worst option." What I believe, it's clear that there's a new weapon, and whenever there's a new weapon in the history of warfare — my brother's a colonel and a Green Beret, so he's often educating me about this stuff — the rules change, and I think that this is a new weapon, and it's a weapon that a lot of people in the public don't understand. And they sometimes don't understand its impact on the service members who have to use it. For the public to have an opinion, they have to have some knowledge about what these men and women are going through, because the service members can't speak for themselves — they have their duties to do. So we as artists can talk more freely than they can. And I think it's kind of our job as artists to talk more freely about it to do so... There are scary things when you start changing the rules, and I think they need to be talked about. I don't consider myself as having an expert opinion, I was just really interested in playing an airman who I thought was in a completely new situation.

Q. What did you personally take away from doing this film? , and how will it affect future films you do down the road?

A. Actors love movies and good drama. We love storytelling, that's what we do. I'm excited to be a part of a generation that tells stories about what's been happening in the last 10 to 15 years. It's a really exciting, wild time in history that we're living in ... my brother joined the military right out of high school, and I remember us talking about, "God, we live in such a boring time." You know, in the '90s, which is such a young person thing to say. But boy, has that changed. We are living in an incredibly volatile, incredibly interesting era with a lot of tough questions. There's been a lot of heroes, and a lot of villains ... so, what I take away from it, is I'm excited to make more movies. To tell more stories.