Editor's note: The following is a personal opinion piece. The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Navy Department, Defense Department or federal government. The author is not employed by Military Times and the views expressed here do not necessarily represent those of Military Times or its editorial staff.

I was born in one of the seven countries affected by the recent executive order on immigration. My chain of command has advised me to avoid specifying which country in order to lower the risk of reprisals against my family.

In 2001, not long before my 19th birthday, my immediate family and I were admitted to the U.S. as religious refugees. In my home country, my family had been subject to persecution for years — our possessions were confiscated, we were kicked out of jobs and schools, and many family members were sent to prison.

My mother supported us by working as a private English tutor, and she was repeatedly told to stop. When she continued to teach, the government put pressure on her by briefly arresting me, threatening to arrest my siblings and sending men to follow us on the streets.

Filled with fear, my mother made the difficult decision to leave the country we called home. We did not know what would come next, but we knew that we could apply for resettlement as refugees. We crossed into Turkey and were sent to a small town to wait for processing. After almost a year of interviews and applications, we were filled with joy and gratitude when we learned that we had been granted entry to the U.S.

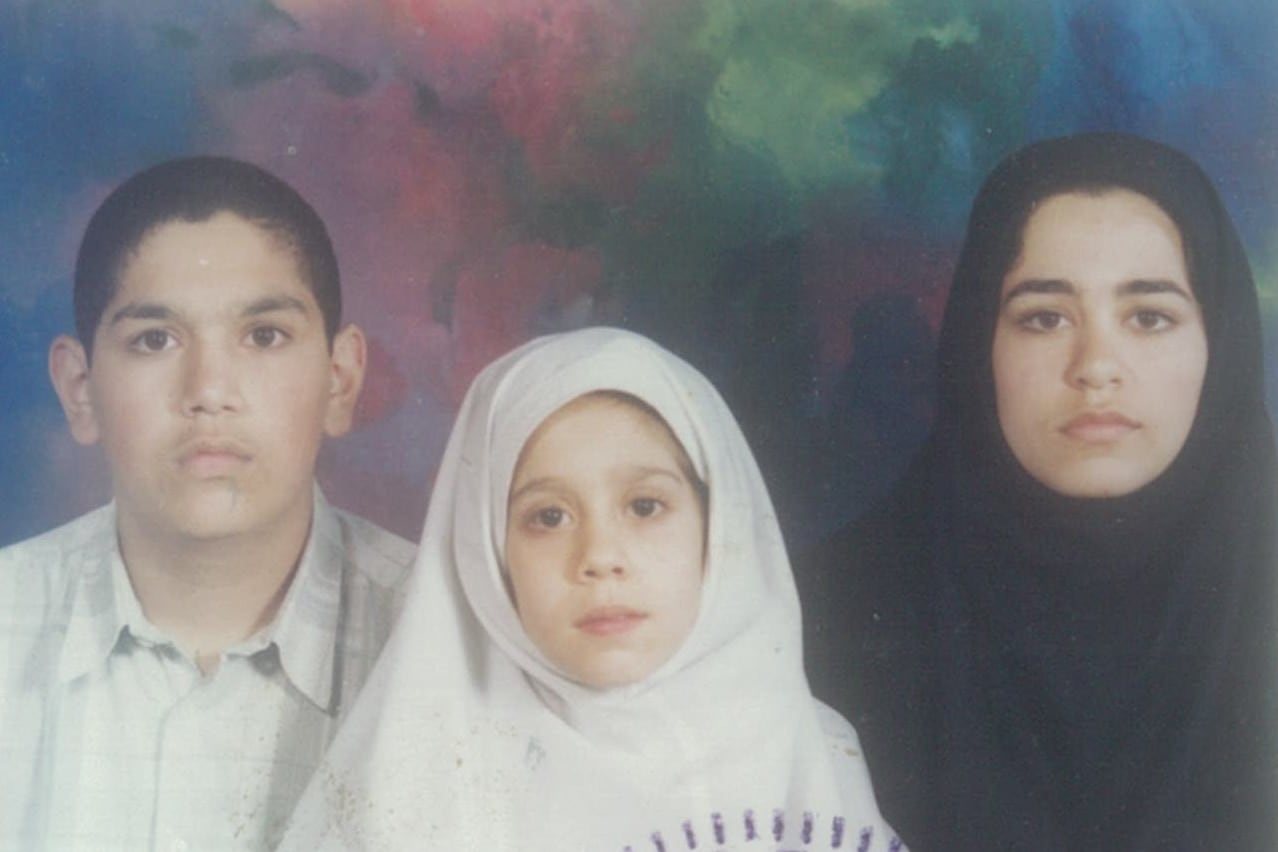

Lt. Shamis Fallah, right, with family members when they arrived as refugees in Turkey.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Sunshine Sachs

We arrived with no money and only my mother's English, but the people of America took us in. A generous family from Southern California gave us incredible support: they included us in their gatherings, helped us apply to schools and jobs, and comforted us when we were overwhelmed. Our families became inseparable, and we still celebrate Thanksgiving and Christmas with them every year.

The U.S. gave us freedom, and also the opportunity to pursue further education. I realized that here, I would be able to follow my long-held dream of becoming a physician. A fellow refugee who was serving in the Navy told me that, if I joined, the Navy could support me through medical school. I saw that this was not just a path to my dream, but also a way that I could be of service to this country that had done so much for my family.

I became one of the tens of thousands of immigrants (and, I believe, one of thousands of refugees) proud to call myself a member of the U.S. armed forces. Specifically, as a physician, I am proud to serve a population of patients who have themselves dedicated their lives to service.

My extended family is still split between my home country and the U.S. — some have been able to come over, and others are either not allowed to join us or feel it is their duty to stay despite the persecution.

Qualifying for legal permanent residence allowed my grandparents to travel back and forth to help hold our family together. They have been able to come to San Diego to spend time with my daughter, their first great-grandchild. Meanwhile, on the other side of the ocean, my aunt faces a multiyear prison sentence for supposed anti-regime activities, and my grandparents have also been able to go back to support her family.

Lt. Shamis Fallah, right, with her husband and daughter.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Sunshine Sachs

The executive order on immigration, and especially the unpredictability of its enforcement, has been painful for my family. It has been unclear at times whether even family members with legal permanent residence here in the U.S. were free to come and go. When I see travelers from my home country with legal visas detained at the airport as if they were criminals, I know that could easily be my elderly grandparents.

Eventually, I expect the rules will stabilize, and we will adapt — but I cannot avoid feeling that our adopted country is suspicious of us. Whatever the grounds for this suspicion, the immigrants I know are America's greatest advocates abroad. When my grandparents travel back and forth between the U.S. and my home country, the connections they make are powerful.

The story of America that they tell is one of freedom and acceptance — directly contradicting the negative messages broadcast by foreign regimes. This is the case for all of the refugee families I know: the connections they maintain to the places they fled from serve to promote American values.

I do not know the ideal immigration or visa policy, but I do know many refugees, and I know that when America shelters us it earns our gratitude and makes us into American patriots.

Lt. Shamis Fallah is a naval flight surgeon who served with Marine Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Squadron 1. She is on active duty training as an ophthalmologist at Naval Medical Center San Diego.