First lady Jill Biden on Nov. 13 announced the launch of the White House Initiative on Women’s Health Research to highlight the goal of fundamentally changing the way women’s health is approached and funded.

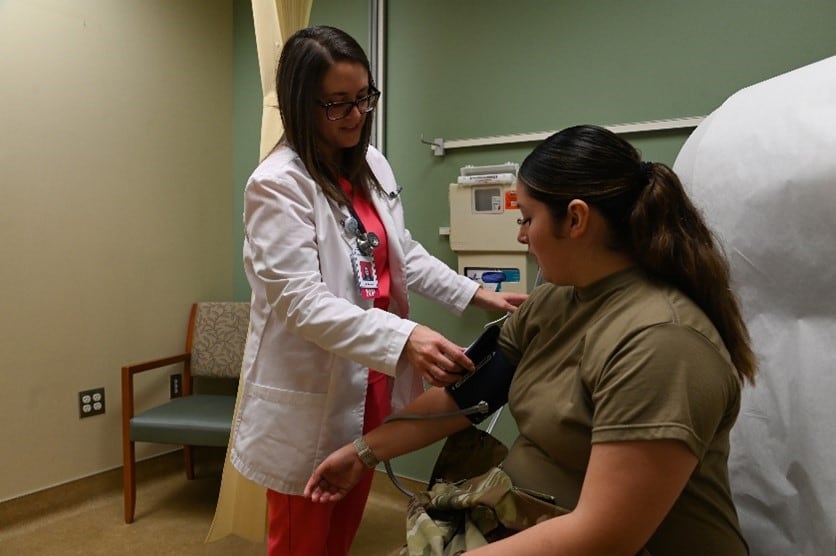

The effort is designed to provide opportunities to improve health and performance outcomes for all women, including — perhaps most importantly — women in the military.

The scarcity of research on women’s health is not a new problem. In medical and human performance research, women are frequently omitted from the data. When women are included, they are regularly treated as interchangeable with men. Yet women are not small men — they have different physiological and hormonal requirements yielding distinct nutritional, injury prevention, training and recovery needs.

Now is the moment for the federal government to invest in optimizing women’s health and performance in the military. Women currently comprise 17.3% of the total active duty force, 19.2% of the officer corps, and 17% of the enlisted corps (with variation across services).

In the Post-9/11 era, more than 300,000 women deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan, a number comprising 11% of all deployed service members. More than 9,000 women earned Combat Action Badges in Iraq and Afghanistan — many prior to the lifting of combat job restrictions on women. What’s more, the services are increasingly turning to women as qualified military recruits in the wake of a challenging recruiting environment. Female high school students are more likely to meet the standards for military service, as they graduate high school at higher rates than their male counterparts and are less likely to have a criminal record.

The lack of research attention given to the health and performance optimization of women in the military yields suboptimal results for both the military services and women in uniform. The U.S. military observes outcome data indicating women are at higher risk for musculoskeletal injuries, particularly during basic training. The data on female service members’ injury rates has, at times, been used to justify why women should not be allowed to enter into combat roles. Yet what such information fails to capture are the ways existing policies, practices, and equipment hinder female performance optimization in the military.

For example, military-issued protective gear — including body armor — was designed for male physiologies. As such, women in uniform are subject to ill-fitting equipment, resulting in gaps in coverage and an improper balance of weight on women’s musculoskeletal frames.

Further, women in the military use oral contraceptives at higher rates than their civilian counterparts, in part to ensure that women’s natural menstrual cycles do not affect their ability to train at the same pace as their male peers. A growing body of research is examining the potential impacts of the use of oral contraceptives on the physical performance of women.

Weight standards — measured every six months, in addition to physical fitness testing standards — are associated with a prevalence of eating disorders and disordered eating among women in uniform. In an effort to meet height and weight standards based on male physiology, some women in uniform are trading away strength in order to “make tape.”

The question of the moment is not whether the challenges facing women in the military should preclude their participation, but whether and how new approaches to female-specific research on health and performance optimization might improve the readiness and lethality of our female troops.

The military need look no further than the ways in which U.S. Olympic, professional, and collegiate athletic organizations approach their research, evaluation, and protocols for individual athletes: tailored nutrition and recovery protocols, custom equipment, and training cycles that account for the impact of hormonal cycles on performance.

An improved approach to health and performance optimization research on women in the military doesn’t just benefit female service members; it fundamentally changes the paradigm of the data, metrics, training, and treatment research necessary to optimize the performance of all tactical athletes at the individual level — men and women alike.

The White House’s focus on women’s health research presents an opportunity for the entire Department of Defense to identify ways in which their own research can better harness and unleash the readiness and lethality of the growing number of women in uniform.

Katherine Kuzminski is the deputy director of studies and the director of the Military, Veterans, and Society Program at the Center for a New American Security.

Have an opinion?

This article is an Op-Ed and as such, the opinions expressed are those of the author.

If you would like to submit a letter to the editor, or submit an editorial of your own, please email opinions@militarytimes.com for Military Times or our services sites. Please email opinion@defensenews.com to reach Defense News, C4ISRNet or Federal Times. Want more perspectives like this sent straight to you? Subscribe to get our Commentary & Opinion newsletter once a week.