There is a concept called “bulldozer parenting” that refers to parents who knock down every obstacle for their children before they get a chance to struggle. While this is meant to protect their children from short-term harm, psychology lecturer Rachael Sharman observed it “ultimately results in a psychologically fragile child, fearful and avoidant of failure, with never-learned coping strategies and poor resilience.”

These same good intentions can lead to senior leadership “bulldozer parenting” our soldiers, and the troubled Army Combat Fitness Test (ACFT) implementation is an example of that.

The legacy Army Physical Fitness Test (APFT) was designed based on a Cold War era assumption that ground combat was a thing of the past, an illusion that left many soldiers physically unprepared for what they faced during the Global War on Terror. The initial version of the ACFT, to address lessons learned in combat in Iraq and Afghanistan, represented a significant challenge for the force.

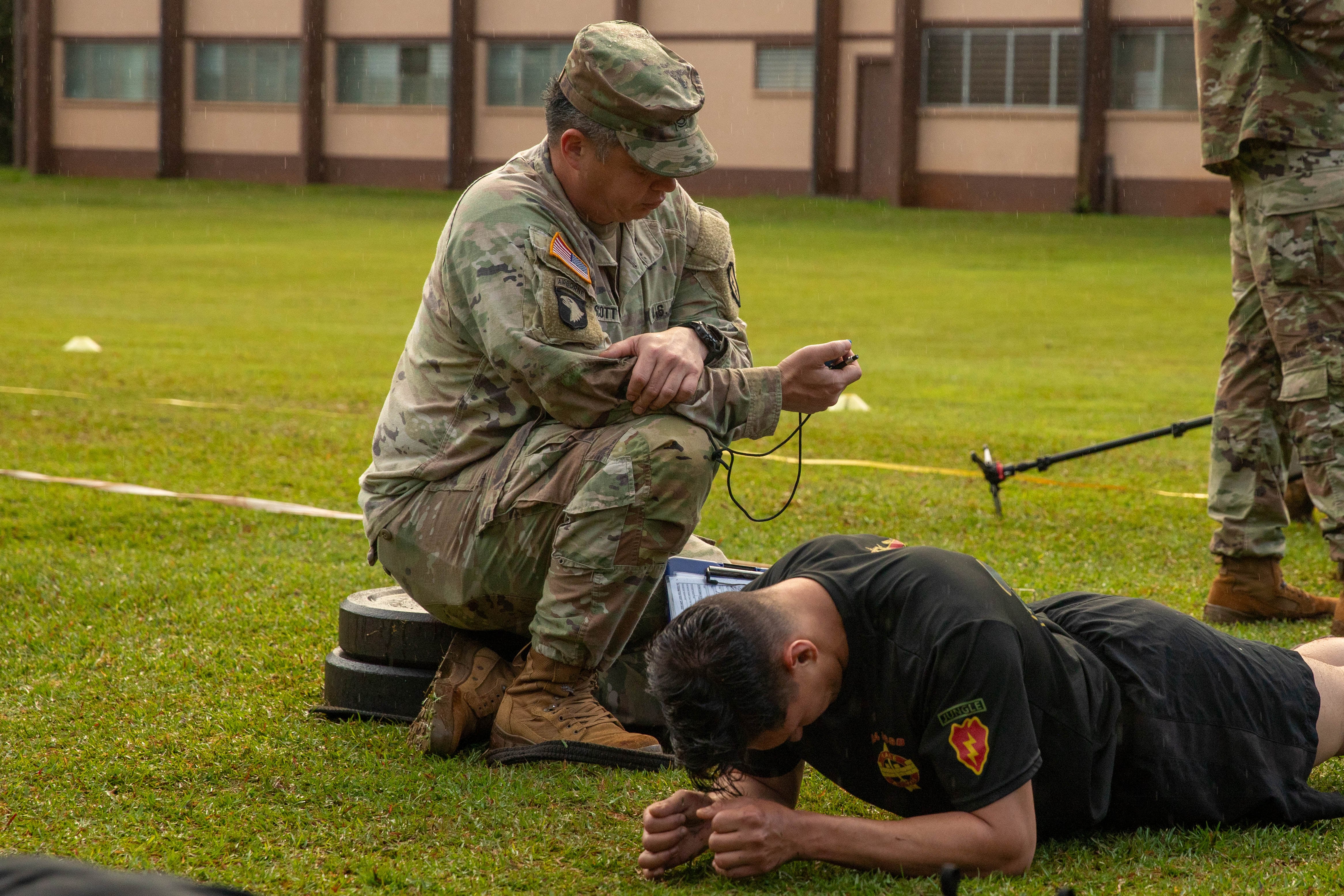

Predictably, the raised expectations were met with an initial wave of failures. Despite leg tucks being in training doctrine for over a decade, initial ACFT trials showed that 60% of women and 8% of men failed to complete one repetition. Army data later revealed that seven months into the ACFT implementation these failure rates had dropped to 22% of women and 2% of men. That same data also indicated that soldiers failed the run at an even higher rate, 22% of women and 5% of men, despite the passing standard getting easier compared to the APFT for most demographics.

One way to fix this would have been to give soldiers time and resources to rise to the challenge. Instead, under significant political pressure, the Army chose to remove the leg tuck, and to rewrite score charts to guarantee most soldiers passed.

This also sent a clear message that future attempts to raise standards would be canceled if soldiers failed frequently enough. This was the opposite of what the ACFT was designed to address — a need for tougher training and higher standards for a new era of combat.

The test began as a criterion-referenced assessment with Army-wide field tests in 2018, meaning the standards were based on predictable demands stemming from combat operations or one’s occupation, though officials deliberately set minimum passing scores lower than these demands. After these adjustments it became a norm-referenced assessment, meaning scores were adjusted to reflect average performance levels.

Remember, without any actual changes to training or policy these were the same performance levels that leaders identified as insufficient when they first directed the ACFT’s development. Also, since this was a pilot study, soldiers had little incentive to push themselves in the test. Evaluators collected the data when there were no consequences for poor performance or rewards for high performance.

Despite the congressionally mandated RAND Corporation report finding that the ACFT passing scores were designed to be easier than real-life tasks facing soldiers, and observing that it was already improving Army fitness culture, leaders were extremely concerned with initial pass rates.

The Army challenged the force with a new fitness standard, yet despite widespread improvement as units and individuals adjusted their training, the Army rewrote the score charts to ensure the test would be easier to pass. The RAND study even observed that very few soldiers had even had a second opportunity to test at the time revisions were made, but those who had showed significant improvement.

If the test was introduced to address deficiencies in fitness, how is it acceptable to base the standards on current performance? The Army introduced more relevant components of fitness, and then it promptly bulldozed those standards to save soldiers from struggling.

So what are we left with?

While higher scores remain challenging, passing requires a mere 10 pushups, a 22-minute 2-mile run (for the fastest demographics), and a sprint-drag-carry that can be walked. If you can’t run due to injury, the row standard is so slow it would put you in the bottom 5% of competitive 10-year-olds. This is particularly concerning since the updated policies mean that a soldier medically disqualified from participating in every event of the test could be deployable based on the row alone.

Noting the newly lower standards, Congress directed the Army to establish higher passing scores for combat roles. Previous iterations of the ACFT did exactly that, establishing a single baseline Army standard, but holding more physically demanding jobs to higher requirements. For example, in 2020, the passing 2-mile run time for male and female soldiers between 17 and 21 was 21 minutes. By comparison, today the passing run time is 22 minutes for male soldiers between 17 and 21, and 23 minutes and 22 seconds for female soldiers in that age bracket. The passing score for run times was not increased because they were unrealistic, they were changed because of outcry when people found them challenging.

There must be a balance. The Army has to take care of its people, but resilience is not developed in resilience classes — those lessons matter, but actual growth comes from applying lessons learned through hardship. Finding yourself in combat without the requisite resilience — physical, mental and spiritual — has consequences far beyond failing a fitness test.

The Army can knock down obstacles at home, and that might make people happy for now, but we have a responsibility to our soldiers to ensure we don’t send them into harm’s way unprepared. The Army can continue its current path, lowering the bar until everyone can step over it. Or it can set expectations higher and watch people rise to meet them.

Alex Morrow is an Army Reserve officer with experience working in several military human performance programs for the Army and the Space Force. He hosts the MOPs & MOEs podcast, which can also be found on Instagram at @mops_n_moes. The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official position of any organizations he is affiliated with He can be reached at alex@mopsnmoes.com.