When you’ve walked the earth for decades, it’s easy to take standing for granted. After all, very few, if any of us, remember what it was like to push or pull ourselves up as babies and stand on wobbly legs for the very first time.

Some people, however, live with the desire to relive the experience of standing for what feels like the first time. Those I’d encountered were usually military veterans of all walks and stations in life. All bound together by the vivid memory of their last best day, when walking was as natural as breathing. Until a car crash, training accident, sporting collision, awkward fall or a sniper’s bullet left them unable to run, walk or simply stand, thus changing their lives forever.

This reality for them colors my own thoughts and reality when I wake up every morning. I get dressed and transfer into “my legs,” the power-assist wheelchair that is never more than an arm’s length away from me. My lifeline for the last 17 years as I go through my daily routine. Eventually, the muscle memory it took to push that wheelchair would replace what it felt like to walk as life veritably rolled on.

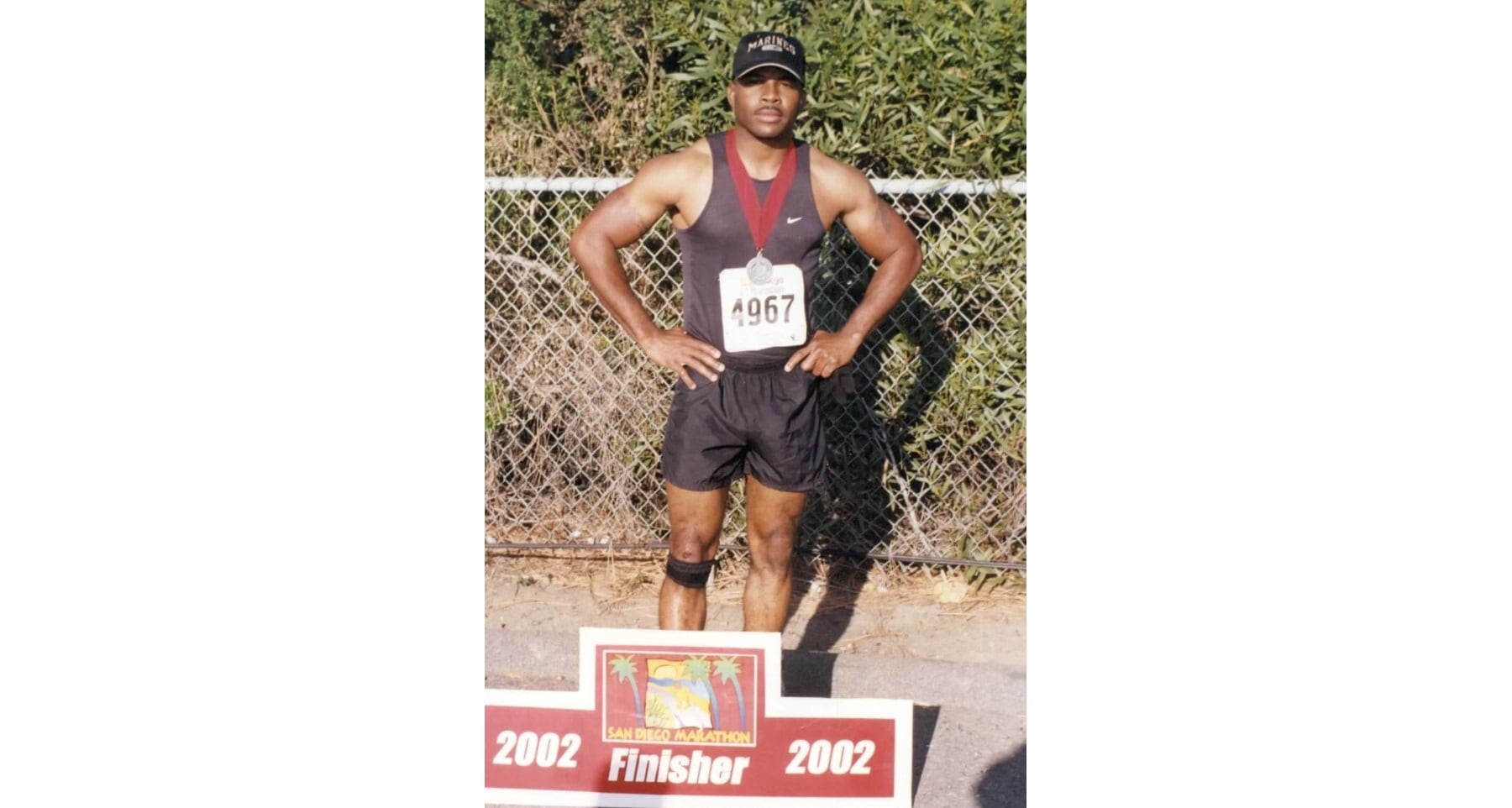

Many of us who live with paralysis do just fine: We graduate from college; drive cars; start and raise families; build social networks; marry; get jobs — in other words, live an otherwise normal life — a “new” normal, which perfectly describes my own life after suffering paralysis in February 2002.

“New,” however, because I now had to deal with inaccessible public buildings, airlines damaging my wheelchair during flight or elevators in metro stations that were often down for repair. Worse yet was the realization that the dignity of standing eye to eye in front of someone, or using my 5-foot-11 stature to make my presence felt, were now distant memories. It was a reality I had to accept because I had no choice — that is, until very recently.

I’d known for years about wheelchairs and exoskeleton devices that help veterans with missing or paralyzed lower limbs stand. In fact, I’d helped several obtain standing devices in my capacity as a veteran advocate who was well familiar with the VA benefits and health care systems. But seeing myself in one of them seemed out of reach for myriad reasons — or, perhaps, excuses.

“I’ve done just fine in my wheelchair all this time — why disturb what I’d long accepted?”

“Those devices require maintenance and break down occasionally. Do I really need the headache?”

They cost too much, become outdated by the next iteration too quickly, and require too much of a hassle to get one at VA expense. Is my dignity really that important?”

A fellow veteran, Brad Soden, of the National Marine Corps Business Network and LEVO USA, would answer those questions in a surprisingly stark way that I didn’t see coming.

The random text that I’d received from Brad one afternoon couldn’t have come at a worse time. My to-do list at work kept getting extended all week by conference call after conference call and meeting after meeting, in addition to all of my back-burnered projects that weren’t aging well. On top of it all, the first major snowstorm of the season was about to shutdown the D.C. and Virginia areas, which would serve to sabotage any progress I’d hoped to make.

Now, Brad had just informed me that a veteran nonprofit and wheelchair company want to donate a LEVO C3 Standing Power Wheelchair to me. “By the way,” he continued, “a LEVO rep will be at your house in two days to test a demo, take your measurements, and deliver a customized standing chair to you, funded by the guys at the National Marine Corps Business Network.”

It took a moment of disbelief, then anxiety, then pessimism, then hope, and finally acceptance to wrap my head around what was about to happen. Standing up. Me. After 17 years. I’d rolled across graduation stages at the University of San Diego and Harvard Business School. I’d rolled on beaches in Puerto Rico, Jamaica and Aruba. I’d testified before Congress, competed in adaptive sports, delivered commencement and keynote addresses, and held my infant son for the first time — all in a wheelchair.

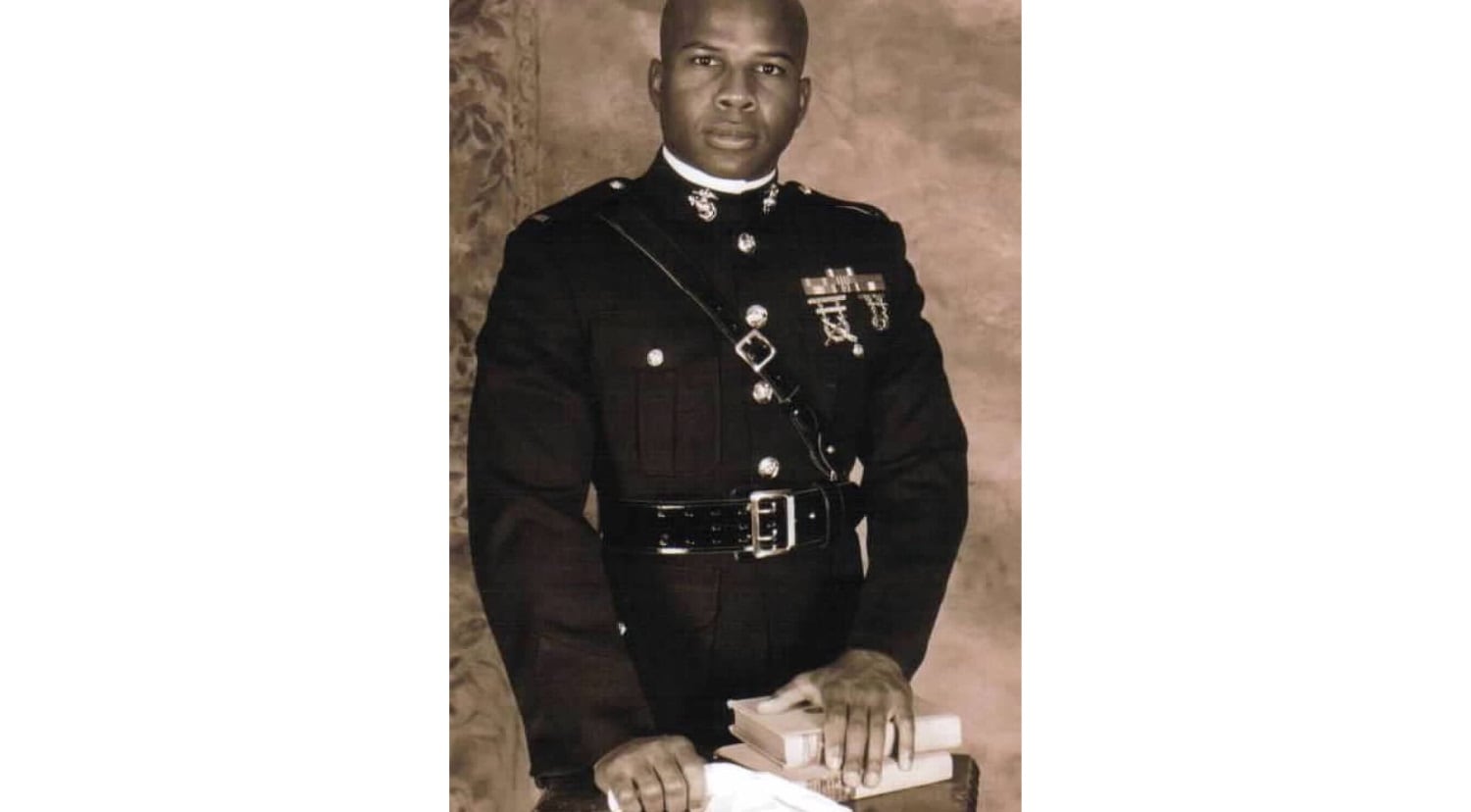

Now, I faced the intimidating prospect of reconnecting with the Marine who stood at attention whenever the national anthem played. Or stared into the sobering gaze of over 400 young Marine Corps recruits I’d trained as I shook their hands on graduation day. I was about to reincarnate the Marine — the former me — who I thought had died in the violent crash 17 years ago that left me paralyzed.

Two days later, I watched with nervous excitement as the LEVO representatives unloaded the standing power wheelchair in my driveway. The moment felt surreal as they followed my wife, Tammie, into our kitchen and began to explain the chair’s features and functions, very matter of fact, like a cardiac surgeon bluntly explaining how she was about to perform a triple bypass right before the anesthesia kicked in. I transferred into the chair, strapped in, and reflected on the last 17 years of my life in about 17 seconds as I prepared to relive a moment I hadn’t had since I was 10 months old.

To explain to someone, who has never experienced paralysis or lower limb immobility, what it feels like to slowly rise to your feet after almost two decades in a wheelchair would be like trying to explain color to a person born blind. So I didn’t try. I simply pushed the joystick forward and ascended. I could feel every muscle in my legs stretching and bones straightening until the chair’s standing feature brought my body perpendicular to the floor for what seemed like the first time ever. I was standing again!

I don’t know what it feels like to win a billion dollars in a lottery or play the lead role in a blockbuster action movie. But no experience could compare, in my view, to seeing the look on my 5 year old’s face when he saw me upright for the first time in his life. Or the tears that poured from my wife’s eyes as she looked up at me instead of down while we tightly embraced. My first thought in that moment was “every veteran who has suffered paralysis should have this experience.”

My second and final thought that day: the person inside of you doesn’t die when you face a life-altering circumstance. He or she simply waits until you’re ready to be stronger than your excuses and literally take a stand when life presents that opportunity.

Sherman Gillums Jr. is a retired U.S. Marine Corps officer and chief advocacy officer at AMVETS, a congressionally chartered national veterans service organization representing the interests of more than 20 million veterans.