After close to 18 years of war, one will struggle to find a single American who believes that continuing the conflict in Afghanistan serves the U.S. national security interest.

The war in this Central Asian country has been defined by blood, sweat, and tears on all sides, with a grinding contest for power between the Taliban and the Afghan government stuck in a permanent state of inertia. The United States, having sacrificed so much already, doesn’t have the energy, the patience or, frankly, the interest in investing more military resources into an unsinkable stalemate.

Years of war have not paved a path to peace. Neither the Taliban or the Afghan security forces possess the military strength to subjugate the other to their terms or win the battle outright. The recent fighting in the northern cities of Kunduz and Pul-e Khumri, in which the Taliban pushed into the area only to be driven back by air power and an Afghan army counteroffensive, is a sad metaphor for the grinding stalemate that has long defined the war. The reality is that diplomacy is the only solution if the Afghan people wish to build a more peaceful future for their children.

RELATED

It is also true that negotiation is also the most effective way the United States can begin divesting military resources from the war and begin right-sizing its presence. The Trump administration’s decision last year to open a direct line of communication with the Taliban was a belated acknowledgement that Washington had no alternative left but to sit down with the insurgency and attempt to settle on a good-enough arrangement that both extricates U.S. forces and refocuses energy on the top objective — ensuring Afghanistan doesn’t become a sewer for terrorists bent on attacking the United States.

Nobody likes talking with enemies. To go from shooting at your adversaries to talking with them is an uncomfortable and downright painful transition. Compromising with the same combatants who are responsible for your buddy’s death is jarring. But none of this is an excuse for avoiding negotiations, because too often the absence of diplomacy results in even more casualties in the future.

RELATED

As U.S. Ambassador and Special Representative Zalmay Khalilzad no doubt understands, a successful negotiation requires incredible patience and immense fortitude. One cannot reach an agreement without them, particularly when the underlying context involves a war nearly two decades in the making. An absence of either quality can turn a tough diplomatic process into a pointless dialogue of the deaf, closing whatever slim opportunity there is to make forward progress.

There have been numerous diplomatic starts and stops throughout the war. The current talks in Doha have proven to be a once-in-a-generation opportunity for the United States to chart a peaceful exit-strategy from this conflict. It would therefore be the height of imprudence for the Trump administration to hold out for the perfect deal. Whether we like it or not, the Taliban is part of Afghan society, will remain so in the foreseeable future, and will need to be incorporated into the Afghan political system. Washington will need to offer concessions on U.S. troop levels if it hopes to extract concessions of its own, including on everything from counterterrorism assurances from the Taliban to the insurgency’s participation in what will be fundamental intra-Afghan talks about the country’s political future.

RELATED

Yet, just as it would be foolish for Washington to make the perfect the enemy of the good, it would also be foolish for the U.S. to assume the Taliban will implement its promises. While the Taliban have learned a hard lesson about what can happen when you get into bed with foreign terrorist groups, the organization is anything but a trustworthy party. Some type of monitoring and verification mechanism must be built into any deal in order to detect violations when they occur. Preferably, this mechanism would be multilateral and bring Afghanistan’s neighbors into the process, each of whom has just as much of a national security incentive as the U.S. in preventing the country from becoming a terrorist haven. Politically, President Donald Trump will find it difficult to sell a deal back home without such a system in place.

The sequencing and pace of the U.S. troop withdrawal and how it is synced up with an intra-Afghan peace agreement is critical and likely one of the most complicated items of the negotiations. Withdraw too fast, and the Taliban will use it to their advantage. But withdraw too slow, and hardliners within the Taliban movement will use it as justification to spoil the process with more violence.

The United States will also need to maintain an intelligence and adviser capability in Afghanistan during the transition to comprehensive intra-Afghan negotiations. The sad truth is that terrorists will continue to make Afghanistan a home, even if Afghans solve all of their grievances and strike a peace agreement. Therefore, the U.S. must keep eyes and ears on the country by utilizing its considerable global intelligence capability, maintaining a robust adviser capability, and dedicating a quick-reaction force to reinforce the ANSF. This can be achieved with a force posture smaller than the 14,000 U.S. troops now operating on the ground.

RELATED

As talks enter their final stages, there are still a lot of unknowns. We don’t know if the Taliban are at all interested in treating Afghan government officials as serious negotiating partners. We don’t know how many Taliban fighters will defect to more extreme groups, a development that is already happening and may very well increase as the dialogue proceeds. We can’t be certain a peace accord between the various Afghan parties is even possible or whether it is a figment of our imaginations.

What we can be sure of is that this long chapter in American military history needs to end. After so many years, the United States finally has the opportunity through patient, bare-knuckled diplomacy to end it.

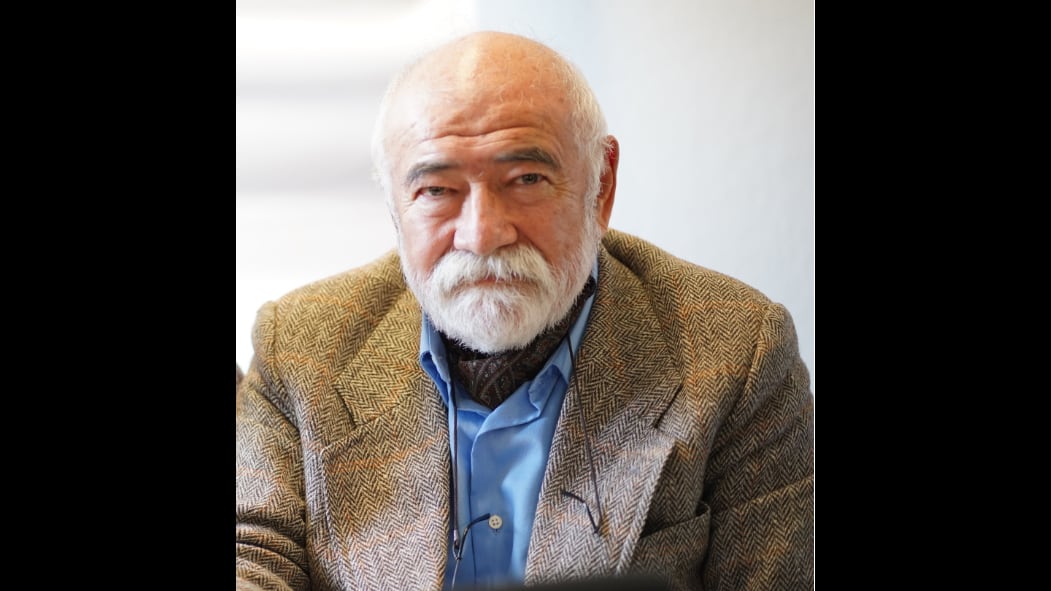

Retired Maj. Gen. Rick Martin served in various command, logistics, and political-military advisory positions within the Air Force and on combatant command staffs. He is a fellow at the American College of National Security Leaders.