If anyone has doubted the importance of child care and youth programs for military leaders and families, the pandemic has likely dispelled those doubts.

The biggest lesson of COVID-19 is “you can’t separate child care from mission readiness. We absolutely cannot do that,” said Patricia Barron, head of military community and family policy at the Defense Department, in an interview with Military Times. “I think the department knew that before, but they really know it now.”

Barron, who was sworn in to the position in January of this year, said she’s very impressed with the work officials did at the beginning of the pandemic, “with the pivoting that had to happen in order to keep mission essential people at work and provide child care for their kids. What I also learned, with the child development programs, is that they are uniquely positioned for that kind of pivot.”

The requirements for health and wellness, sanitation, handwashing are all part of the culture of military child care programs, she said.

Overall, military child development centers are at about 75 percent of the capacity they were before COVID, and school-age care programs are at about 65 percent pre-COVID capacity, Barron said. Like those in the civilian community, many military child care facilities had to sharply reduce capacity.

As of April 21, all Army child development centers, school-aged care programs, and youth centers are open, but all are at reduced capacity, said Dee Geise, assistant deputy for quality of life for the Army. They generally are open at 50- to 75 percent of their pre-COVID capacity, but all are slowly getting more and more children back into their facilities, she said. As soon as installations return to normal operations, the child and youth programs will follow suit, she said, during a media roundtable with reporters.

“We have for many years stated that child and youth services are a force enabler. They decrease the stress between mission requirements and parental responsibilities. Over the past year that’s more than solidified the foundation of that talking point,” Geise said. For months, she said, “We had weekly reports going to the Secretary of the Army and the Secretary of Defense, because they knew it was a readiness issue, that our centers were directly impacting our readiness.”

During the pandemic, “we’ve lived our mission,” said Helen Roadarmel, chief of Army Child, Youth and School Services. “We found out how important it was to make sure soldiers have a safe place for their children while they were at work, especially important for all our mission essential and emergency personnel.”

Army senior leaders sent a letter April 21 to all child, youth and school services staff members and family child care providers, thanking them for their “unwavering commitment” to the Army, families and the children in their care, and acknowledging the 35th anniversary of the Month of the Military Child.

Meanwhile, Army officials have been taking steps to increase the capacity for child care, which has been an issue for military families for decades. That includes investing in two new large child development centers in Hawaii, and one at Fort Wainwright, Alaska. All three are in the beginning stages and will probably open in fiscal 2023. Each will have the capacity for 348 children. Another six will be in the works over the next five years.

To address staffing shortages, officials have increased salaries of staff members at child development centers; and implemented $1,000 recruitment incentives for family child care providers, as well as $1,000 retention payments for these family child care providers when they transfer to another installation.

Staff members of child and youth services and family child care providers know the importance of their work, but it’s been reinforced as children return to facilities as restrictions are eased. “It’s heartwarming to see these kids have all the smiles on their faces” as they come back to the youth programs, said Matthew Baptiste-Phillip, a child and youth program assistant at the Villaggio Youth Center in Vicenza, Italy. He was one of four employees involved in various child and youth services programs who participated in the roundtable.

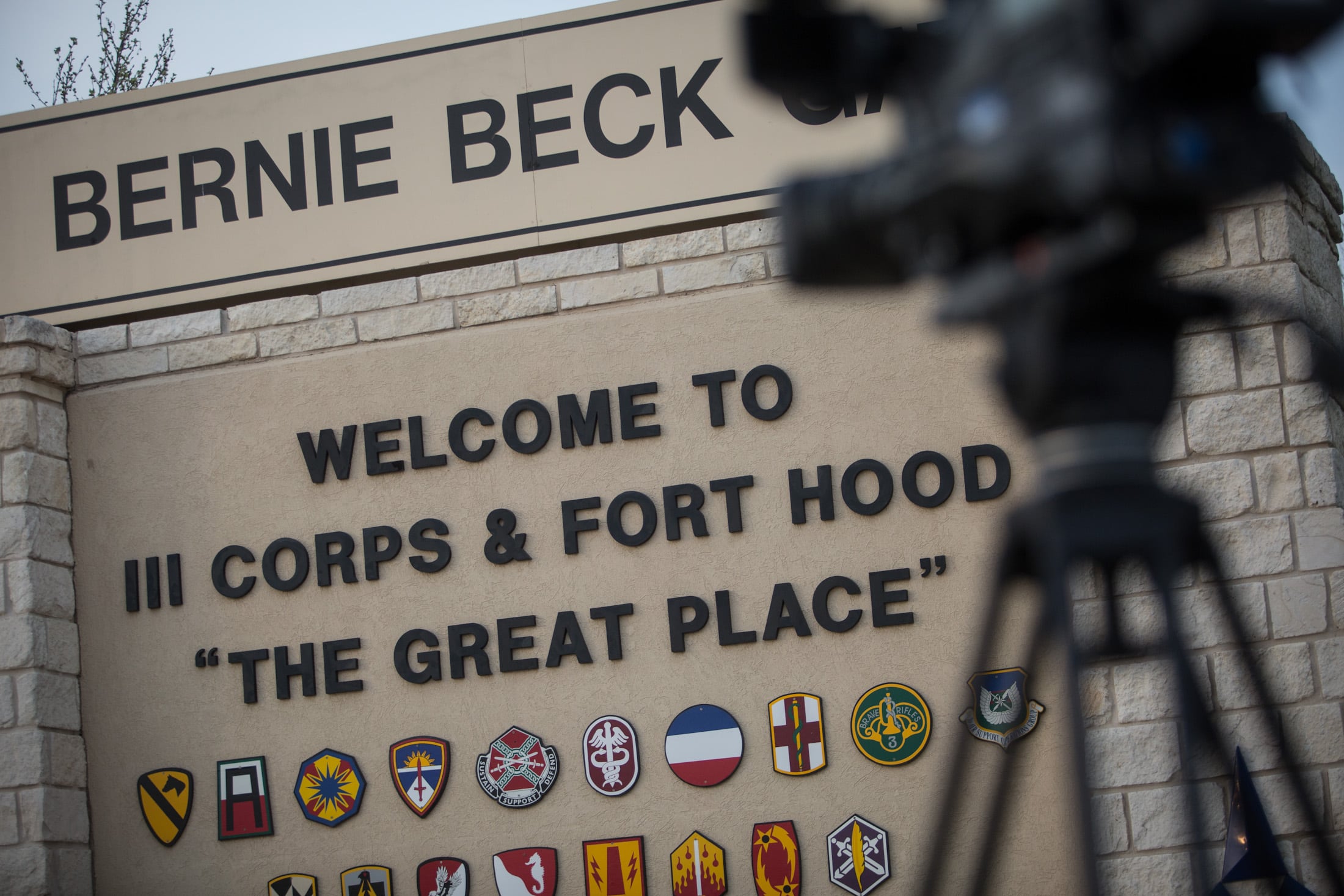

At Fort Hood, Texas, a lot of parents of teens were asking when the youth program would reopen, said Dan Schmidt, assistant director at Comanche Youth Center. “We heard from a lot of parents that for them, the most important thing was having a safe place for their youth to be every day after school. They don’t have to worry about where they are, or that they’re out there with hordes of other kids” who may not be practicing COVID-safe habits, he said. “More so, a lot of parents really appreciate the mentoring…… For that age group, developmentally, they need that peer-to-peer interaction. They need the structure from adults as they transition into adulthood. Losing that for nearly a year, and finally getting it back again, our parents were very appreciative.”

After being shut down for about a month and a half, the Imboden Child Development Center at Fort Jackson, S.C., reopened in June, 2020. “The staff was happy to be back, happy to serve the families. The children were happy to see us, and had a lot of stories to tell about what they did during shutdown,” said Christina Brown, a program director at the center, which serves the single and dual military drill sergeant population.

“Our parents are very thankful for the service,” said Brown. “We’re essential. If it weren’t for us, parents couldn’t fulfill their mission as drill sergeants. Drill sergeants work long and irregular hours. We’re a constant in these children’s lives,” she said, adding that they help provide consistent routines and nurturing care.

Amidst the fear and anxiety when the center reopened, she said, the center was reassuring parents about the safety of their children, especially since parents couldn’t enter the facility as part of COVID precautions limiting possible exposure. She also made sure to reassure her team about all the cleaning protocols taking place to ensure their safety. They made Facebook videos about how the precautions would work, and included virtual tours to show parents how they were keeping their children safe.

Like centers at other installations, parents drop off the child at the front door with a staff member, with enhanced health screening; parents meet the child at the door at the end of the day, with 100 percent ID check, she said.

Fort Jackson Child and Youth Services also created a pandemic page to keep team members connected, provide ongoing training and needed communication. “That’s turned into a retention and recruitment tool, because the team likes the cohesiveness that page brings,” Brown said.

That’s an Army-wide lesson, said Roadarmel. During the pandemic, the Army CYS has used the virtual environment a lot, to include conducting some inspections. “That virtual environment is something we’ll take a significant look at to see how we can use it better,” she said.

One child care option that never closed during the pandemic was Kaye Bremner’s family child care home at Fort Bliss, Texas. But she made significant adjustments: Parents and Bremner wear masks, and parents wash their hands before signing in or signing out their children. The parents remain in the home for a limited amount of time. There’s no more family-style peer dining: Bremner serves the children individually. Parents have supplied a pair of shoes that remain in Bremner’s home, and the children change into those when they arrive.

“My parents feel very comfortable leaving their kids,” Bremner said, noting there are few children, and the contact is limited.

Bremner, a family child care provider for 13 years, continues because of her love for children and the connections she makes with the parents and children. One of her former charges, a “very energetic, loving” child named Eugene, insisted that his mom bring him by to say “Hi,” so he could see “Miss Kaye,” if he wasn’t scheduled to be at her house that day, she said.

And although that family has PCSed, she still does video chats with Eugene and his mom.

Karen has covered military families, quality of life and consumer issues for Military Times for more than 30 years, and is co-author of a chapter on media coverage of military families in the book "A Battle Plan for Supporting Military Families." She previously worked for newspapers in Guam, Norfolk, Jacksonville, Fla., and Athens, Ga.