THE TRAGIC BETRAYAL OF AN ELITE COMMANDO UNIT

Editor’s note: This is the first in a five-part series.

OVERLAND PARK, Kan. — Fred Galvin was crying. He had welled up a few other times throughout the past three days, but now large tears spilled over his eyelids during an abrupt flashback to the St. Thomas More School playground and the rage he felt seeing two bullies pummel one of his classmates, an Asian kid named John Wong. Fred was a sixth grader at the time. “I remember how nobody else bothered to stick up for him,” he said.

In that moment, the battle-hardened Marine officer, now 45 and retired from the Corps, fought to stave off a memory that has pained him for decades. And then, just as suddenly as it had come on, the episode was over. He inhaled sharply, blotted his eyes dry and apologized. “It struck a nerve in me,” he recalled, “to see people gang up on a smaller student just because he looked and spoke different. I was sent to the principal’s office for defending him ... and drawing blood during the fight.”

Galvin has been in fights all his life. As a kid growing up in Kansas City, he challenged an abusive father because he was sick and tired of enduring the pain and destruction this man inflicted on his family. As a commander in combat, he battled for his very survival and that of his men, whether pulling the trigger against enemy forces or risking the wrath of superior officers to demand the resources his team required. And for the past eight years, Galvin has been on a lonely, emotional mission to restore honor to members of his elite commando unit who were wrongfully branded as war criminals during one of the most notorious criminal cases brought against U.S. service members during America’s 13-year war in Afghanistan.

They called themselves Task Force Violent. Recently declassified documents raise troubling questions about the military’s effort to send these Marines to prison. A legal tribunal ultimately cleared them of allegations they had mindlessly mowed down innocent Afghans, and exposed failures by senior leaders who sent them into the war zone without clear orders and without being sufficiently outfitted for combat. But the highly publicized ordeal left many of these men shattered — casualties, they say, of a politicized war and the sensational coverage by a media fed a story that sacrificed the truth from Day One, a truth only now coming to light.

READ PART 3: Marine commandos survived a nightmare. No one believed their story

READ PART 4: Embattled Marines came under fire — on the home front

READ PART 5: Now on the outside, betrayed Marines fight to recapture their stolen honor

A prior-enlisted sergeant, Galvin made history in February 2006 when, as a major, he was selected to lead Marine Special Operations Company Foxtrot for the first-ever overseas deployment of an operational unit from MARSOC, the Marine Corps force that carries out highly sensitive missions for U.S. Special Operations Command. It was a prestigious assignment for which Galvin was hand-selected based on his record of success leading Marines in the service’s specialized Force Reconnaissance community.

But the job would become a curse. On March 4, 2007, less than a month after arriving in country, 30 men with Fox Company’s direct-action platoon were riding in a six-vehicle convoy that was ambushed while patrolling in the Bati Kot district of Afghanistan’s Nangarhar province, a nefarious transfer point for suicide bombers and other extremists entering the country from Pakistan. Media reports about the incident seemed to surface before the smoke had cleared and the shell casings were collected. And it seemed to leave little doubt that the Marines went on a wild rampage, inflicting mass civilian casualties.

Within days, Fox Company was ordered out of the war zone under a cloud of shame. Galvin was stripped of command. Yet investigations into what happened in Bati Kot had only just begun.

Ten months later, in January 2008, the Marine Corps convened a rare court of inquiry at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, to determine whether there was sufficient credible evidence to warrant criminal charges, including negligent homicide, as recommended by an investigating officer. The proceedings lasted three weeks and took a heavy toll both physically and emotionally on the seven Marines most directly involved.

“It was a lonely, dark time,” Galvin recalled, still visibly unsettled by the experience. “I thought ‘we’d better get this right because we’re all in the same boat — and it’s headed straight to Leavenworth.‘” Fort Leavenworth is an Army post in eastern Kansas, less than an hour’s drive north of Galvin’s home. Some of the nicer officers’ quarters sit on a quiet bluff overlooking the Missouri River. And off to the north sits the U.S. military’s only maximum-security prison.

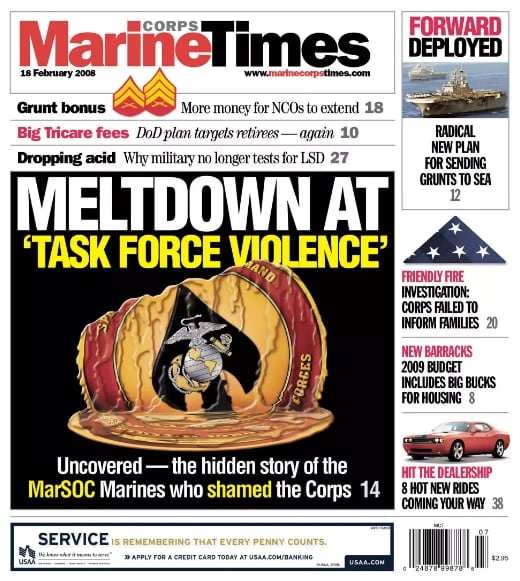

Media coverage from the court of inquiry was restricted by the military, with much of the testimony taking place behind closed doors to guard against the disclosure of classified information, officials explained at the time. As a consequence, an incomplete narrative would emerge. Marine Corps Times, for example, published a cover story in February 2008 boasting of hidden details about the “meltdown” within Task Force Violent and the “cowboys” who shamed the Corps — a characterization that has proven unfair and untrue.

In late May, just as the country was breaking for a long Memorial Day weekend, a three-star Marine general announced via press release his determination that Galvin and his men acted appropriately on the battlefield and in accordance with rules governing troops’ use of force. There would be no criminal charges for their actions in Bati Kot.

That story got out, but it didn’t stick. The complete account was never fully told or independently explored. And so, over time, many who remember the incident at all recall just two basic talking points: that MARSOC’s first deployment was a disaster and the Marines involved went to court suspected of murdering civilians. That’s become the unofficial footnote in history. And the Marines feel like they’ve never been fully vindicated.

“The big injury to Fred and his men is moral,” said Steve Morgan, a retired Marine lieutenant colonel and combat veteran who served as one of the three officers appointed to the court of inquiry. “It’s an injury to their souls.”

RUSH TO JUDGMENT

Buried in the court’s findings is evidence of the untold story. Morgan and his colleagues, Col. John O’Rourke and Col. Barton Sloat, would uncover that Fox Company was doomed to fail long before the Marines reached Afghanistan. Their findings are contained in a heavily redacted report, which was declassified and released to Galvin in late 2014. He provided a copy to Military Times along with newly disclosed transcripts from the court proceedings — nearly 2,000 pages in all. Another 1,500 pages of testimony remain classified along with related investigative materials.

The Marines were “superbly prepared for tactical employment,” the three officers determined. That was a testament to Galvin and his leadership team, Morgan told Military Times. But Fox Company was shipped out undermanned, under-equipped and “woefully underprepared for the political environment they encountered on the ground in Afghanistan,” he said.

The Marine Corps couldn’t figure out how to provide Galvin with the logistical and other support personnel he’d requested, so they deployed with just one mechanic to maintain the 45 vehicles in their motor pool. SOCOM, the report says, did not even inform the Marines where they were going until they had boarded the Navy ships that would carry them overseas, resulting in a frantic training effort focused on rules of engagement and cultural awareness specific to Afghanistan. Their primary mission — to train the Afghan security forces — wasn’t communicated to them for nearly another two weeks.

Life became more challenging for them in theater, the report says. Their camp, an empty facility aboard Jalalabad Airfield once occupied by French troops, had fallen into disrepair. There was fecal matter in their well water, Galvin said. Food and other basic supplies were tough to come by at first. Their lack of internal support personnel meant they were dependent on other units for help, and that caused a great deal of frustration for everyone. The Marines in MARSOC’s celebrated first combat deployment — who by their own admission were hungry to see some action — were essentially orphaned in the war zone, with no resources and no clear guidance, the court determined, and Fox Company routinely found itself at odds with the senior Army officers to whom they reported.

THE BATTLE SPACE: Fox Company arrived in Bagram, Afghanistan, in February 2007 and soon shipped out to Jalalabad Airfield in Nangarhar province.

The attack and subsequent gunbattle on March 4 marked the beginning of the end for Fox Company. The Marines left their base around 6 a.m. for an approved three-phase mission. They rolled east toward the Tora Bora mountains, still blanketed in snow and muck, driving through Bati Kot and to a key border crossing. They met briefly with an Army military police unit posted nearby before setting out once more to hunt for insertion points along the base of the mountains, spots with enough snow melt to enable future reconnaissance patrols.

Having found no promising leads, the convoy turned back toward Bati Kot where the Marines intended to meet with local elders and gain a better understanding of enemy activity in the region. As they approached, several military-age men lined the streets, the Marines recall. The bomber, who was driving a van packed with fuel, raced toward them and attempted to wedge himself between the first two humvees before pressing his detonator. Those closest to the blast are still haunted by the sound of the van’s tires screeching. Time froze for an instant, they say. And then there was fire, a massive ball of terror that erupted at least 100 feet into the air and briefly engulfed the convoy’s second humvee. Moments later, the sound of small arms fire rang out.

The Marines sent word to their operations center and higher headquarters that they had encountered enemy contact. Gun fire was coming at them from both sides of the road. Afghans who told investigators that they witnessed the attack would claim the Marines panicked after the explosion and opened fire on everything — and everyone — in sight. This dispute would set the stage for everything that befell Fox Company in the days and months to come. Some Afghans alleged the Marines left their vehicles and threatened local journalists who were taking photographs of the carnage. Some accused the Marines of appearing drunk. Both proved false, but not before those claims were publicized.

The ride back to base was tense. As the Marines hustled to get free of the danger, they hurled rocks and fired disabling shots at a few oncoming cars, a common warzone practice meant to keep the convoy moving and avoid being pinned in and attacked. Warning shots were fired to disperse a crowd and clear a path for the humvees — in accordance with protocol, Galvin said.

One of turret gunners who was exposed during the bomb blast sustained a wound to his arm. When they arrived at the airfield, he was taken for medical treatment. Despite the scare, the atmosphere was “jovial,” said one of the Marines on the patrol. “Everyone’s blood was pumping. We thought we’d done a good thing. We repelled the enemy. We won the gun battle. We protected the convoy.” The media was already reporting they had killed noncombatants. As Galvin and his leadership team compiled after action reports for higher headquarters, a TV in the chow hall was airing a report about the incident they’d just survived. The Marine couldn’t believe what he was seeing. “And I said: ‘Oh boy. What have I gotten myself into?’”

The military's investigation commenced almost immediately. But the "facts" accepted by investigators and subsequently presented to the court varied dramatically depending on the witness, the report concludes. For example, an Afghan man allegedly driving an SUV at which the Marines fired gave testimony so inconsistent that O'Rourke, Sloat and Morgan could not determine whether he was present during the attack or "lying," the report says.

The court's report says the investigating officer, Air Force Col. Patrick Pihana, attempted — unsuccessfully — to convince an Army explosives expert to reverse his determination that damage to their vehicles was caused by incoming small arms fire. After the soldier refused, the report says, the investigating officer elected not to include his statement in his final assessment of the incident, a decision the court's officers called "inappropriate" and may be due to the fact that the soldier's statement "did not support Col. Pihana's conclusion." Ultimately, Pihana recommended that four Marines be charged with negligent homicide. But to reach that conclusion, he had to "disregard the statements of every Marine on the convoy," the court determined.

O'Rourke, Sloat and Morgan questioned the propriety of Pihana and the commander who ordered the investigation, Army Maj. Gen. Frank Kearney, then the head of Special Operations Command Central. The court's final report says Pihana took an "unbalanced approach" to his investigation and thus reached "inaccurate conclusions." It says Pihana, Kearney's chief of staff, may have been "negatively influenced" by Kearney and others in the command — and that, above all, it was inappropriate for Kearney even to have assigned the investigation to his chief of staff, as doing so inherently raises questions about neutrality.

Fallout from the military's investigation of Fox Company spread beyond the Marines it implicated. Kearney, who retired from the Army in 2012 as a three-star general, wishes he never got involved. He, too, would be become the focus of an investigation, conducted by the Defense Department Inspector General, after a North Carolina congressman, Republican Rep. Walter Jones, accused Kearney of repeated misconduct in his handling of the case against Fox Company and another involving members of the Army's elite Green Berets.

This, too, surfaced in the press. Pihana would tell the IG's investigators that his boss never sought to influence his work. And although the inspector general concluded Kearney "acted reasonably and within his authority in both matters," the general now believes that such public scrutiny "ruined my career." Neither wished to revisit this case now, however.

Kearney told Military Times that he's "not interested in resurrecting the dead." He ordered an investigation at the Marine Corps' request, he said, indicating he believed that Marine leaders felt obligated in light of two other high-profile war-crime cases arising from the deaths of Iraqi civilians in Haditha and Hamdania. "If these Marines have heartburn," Kearney said, "it should be with the Marine Corps."

Pihana declined to be interviewed. "In recalling that event I remain convinced there is nothing substantial I could add, remove or change to the original inquiry," he said. "… I can understand the personal feelings involved but that would not change the thrust of the investigation" he said.

'MARINES DID NOT SNAP'

Few know the story about to unfold in this series because valid information about Fox Company's experience was suppressed, details that underscore the challenges American combat troops face on the modern battlefield. Galvin wants it all out in the open, so it's crystal clear the battle in Bati Kot was a "clean shoot," as he calls it. That his Marines never left their vehicles, that they did not lose control and that, as the court of inquiry concluded, they knew what they were shooting at and their use of force was warranted.

"We did not kill people who were not shooting at us," he said emphatically. "It is critically important that people understand we used precision fires, restraint. We were aiming at, and we killed, individuals who were directly shooting at us. There was no fog of war. Marines did not snap. These Marines were highly trained ... and did their job exactly how it was supposed to be performed."

The men most directly affected by this case share lingering fears of violent retaliation by enemies affiliated with those they encountered in Bati Kot. They've suffered health setbacks, including cancer diagnoses, which they link to the debilitating stress endured throughout their legal battle. Marriages collapsed. Some have battled depression and substance abuse. And although no one was thrown out of the military as a consequence of what happened to Fox Company, it has been exceedingly difficult for some to rebound professionally. "Google my name. I look like a murderer," said one of the Marines. "It'd be nice for people to know I didn't do anything wrong over there."

Throughout the war in Afghanistan, commanders, up to and including the commander in chief, spoke passionately about the necessity of limiting the loss of lives, limbs and property through reckless or otherwise excessive use of force. Yet what happened to the so-called MARSOC 7 — what was

allowed

to happen — represents a tragic hypocrisy, they say. How in the hell could senior military leaders demand of them such flawless objectivity and restraint on the battlefield only to come after them with such reckless ferocity?

In May 2007, Army Col. John Nicholson addressed the Pentagon press corps via satellite from Afghanistan. As commander of Task Force Spartan, he had oversight of the region to which Fox Company was assigned, including Bati Kot. Payments had been made to those claiming to have suffered a loss during the March 4 ambush, he said. What happened that day represented "a stain on our honor" and a "terrible, terrible mistake," he said. That's the story that stuck.

Attempts to reach Nicholson, now a three-star general in charge of NATO Land Command in Turkey, were unsuccessful, though a spokesman for the command acknowledged receiving several detailed questions from Military Times.

Military Times has spoken with several members of Fox Company, most of whom agreed to share their stories on the condition of anonymity as some still hold sensitive jobs within the Defense Department and elsewhere in the federal government. Others asked that their names not be used because they worry for their safety and that of their families. Each, however, expressed an intense desire to change conventional thinking about their history together, expose what they claim was irresponsible and unjust treatment, and ultimately make peace with the past.

"The looks and the jokes and people treating you like lepers. That's something our Marines still face because our side of the story — the full, complete story — is not out. It's still based on hearsay," Galvin said. "When I would move from one command to the next, I'd have Marines ask questions, which I couldn't believe they still had. 'How many civilians did you guys actually kill?'

"The seven of us named in that investigation saying our name was associated with negligent homicide carry around a burden. People continually bring up the incident as something that was shameful. That stigma is still widespread. Our Marines must begin the healing process, to finally let this go. And when they understand that our story has been told, I believe that is the next step to being able to forgive, forget and to move on with our lives."

This is that story.

Andrew deGrandpre is Military Times' digital news director. On Twitter: @adegrandpre