Over two dozen veterans can recount how chaplain Lt. Thomas Conway kept their hope alive as sharks swarmed the remains of the USS Indianapolis on July 30, 1945.

But a letter written in 1948 stating Conway went down with the sinking ship could be the reason behind the denial of a Navy Cross — a decision one Connecticut veterans organization wants to reverse.

"A journey of a thousand miles starts with one step, so we started," said committee secretary Robert Dorr.

The Navy denied last month the request from the Waterbury Veterans Memorial Committee to award Conway the Navy Cross, the second highest military decoration for valor for extraordinary heroism in combat. Conway was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart.

A bench erected by the committee in a city park commemorates two fallen chaplains from Waterbury — Conway, and Lt. Neil Doyle, who died on New Georgia Island in 1943 and, for his service, received the Distinguished Service Cross.

Father John Bevins, a retired Naval chaplain at the Basilica of the Immaculate Conception — the same parish where Conway was baptized — approached the 15-member committee in 2013 to have the same honor administered for his fallen parishioner.

Because the request was beyond the three-year limit in which a nomination may be submitted through appropriate channels, the committee went through Connecticut Sens. Chris Murphy and Richard Blumenthal to pass along the nomination to Navy Secretary Ray Mabus.

"We gathered together every recorded story, every magazine article, every newsletter ... and when you're looking through these newsletters, when they're talking about heroism, they're talking about Father Conway," Dorr told Military Times on Jan. 19.

It went beyond keeping the men together, Dorr said. The Indianapolis (CA-35), midway between Guam and Leyte Gulf, was hit by two torpedoes fired by the I-58 Japanese submarine. Conway floated from group to group of about 67 men called "the swimmers," praying, and reeling in sailors who began to drift away.

"We put together a compelling case," Dorr said of the nomination the committee submitted in September. The stepping stone, Dorr said, was looking at past chaplains who received such high honors, one being Cmdr. George Rentz.

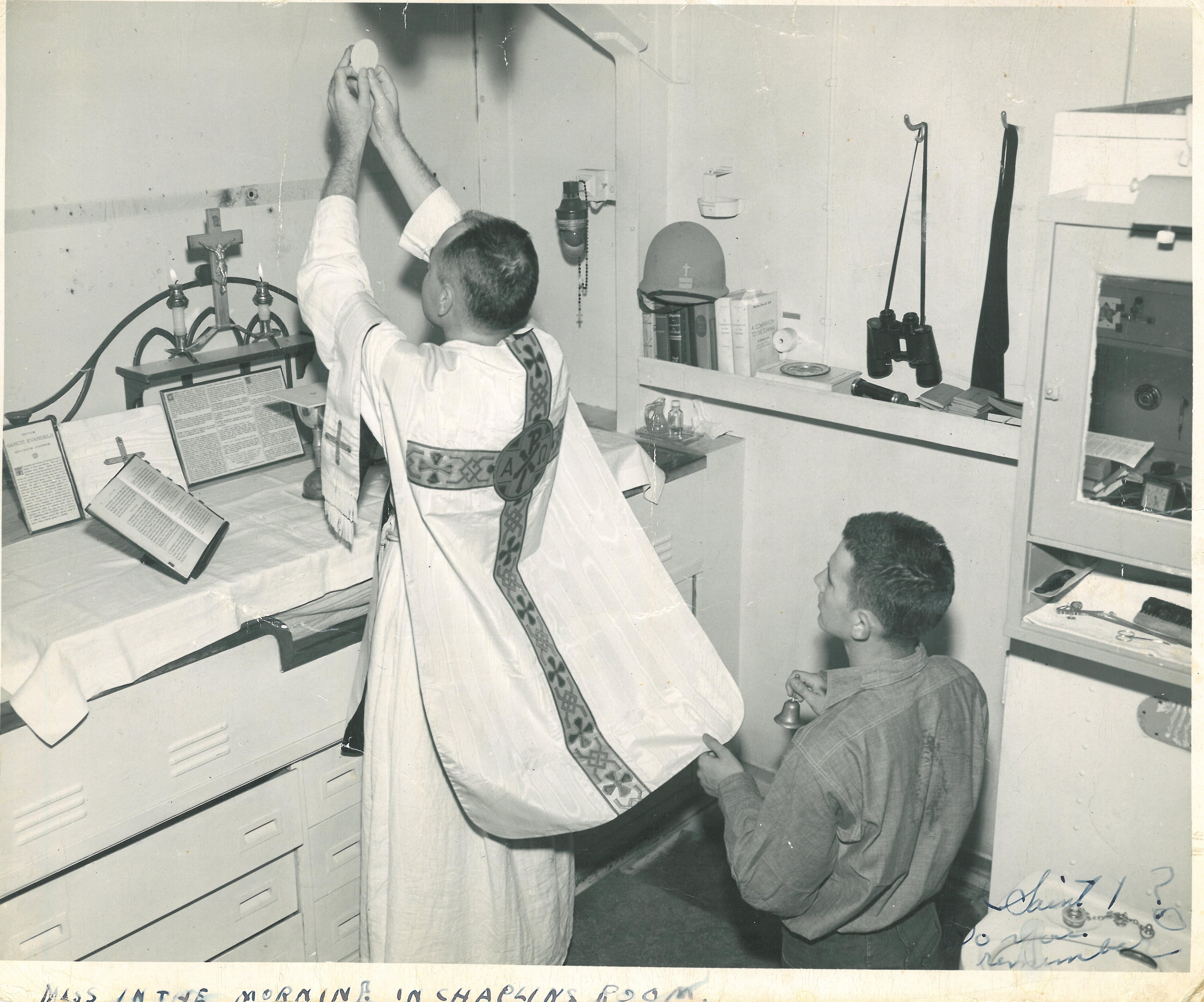

Lt. Thomas Conway says mass on the USS Indianapolis.

Photo Credit: Courtesy Robert Dorr

"There are considerable similarities," said Vietnam veteran Doug Sterner, a military historian and Military Times contributing editor. During the sinking of the USS Houston on Feb. 28, 1942, after a Japanese attack in the Pacific, Rentz sacrificed himself so sailors could climb aboard a pontoon, according to his Navy Cross citation provided by Sterner.

"We believe that [Conway's] service was equal to or greater than Cmdr. George Rentz," Dorr said.

However, Conway's heroic actions "never happened," Dorr said, because "the captain believed that Father Conway went down with the ship on July 30, and his letter was written in the official 1948 history of the Navy chaplains corps."

Dorr said evidence and testimony from survivors shows Conway died Aug. 2.

The letter was written by Indianapolis' commander, then-Capt. Charles McVay, who nominated a number of his officers and crew for personal decorations. McVay later went on to be court-martialed for putting his ship in harm's way for "failure to zigzag." But even after the widely publicized trial, McVay nominated others for awards — just not Conway.

"Your letter asserts that Captain McVay did not know of Lieutenant Conway's actions, and if he had known, he would have nominated his chaplain for the Navy Cross," R. Claussen, writing on behalf of Mabus, states in the denied request sent to Sen. Murphy's office. Claussen's title is not provided in the document.

"Based on our review of official records, it was not possible to establish whether Captain McVay knew any details of Chaplain Conway's actions," Claussen writes. "What is known is that Captain McVay did not personally witness all of the actions of every officer and Sailor he nominated for awards. Regulations only required that he know of the action, and had eyewitness testimony of others to substantiate them.

"We could find no evidence of any such claim having been made via official Navy channels, or recorded in official Navy documents. There appears to have been ample opportunity for those survivors to convey this information to Captain McVay."

"I find the lack of awards to Father Conway ... rather inequitable," Sterner said in an email to Military Times.

"I think in Conway's case, he probably was as much a victim to the embarrassment the Navy had with the debacle surrounding the Indianapolis sinking, and subsequent sadly handled inquiry, as he was to the sea."

"We've asked the Navy to revisit McVay's letter," Dorr said. "And in the response no one addressed that. They didn't say, 'Oh my God, you're right — there is an error in the official 1948 history.'"

All they cared about, Dorr said, was 10 U.S. Code 1130, "Consideration of proposals for decorations not previously submitted in timely fashion" regulations to submit the award, which are: the submission must be originated by a Chief Warrant Officer 2 or above; the commissioned officer was in the intended recipient's chain of command or had firsthand knowledge of the heroic act; and that the officer was senior to the intended recipient in either grade or position at the time of the act, according to the documents Murphy's office received from Claussen.

Because of the passage of time, this would preclude any enlisted men from making a recommendation for an award for Father Conway, Dorr said.

And whoever's left to tell Conway's story might not cut it, he said.

There are 37 survivors from the Indianapolis today, Dorr said. "They would like to see this — they're getting together for their last and final reunion July 23 in Indianapolis for the 70th anniversary of the sinking," he said.

The committee recently submitted a request to the Congressional Research Service through Murphy's office to look into any award recommendations that fall outside the scope of that regulation, Dorr said.

"We're delighted that Father Conway's story is being told," Dorr said, "and that the sacrifice of the men of the Indianapolis is again recognized."

"But if they're going to do it for somebody, why not Father Conway?"