Located on nearly 500 acres of picturesque land in the center of densely populated Brooklyn, New York, Green-Wood Cemetery is the final resting place of thousands of veterans.

Servicemembers from the Civil War through current conflicts are buried in the rolling hills and lush landscapes of this cultural landmark located in Brooklyn’s Greenwood Heights neighborhood, but Green-Wood officials don’t know just how many veterans have been interred on the grounds.

As one of the nation’s first rural cemeteries, Green-Wood has seen more than 575,000 interments since 1840, according to the cemetery’s full-time historian, Jeff Richman.

History of service has never been recorded in Green-Wood’s burial records.

The cemetery’s latest initiative seeks to identify the burial sites of every World War II veteran buried in Green-Wood. The project is the third in a series that has previously identified and honored Civil War and World War I veterans laid to rest in the cemetery.

It all started in 2002 after the rededication of Green-Wood’s Civil War monument inspired Richman to begin locating the gravestones of Civil War veterans.

“After the ceremony, I was speaking with a number of the reenactors there, and they said what an honor it was to be there. It occurred to me that we really should be looking for Civil War veterans,” said Richman. “I said at the time that we might find 500.”

Since Richman launched the cemetery’s ongoing Civil War project, more than 5,200 Civil War veterans have been identified.

In addition to identifying the burial sites of Civil War veterans, Richman wanted to recognize their service. Thanks to the help of volunteer writers and researchers, the cemetery’s website now contains a biography of each Civil War veteran identified.

Richman has also been working to secure headstones from the Department of Veterans Affairs for Civil War veterans in Green-Wood, approximately 40 percent of whom lie in unmarked graves.

He repeated the process in 2017 for Green-Wood’s WWI project, locating and writing biographies for about 200 veterans.

Now, as Richman shifts his focus toward identifying the graves of WWII veterans in the cemetery, things have changed: The stories of WWII veterans are much closer to their descendants than the stories of Civil War and WWI veterans.

“My only regret is that we didn’t do this sooner, but it really has been remarkable,” Richman told Military Times. “Certainly, when we did the Civil War and even the World War I projects, we didn’t have the ability to talk to people who had lived with these veterans and knew intimately their stories.”

Friends and family members of WWII veterans buried at Green-Wood can fill out a form on the cemetery’s website giving details of their loved one’s military service and personal life.

The responses so far have been astounding, according to Richman.

“We have heard from people whose ancestors landed in Normandy, fought in the Battle of the Bulge, liberated Dachau, and fought across North Africa and in the Pacific,” Richman said.

After receiving forms with details about a Green-Wood veteran, Richman and a team of volunteers follow up with background research, looking for census data online and contacting neighbors and family members to learn more.

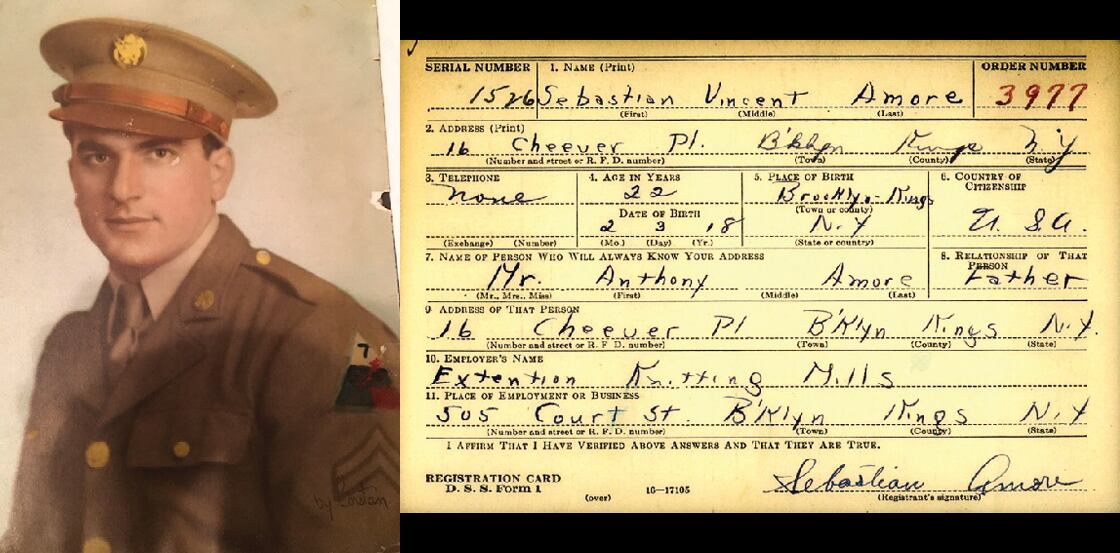

“What’s been remarkable also is the depth and wonder of the photographs people have been able to share of people in uniform during World War II,” said Richman.

Jessica Waverka started regularly taking her children to Green-Wood during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, when other parks in Brooklyn felt too crowded. Having lived in New York City for years, she had always appreciated the history held in the landmark cemetery.

“It’s a really beautiful and wonderful place to be. We would spend hours and hours walking and looking at the graves, reading their names, and thinking about the history,” she said.

When she heard about the WWII project, Waverka leapt at the opportunity to volunteer as a researcher.

“I’m so excited. I really can’t wait to contact people and capture those stories and pictures before they die out. We want to capture that,” said Waverka.

Although Richman has no idea how many how many veterans he expects to identify this time around, his preliminary research found more than 1,000 different obituaries citing both WWII and Green-Wood. The greatest challenge he’s encountered is finding accurate and accessible service records, since many were destroyed in the 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, Missouri.

The historian hopes to hold a commemoration for Green-Wood’s WWII project with contributing family members in attendance sometime in the next year, depending on the state of the pandemic.

If all goes well with the WWII project, Richman said the cemetery may begin similar initiatives to identify Korean and Vietnam War veterans in the future.

Harm Venhuizen is an editorial intern at Military Times. He is studying political science and philosophy at Calvin University, where he's also in the Army ROTC program.