This article first appeared on The War Horse, an award-winning nonprofit news organization educating the public on military service. Subscribe to its newsletter.

In the summer of 2015, active duty troops began to arrive in Bastrop, Texas, for a military training exercise. The exercise wasn’t much different from previous joint training exercises, except perhaps for its size. Over the course of two months, more than a thousand troops conducted training focused on operating in overseas combat environments.

It was different in one other respect, as well: Texas Gov. Greg Abbott had ordered the Texas State Guard to monitor the exercise. A civilian watchdog group formed to keep an eye on things, too. In D.C., Texas Sen. Ted Cruz reached out to the Pentagon ahead of the training — asking for reassurance that the exercise was, in fact, just an exercise.

Online, news of the training had quickly transformed into rumors and conspiracy theories. Operation Jade Helm, as the exercise was known, was a government ploy to seize people’s guns. The president was facilitating an invasion by Chinese troops. The exercise presaged an asteroid strike, which was going to wipe out civilization.

None of those things was true. At the end of Operation Jade Helm, the military went home. People still had their guns. No asteroid struck Earth. Three years later, in 2018, Michael Hayden, the former CIA director, said the tidal wave of theories around the operation had been the result of a Russian disinformation campaign.

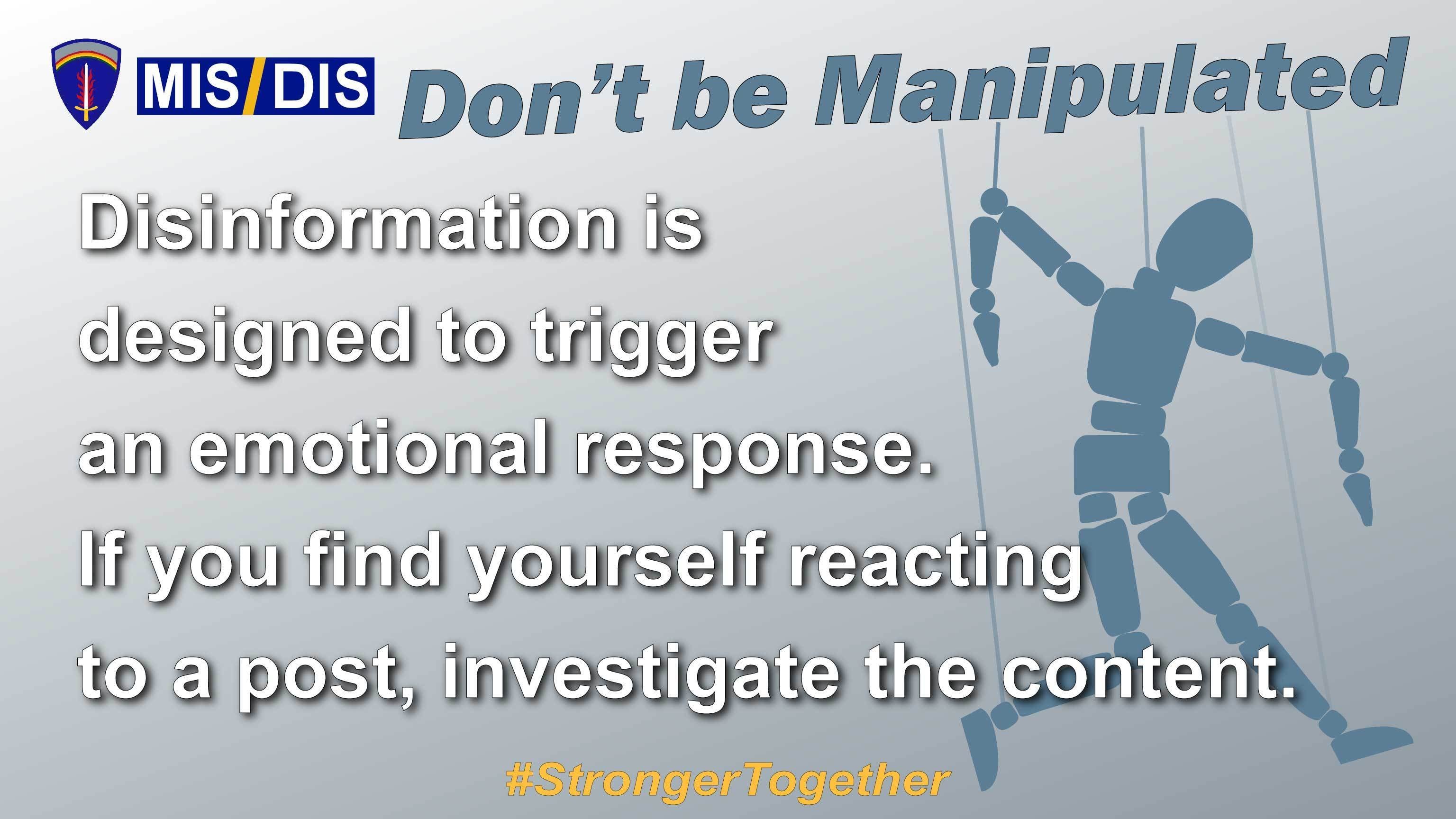

Over the past several years, disinformation, or the intentional deployment of false information for malicious ends, has emerged as a critical threat to public discourse and national unity. Events like Operation Jade Helm demonstrate just how quickly something ordinary can morph — online, and in people’s minds — into something extraordinary. The military community is not immune. In fact, veterans were among those who shared false rumors about Jade Helm.

While much of the conversation about social media and the military recently has focused on the specific concern around extremist radicalization, more garden-variety disinformation is also a growing issue. Disinformation can undermine critical thinking, sow confusion and suspicion, and threaten unit cohesion and force readiness. But the scope and unusual nature of the problem means it is difficult to protect troops.

“We prepare and train up for classic cyber threats,” says Peter W. Singer, author of the book ‘LikeWar: The Weaponization of Social Media’ and senior fellow at New America. “We don’t prepare and train up service members for its evil twin, which is the information warfare side.”

‘All warfare is based on deception’

Disinformation is nothing new. Way back in the 5th century B.C., the Chinese general and philosopher Sun Tzu wrote, “All warfare is based on deception.”

But the modern incarnation of deception — with its lightning-fast propagation on social media and the alarming ease with which people are weaponized, typically without their knowledge, to spread it — is new. The problem affects anyone who is online — and increasingly people offline as well, as ideas that form on the internet spill over into the physical world.

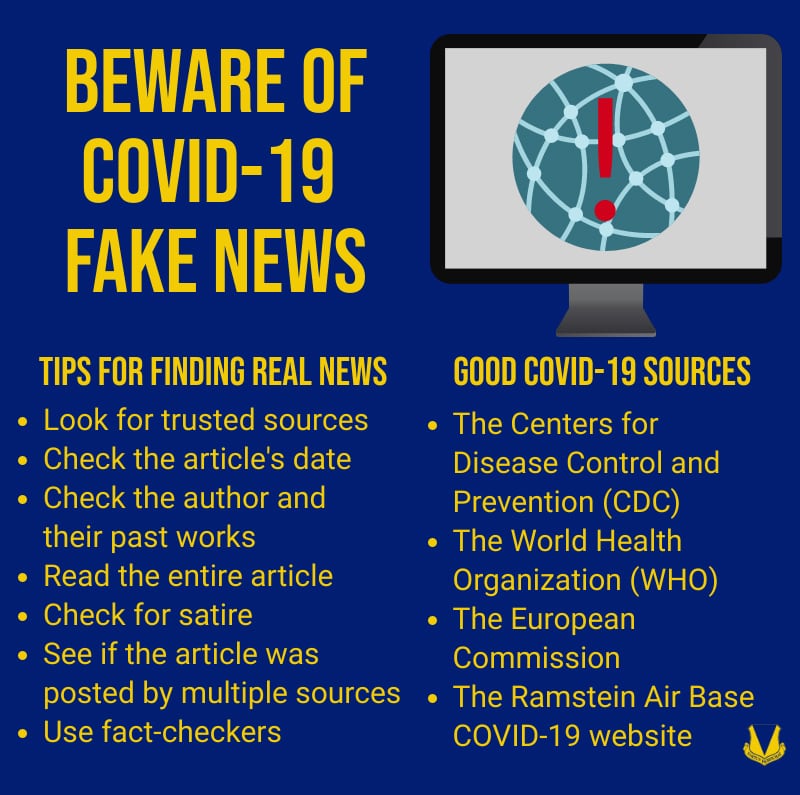

While disinformation (and its slightly more benign cousin, misinformation, which generally refers to false information) started to become a problem as social media exploded in popularity, it didn’t become clear the extent to which malicious actors, including foreign governments, intentionally spread false information until the 2016 presidential election. The COVID-19 pandemic then ignited what the World Health Organization deemed an “infodemic”: such an extraordinary amount of information, much of it false or misleading, that it becomes difficult for individuals to navigate, and, consequently, undermines public trust in authorities.

“People are deep in cognitive dissonance and institutional cynicism, and they just don’t believe they can trust anything — except for what’s coming from this one little echo chamber of belief, because they found a bunch of people who share that one specific set of beliefs,” says John Silva, a Marine veteran and the senior director of professional learning at the News Literacy Project, which teaches skills to counter misinformation.

Mis- and disinformation campaigns are effective because they feed into people’s beliefs and emotions. “We tap into people’s cynicism and […] other fears and anxieties,” he says. “And we have a lot of these bad actors out there that are influencing that and exploiting that.”

The problem can be particularly acute, he says, when beliefs we hold close are at stake — such as our health or service to our country.

“When we start to talk about these big things — like patriotism, like our respect and admiration for our troops and our veterans — there’s deep emotions there,” Silva says. “It’s really hard to have a critical conversation.”

In 2019, Vietnam Veterans of America released a report revealing that service members and veterans are at particular risk of disinformation campaigns. Its extensive two-year investigation found “persistent, pervasive, and coordinated online targeting of American service members, veterans, and their families by foreign entities who seek to disrupt American democracy.” The threats detailed in the report range from foreign actors creating Facebook groups purporting to represent veterans service organizations, to Russian-backed ads selling pro-U.S. military merchandise, to viral memes designed to encourage veterans to share with other veterans.

While sharing something on Facebook may feel benign, these campaigns grow with every repost. Given public trust in the military, posts by veterans and service members can lend a degree of credibility to an idea or narrative. But ultimately, disinformation campaigns are designed to exploit differences and encourage suspicions of people who disagree — which poses a real threat to unit cohesion, and ultimately to national security.

“We all need to be able to think critically. One of the demands of being in the Marine Corps is being able to make good decisions in stressful environments,” says Jennifer Giles, a Marine Corps major who has written about misinformation and military readiness. “You need to be able to protect your cognitive space.”

‘Certain things can make you a soft target’

The military has long recognized that force readiness depends on individual troop readiness. For instance, service members must maintain physical fitness: Lethality on the battlefield depends on it. More recently, troop training includes Anti-Terrorism Force Protection, or the idea that military members who may be targeted in terrorist attacks can take simple steps to minimize their susceptibility — things like varying routes to and from work and not wearing a uniform in public.

“Certain things like that, that can make you like a soft target,” says Jay Hagwood, a Coast Guard lieutenant commander who has organized media literacy training for Coast Guard members. The question, he says, is, “How do you harden that a little bit?”

The same question applies to online information. Simple steps, like understanding how disinformation campaigns work, verifying information before sharing, and improving critical thinking, can go a long way toward protecting service members. “What you’re a target for online, it can sometimes be just as damaging, in some ways,” Hagwood says.

But while the military has accepted and even embraced information warfare as a battlefield, the requirements for individual troop readiness haven’t developed commensurately. In part, that’s because the problem is so new. But misinformation is also a complex issue. It spans everything from sophisticated ideological campaigns originating in Russian troll farms to individual behavior on social media that can harm the military’s image, Singer says.

“The issue of the weaponization of social media is not only about extremism. It’s about Russian information warfare, to coronavirus vaccine disinformation, to Knucklehead on TikTok,” he says. “It’s not just about what you push out. It’s also about what you draw in, what you share. It’s about your entire behavior.”

Because of that pervasive, pernicious nature, there’s unlikely to be a single event that serves as a wake-up call for the military — like the worm Agent.btz that infected Pentagon computers in 2008, highlighting the need for force-wide cybersecurity readiness and ultimately paving the way to establish Cyber Command. It’s difficult to trace the divisiveness and suspicions caused by disinformation back to a particular origin.

And then there’s the inherently political nature of the problem. Misinformation about misinformation posits that the concept is itself a hoax — that it’s a made-up problem. Monitoring for misinformation can feel uncomfortably close to policing free speech.

“It feels like a third rail,” Singer says.

‘Disinformation is only effective if the recipient is vulnerable’

Last fall, Hagwood teamed up with the News Literacy Project to deliver training about misinformation to his Coast Guard unit in Los Angeles.

“It was an awareness objective,” Hagwood says. “Let’s learn the lexicon that is mis- and disinformation. Let’s learn what impostor content is. What’s false context? What’s fabricated content?”

The training was well-received, he says. Eventually, the admiral overseeing Coast Guard operations in California expanded it to all the units in his command.

“It was a lot of positive engagement,” Hagwood says. People came up to him afterward and told him how overwhelming the media environment felt. But a few days later, the Gateway Pundit, a far-right website known for publishing conspiracy theories, wrote about the training. The headline read, “Coast Guard Collaborate with Leftwing Hack to Indoctrinate Guardsmen on Leftist Propaganda in Forced 2-Hour Zoom Meeting Training.”

When Hagwood saw the article, he couldn’t help but think that it made an ideal case for the need to invest more in this sort of education. “It hits on everything that the training was designed to kind of illuminate for folks,” he says.

Silva, who conducted the training, says the episode highlighted why misinformation is such a difficult problem to confront. “I’ve tapped into something that they believe and I struck a nerve,” he says. “They’re going to lash out.”

But he and others who advocate for more training on misinformation argue there is nothing inherently political about learning to, as Giles puts it, “protect your cognitive space.”

“Media literacy is not about telling people what to think. It’s about thinking critically about the information you’re consuming,” she says.

“Education is the simplest thing, and the most immediate thing, and the most effective thing that we can do at our level for the individual. Because at the end of the day, mis- and disinformation is only effective if the recipient is vulnerable to it.”

This War Horse feature was reported by Sonner Kehrt, edited by Kelly Kennedy, fact-checked by Ben Kalin, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Abbie Bennett wrote the headlines.

Sonner Kehrt is an investigative reporter at The War Horse, where she covers the military and climate change, misinformation, and gender. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, WIRED magazine, Inside Climate News, The Verge, and other publications.