The American landing on Guadalcanal on Aug. 7, 1942 and subsequent seizure of the airbase they would name Henderson Field marked the first American offensive in the wake of the Dec. 7, 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. What followed was six months of savage fighting on land and a succession of naval engagements that cost 48 total warships between U.S. and Japanese forces.

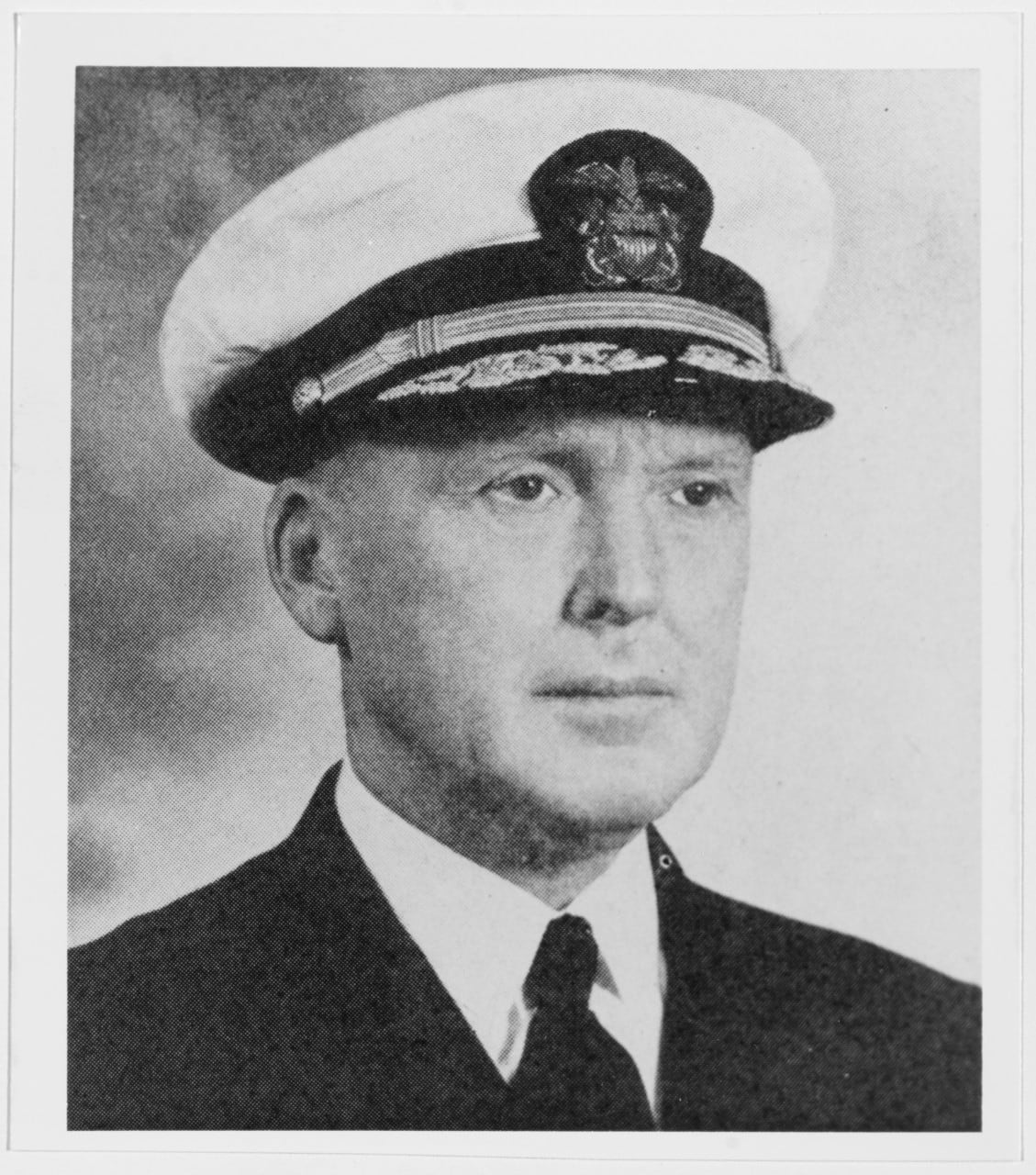

Among numerous naval heroes who emerged from both sides, Rear Adm. Norman Scott stood out for his role in two of the campaign’s most critical naval duels.

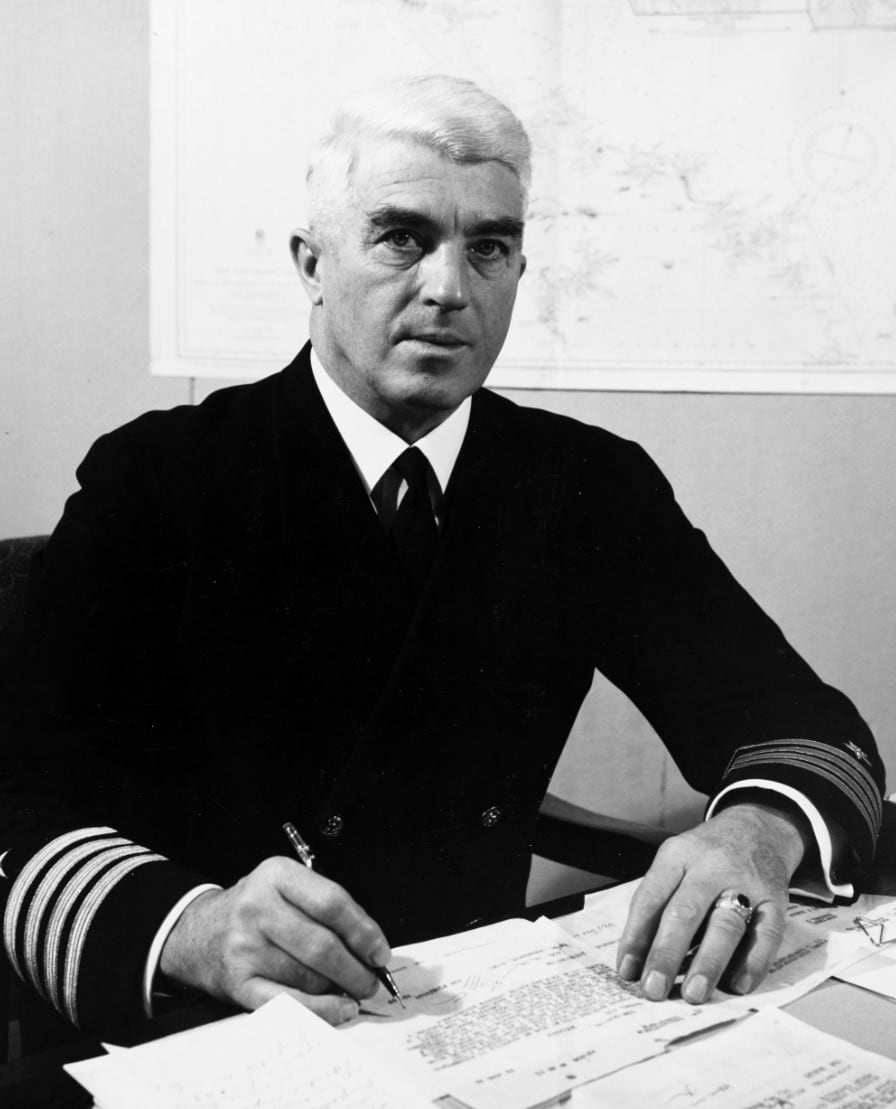

Born in Indianapolis, Indiana, on Aug. 10, 1889, Scott chose to leave his landlocked home for the sea and graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1911. That same year saw the graduation of Daniel Judson Callaghan, born in San Francisco on July 26, 1890, whose destiny would converge with Scott’s some 31 years later.

Scott first found action during World War I as the executive officer of USS Jacob Jones, which, on the night of Dec. 6, 1916, was torpedoed by the German submarine U-53. The Jacob Jones holds the distinction of becoming the first American destroyer loss in history. Of 110 crewmen, 64 lost their lives. Scott was among just five officers who survived.

After a succession of sea and land assignments during the 1920s-30s, Scott took command of the heavy cruiser Pensacola until just after the attack on Pearl Harbor, when he served at the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. He was promoted to rear admiral in May 1942, and ordered to the Pacific in June.

By that August he commanded San Juan, a specialized anti-aircraft light cruiser with 16 five-inch guns in twin turrets and the latest SG (screen grid) radar, designed to accompany and defend aircraft carriers such as Hornet and Enterprise.

On the night of Aug. 9, a Japanese force of cruisers and destroyers under Vice Adm. Gunichi Mikawa surprised an Allied cruiser squadron off Savo Island, sinking USS Astoria, Quincy and Vincennes and His Majesty’s Australian Ship Canberra.

It left the Allies demoralized. Fortunately for them, Mikawa departed rather than take full advantage of his success.

In September, Scott was placed in command of Task Force 64, or “Task Force Sugar,” charged with patrolling the southern approaches between Rennell Island and Lunga Point. On Oct. 7, he took position and, keen to get revenge for Savo, trained his men hard for the next several days. Finally, on Oct. 11, aircraft reported Japanese reinforcements coming down the island chain the Allies called “The Slot,” as well as an escort of cruisers and destroyers.

Flying his pennant from heavy cruiser San Francisco, Scott led heavy cruiser Salt Lake City, light cruisers Boise and Helena and five destroyers around the western end of Cape Esperance to cover entry into Savo Sound.

At 2325 hours Helena made contact with the enemy, but that was 15 minutes later than it should have — although (or perhaps because) it had the latest SG radar, it was stationed at the rear of Scott’s column. One of San Francisco’s floatplanes confirmed that enemy warships were coming directly toward the Americans, putting Scott in the enviable position of “crossing the T,” bringing more guns to bear.

Approaching was one of the victors at Savo Island, Rear Adm. Aritomo Goto’s Sentai (cruiser division) 6, comprising heavy cruisers Aoba, Furutaka and Kinugasa, plus two destroyers. As he closed in, Scott ordered “Left to course, 230 degrees,” but while most of his ships performed the right turn perfectly, three of his destroyers made wider turns that placed them behind Scott’s column and within range of the Japanese.

Amid the uncertainty, at 2346 Helena reported its radar contact and asked to open fire. Scott replied “Roger,” meaning he’d received the message, but Helena’s skipper interpreted it as “open fire.” And fire he did — joined by guns on both sides.

Four American destroyers were caught between the opposing columns and one, Duncan, was demolished by heavy cruiser Kinugasa and destroyer Hatsuyuki as well as some American shells.

It sank the next day with 50 of its 195 crewmen, though destroyer McCalla rescued the rest. Damaged were Salt Lake City, Boise and destroyer Farenholt. The Japanese suffered worse, with heavy cruiser Furutaka and destroyer Fubuki sunk, flagship Aoba badly damaged and Adm. Goto mortally wounded.

Goto’s sacrifice accomplished his primary mission, however. Unnoticed by the Allies, the troop transport ships he was protecting reached Guadalcanal unmolested, but Scott’s tactical success over Goto directly avenged Savo and, as the first major American cruiser victory in the Pacific, did much to restore Allied confidence.

There were, however, more sea battles to come.

On the night of Oct. 13, the Japanese battleships Kongo and Haruna pummeled Henderson Field, followed by a night bombardment by Chokai and Kinugasa on the 14th and another by heavy cruisers Myoko and Maya the following day. This was followed by a carrier confrontation off the Santa Cruz Islands on Oct. 26, in which the Americans lost the USS Hornet, but the Japanese again failed to follow through.

While Japan repaired or re-equipped their four carriers and the Americans hastily fixed up Enterprise, the Japanese gathered what they had left for the next bombardment: battleships Hiei and Kirishima, light cruiser Nagara and 14 destroyers, commanded by Rear Admiral Hiroaki Abe.

As this formidable fleet approached on the night of Nov. 12, three American cargo ships were en route to Guadalcanal, escorted by Scott aboard the anti-aircraft cruiser Atlanta alongside five destroyers.

Upon reaching their objective, Scott and his warships were ordered to join Task Group 67, led by Rear Adm. Daniel J. Callaghan from aboard his “hometown” flagship, San Francisco, with heavy cruiser Portland, light cruiser Helena and anti-aircraft cruiser Juneau, along with another three destroyers.

As they entered the combat zone the Americans took up a column like the one used so successfully at Cape Esperance, but also — once again — holding their three cruisers and two destroyers with SG radar at the rear. The Japanese battleships, on the other hand, had no radar at all. Add a rain squall to obscure both sides’ vision and their vanguards passed one another just after midnight on the ominous date of Friday the 13.

At 0124 Helena made first contact, but defective radar resulted in excessive reliance on talk between ships (TBS) until 0141, when destroyer Cushing made out enemy destroyers Yudachi and Harusame silhouetted in the starlight 3,000 yards away and turned left to bring its torpedoes into play.

Atlanta, next in line, also turned hard left. As his formation began falling apart, Adm. Callaghan signaled on the TBS, “What are you doing?”

“Avoiding our own destroyers,” Atlanta’s Capt. Samuel P. Jenkins reportedly responded.

With mounting confusion on both sides, at 0145 Callaghan signaled “Stand by to open fire!”

At 0150, however, a searchlight from Hiei pierced the darkness and fell on Atlanta, 5,000 meters away. Scott, true to form, ordered a full broadside, but all 12 of his shells fell 2,000 meters short. Thirty seconds later Hiei’s eight 14-inch guns, devastated Atlanta in one of the war’s most accurate salvos, killing Scott and all senior officers on the bridge save for a wounded Capt. Jenkins.

Although Atlanta was out of the fight, Hiei paid for its searchlight as destroyers Cushing, Laffey, Sterett and O’Bannon, finding themselves anywhere from 2,000 to a few hundred meters away, engaged the battleship in a desperate point blank duel to the death.

The Japanese destroyers were also embroiled in the fight, including Amatsukaze, which scored two torpedo hits on destroyer Barton that sank it with 90 percent of its crew.

Noticing Yudachi under fire from Juneau, Amatsukaze fired more torpedoes that drove the cruiser off with a broken back. Cushing attacked Hiei but was sunk by a broadside from destroyer Terutsuki.

Destroyer Laffey almost collided with Hiei, then raked its mast and bridge, killing Abe’s chief of staff, Capt. Masakane Suzuki, and wounding several officers, including Hiei’s Capt. Masao Nishida and Abe himself. Laffey was in turn hit by Hiei’s guns and sunk by a torpedo from Terutsuki. Sterett was badly damaged but managed to fight its way clear, while the “Lucky O” O’Bannon escaped serious destruction from the battleship.

At 0200 hours Abe called for a retirement, but Hiei was dead in the water after some 50 hits on its superstructure and having its internal communications knocked out. In contrast, Kirishima was grazed by a single eight-inch shell.

“We want the big ones,” Callaghan ordered, but some of San Francisco’s shells fell on Atlanta and Callaghan added to the confusion with a general order: “Cease firing own ships.”

Destroyer Akatsuki also scored torpedo hits on Atlanta, but was then caught between San Francisco, Portland and a destroyer whose combined fire sank it; the Americans later rescued 18 of its survivors.

Portland also fired at Inazuma and Ikazachi, but a torpedo from Yudachi jammed its rudder. Yudachi was in turn hit in the stern, probably by Aaron Ward, and ground to a halt.

Amatsukaze’s luck ran out when it was hit by Helena, retiring with 43 of its crew dead. Destroyer Monssen was sunk by Asagumo. San Francisco was also struck by Hiei and Kirishima, including a bridge hit that killed Callaghan, Capt. Cassin Young and other officers.

The next day revealed a grim tableau, but the carnage wasn’t over. San Francisco was still afloat and retiring with Juneau when a spread of torpedoes from Japanese submarine I-26 came at them, missing San Francisco but blowing up Juneau, leaving only 10 survivors of its 700-man crew, which included the five Sullivan brothers. Portland, still circling, came within range of the abandoned Yudachi and finished it off with a broadside.

To demonstrate the strategic outcome of the battle, however, Marine aircraft from a still-operational Henderson Field swarmed over Hiei, compelling Abe and surviving crewmen to relocate to the destroyer Yukikaze, leaving behind the first Japanese battleship loss since 1904. Ahead lay a second naval battle of Guadalcanal, which would seal the island’s ultimate fate and place the initiative in the Pacific in American hands for the duration.

Vice Adm. Abe and Captain Nishida were both subsequently “retired” from the navy for their lack of aggressiveness. Norman Scott and Daniel Callaghan were both posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.